Interview with Harriet Welty Rochefort, Author of Final Transgression

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

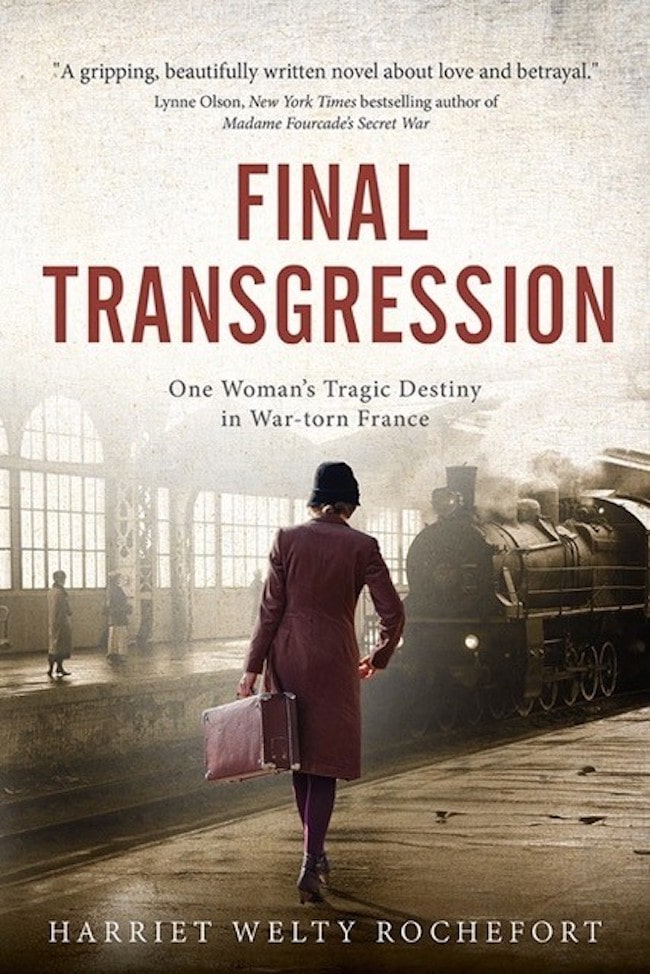

Fill in your credentials below.

Final Transgression: One Woman’s Tragic Destiny in War-Torn France is a compelling story rich in human complexities. Harriet Welty Rochefort’s fourth book—she is author of the best-selling French Toast, French Fried, and Joie de Vivre—this is her first novel, which was inspired by the sparse available details of a true story. Although readers know from the subtitle that this story will end badly, the suspense about how, and why, is effectively sustained until its inexorable, tragic conclusion. The author recently took the time to answer Janet Hulstrand’s questions about her new book for Bonjour Paris.

Janet Hulstrand: This story is set partly in Paris, and partly in Southwestern France, in 1944 toward the end of World War II, with flashbacks and flashforwards as well. Why did you choose to set the story where you did?

Harriet Welty Rochefort: I set the story in southwestern France because the events that inspired my story took place there in a little village in the Périgord. Readers who have visited the Périgord are familiar with its prehistoric caves and grottoes, its thousands of castles, and its renowned foie gras. When it comes to World War II history, though, they may not know that this largely rural area was a hotbed of fierce resistance activity that took place in the maquis, the name for the thick underbrush in the forests outside of small towns where freedom fighters—who were called maquisards—went into hiding to organise, and to train to fight the Germans.

Janet: When I attended your Zoom book launch, I was really interested in what you said about wanting to write a story that was about how “ordinary” people in France survived, or experienced, or lived through, the war. What did you mean by that, and why did you want to do that?

Harriet: I have read so many stories about World War II in which the hero or heroine is exceptional in some way; for example, either as a “bad” collaborator, or a “good” member of the Resistance. Most of the people in France were not that exceptional. They were simply concerned with getting from one day to the next, finding enough food for their families, and hoping not to get a bomb dropped on their homes. I thought it would be interesting to follow the trajectory of a woman whose only concern during the war was—ironic as it may seem, considering the times—to start a family.

Janet: What moved you to write this story? It’s based on a true story from your husband’s family that you were curious about, but afraid to ask about because you felt like you’d wandered into a taboo subject, right? That intrigues me. Why was it taboo, and how did you finally end up deciding to write this story?

