Time Travel to the Treehouses of Robinson

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

During my first trip to Paris, in the days when maps were the only option, I was unraveling the mysteries of the Metro, when I found that the RER Line B from Charles de Gaulle wound up at a station with the curiously incongruous English name of “Robinson.” Today my curiosity is sated, but the whimsical back-story of the suburb of Robinson might leave you wistfully wishing to turn back time.

In 1848 a Parisian innkeeper named Joseph Guesquin chanced upon a stand of huge chestnut trees near the village of Le Plessis-Piquet, situated at about 7 o’clock on the clockface of Paris. Inspired by the 1812 adventure Swiss Family Robinson, and Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Guesquin envisioned a restaurant in the trees’ leafy canopy, where wooden cabins could be linked by staircases and ramps.

In the 19th century, the banlieues of Paris were unsullied farmland, dotted with small villages. In the late 1850s, when railways started to replace the stage-coach as a means of transport, Parisians could easily escape the confines of the city. The countryside’s waterways lured boaters and picnickers to the popular al fresco guinguettes. Guinguettes were establishments traditionally located next to a river or canal, serving ample food and drinks, accompanied by dancing and the sound of lively music. Guinguettes ranged from rough and ready shanties with a few tables under the trees, to more elaborate establishments with full service restaurants with polished dance floors. Swings and see-saws, courts for boules and boats for hire were often within reach. Monet and Renoir immortalized the Parisians with their newfound sense of leisure in their vibrant Impressionist paintings.

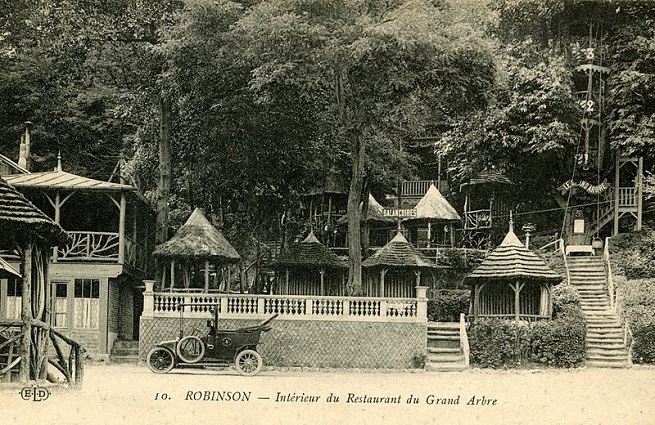

Le Grand Arbre, guinguette du Plessis-Robinson: 1921, BNF

However, instead of a watercourse, Guesquin built his dream guinguette in a grove of trees. In the branches of a 200-year-old chestnut in the rue de Malabry, he constructed three shady pavilions trellised with rambling roses. Perched in their dreamy tree houses, the customers were able to enjoy privacy in curtained quarters. Waiters would send up champagne and roast chicken in baskets hauled up by means of ropes and pulleys. Aloft in an enormous chestnut tree was the most romantic place to be in the outskirts of Paris. Les Guinguettes de Robinson was a unique and exotic summer adventure.

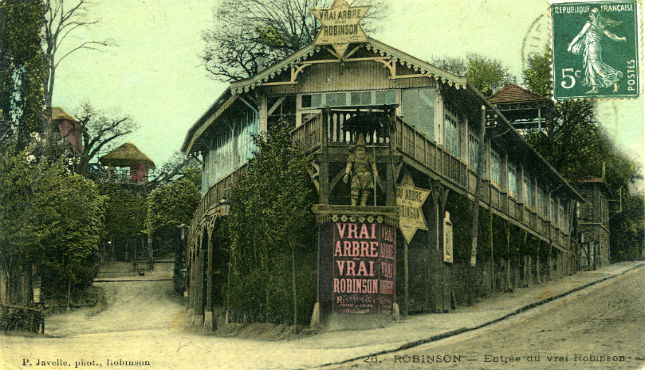

Guesquin’s first restaurant was named The Grand Robinson. It was instantly successful, but soon the time came to rename it the Vrai Arbre de Robinson or the True Tree of Robinson because Rue de Malabry was not lacking in giant chestnut trees where competitors could build their own tree house bistros. At the height of its fame there were more than 10 taverns and over 200 gazebos in the trees of Plessis, the most famous dining destinations being, in English, The True Tree, The Great Tree, The Tree of Rocks, The Great Saint-Éloi, The Fame of Fried Potatoes, The Hermitage, The Terrace Tree, and The Golden Snail.