Harriet: If a member of your family is accused of being a collaborationist, even if that has not been proved; and furthermore, if the person is killed, supposedly for that reason, it is a dolorous stain on those who remain. They never get over the person’s death, and they never get over the shame involved, even if it turns out that the motive for the assassination was the settling of a personal score, and not a proven case of collaboration. The story I tell was inspired by a true one in which this was the case; from what I turned up in my research, the person was not a collaborationist, but she was indeed regarded as a class enemy. That became clear when I went to the area and talked to people who had lived through that period, and knew the story. To give an idea of how long such taboos last, only two people in the village would talk to me about the events, and one of them swore me to silence. Fortunately, I was writing fiction: there were not enough details available to take any other path.

Janet: What is one of the most interesting or surprising things you learned in doing the research for this book?

Harriet: I think that, never having been occupied by a foreign power, we Americans have a hard time imagining the humiliation and burden of it: the humiliation at being overrun by a foreign enemy, the burden of having to live in extremely difficult and stressful conditions—kind of like the current coronavirus crisis, only much harder, and lasting for more than four years. I learned many things: that the French were ransomed by their occupiers, and had to pay the equivalent of today’s $150 million a DAY as “frais d’occupation” (occupation indemnity); that the Germans kept the French at starvation level, with a food ration that was half of what is normally required in terms of calories; and that people were cold. We all know about Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir huddling together in cafés, where they engaged in their intellectual pursuits; but they were also there, perhaps mainly there, as were a lot of other French people, because they were freezing, since the Germans controlled the coal industry. The cafés were warm, or at least a little warmer than their homes were. I learned that within the same family some people were for Marshal Pétain and the collaboration, and others for the Resistance; and that at the end of the war there was a period called the épuration sauvage, or “wild purges,” in which an estimated 10,000 French civilians were killed in acts of vigilante justice. These people were, rightly or wrongly, accused of collaboration, and they were killed either without benefit of a trial, or with a trial for which the outcome had been decided in advance.

Photo: Mat Reding, Unsplash

Janet: You’ve written three other books, and tons of journalism, but this is your first book of fiction. How long did it take you? What was the hardest thing about writing fiction? And what do you think many readers don’t understand about the process of writing fiction? Is it easier than writing nonfiction in some ways, and harder in others?

Harriet: I am basically a nonfiction writer, and for me writing fiction was akin to learning how to be a plumber, or a concert pianist. By that, I mean that writing fiction was entirely different from writing nonfiction, and I had to learn from the ground up. The hardest thing, I believe, were technical matters like dealing with point of view, that is, as the narrator, whose head are you in at any one time? Frankly, this first novel took me a long, long time to write—13 years from start to finish. During those years I turned out my third nonfiction book, so it wasn’t 13 years in which I did nothing else—but still!

Photo: Toa Heftiba, Unsplash

Developing the characters was a new exercise that I loved, and building a timetable for their actions during the 40-year span of the book required an Excel spreadsheet! Since this is an historical novel, I had to do extensive research on every aspect of the periods I was writing about, because while the characters are fictional, they move around in a real time period that is definitely not fiction: so it was up to me, as the author, to get the facts right. That is where my experience as a journalist was a huge help.

Janet: What do you think readers today can learn from this story that hopefully might help us better understand the past? And/or maybe even give us some ideas about how to learn not to repeat the mistakes of the past?

A court room. Photo: Sandra Dempsey, Unsplash

Harriet: Severine is judged severely by her own compatriots, who see her as a class enemy, and she does not benefit from a fair trial. There is always a danger when people think they hold morals and truth in their hands, and can disregard justice. If there is a lesson of the past not to repeat, it is to never give into vigilante justice and crowd rule. In the words of French writer François Mauriac: “Revenge disguised as justice is our most horrendous grimace.”

Purchase the book at your local independent bookstore (in Paris we recommend The Red Wheelbarrow and Shakespeare & Company), or on Amazon here.

Lead photo credit : Harriet Welty Rochefort, Author of Final Transgression. Photo: Harriet Welty Rochefort

More in author interviews, Resistance, WWII in Paris

REPLY