Alexis Martin, author of the 1890 travel guide Les Etapes d’un Tourist en France described Robinson as “neither a village or a hamlet but one huge open air restaurant, quiet during the week but extraordinarily busy on Sundays. At Robinson there is feasting in all the trees, people drinking in all the terraces and beneath all the arbours there is dancing on the lawns. From Sceaux, from Fontenay, from all surrounding areas people arrive in charabancs, on horseback, by donkey, on foot, in long lines in serried ranks with whetted appetites and songs on their lips.” Another chronicler of the time, Louis Morin, remembered the singing, adding, “Little groups form who hardly know each other, but they know the song and that’s enough”

Guinguette du Plessis-Robinson, 1921: BNF

Louis Morin was a Parisian illustrator and caricaturist who published an account of his Parisian Sundays during the year 1898, while accompanied by his companion, Pompon. At his arrival in Robinson he was met by the famous donkeys. Author Craig Harline in his book Sunday: A History of the First Day from Babylonia to the Super Bowl, describes the bon-vivant Morin as a “frequent composer of frolicking nudes and slightly undressed figures,” who had no bone to pick with the other young men in attendance who couldn’t take their eyes off the young women’s dresses blowing butterfly-like in the wind. Apart from pretty girls on swings practicing their best Fragonard poses and the begrudging donkeys, there were scenic train rides up into the tree-top canopy and strolling musicians beneath the arbors.

Guinguette du Plessis-Robinson, 1921: BNF

Before long the village became such a popular Sunday destination that in 1909 the district was officially renamed Plessis-Robinson. The tree house village thrived as these photos from 1921 attest.

Russia’s Tsar and the Grand Duke Constantine, Spain’s Queen Isabella and King Alfonso XIII honored the Grand Robinson with their presence, and many other celebrities went there to dine. Louis Morin had the unlikely theory that the young ladies and gentlemen in attendance were “mostly the garçonnes and provincial girls landed in Paris for a few months who…are not affected by the preciousness of the neurosis of the young Parisians.” However one neurotic – Marcel Proust – visited Robinson, or at least his fictional Guermantes did!

Postcard showing Vrai Arbre, www.plessis-robinson.com/

In the years post World War Two, the spirit of the guinguette faded and the Robinson tree house taverns shuttered one after the other, slowly giving way to residential homes with solid footings. Then in 1966, another investor with his head in the clouds breathed life into the old pavilions. French pop sensation Johnny Hallyday bought Vrai Arbre Robinson and renovated it into a wild-West dream named Robinson Village. It was to be an American-style ranch with horses and a saloon; included were archery, rifle and pistol ranges. Somewhat safer amusements were bowling, pinball games and a disco. Hallyday’s cowboy time-machine became a commercial failure; however in October of ‘66 in the Tchoo-Tchoo Club, the disco attached to the complex, Hallyday presented his latest find from London, a hitherto unknown guitar player: Jimi Hendrix.

The last tree top bar, Le Grand Arbre closed in 1976. The façade of the Pavillon Lafontaine, at 34 rue de la Fontaine, was saved from demolition in the 1990s but looks very much from another place and time in its modern suburban setting. That and a small nest of planks are all that remain in the nearby trees. Some long-deserted pavilions on rue de Malabry are scheduled for redevelopment and may already be gone.

Disneyland Paris has a Swiss Family Tree House, no doubt a homogeneous attempt at amusement, but a far cry from the 19th century get-away where wine, romance and song were the order of the day. The trees in Plessis-Robinson have, alas, been left for the squirrels.

Darjeeling at French Wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Lead photo credit : [Promeneurs près de la guinguette Vrai Arbre du Plessis-]Robinson , 1921 : [photographie de presse] / [Agence Rol] [Promeneurs près de la guinguette Vrai Arbre du Plessis-]Robinson , 1921 : [photographie de presse] / [Agence Rol]

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY