The Smart Side of Paris: The Macabre History of Place Maubert

Just across the river from Notre Dame, there is a delightful view of the cathedral from a little park named Square René Viviani. At the end of springtime, you can stand in the square and frame the cathedral in an unforgettable arch of roses.

Then, you can turn around and find the oldest tree in Paris, a lovely 423-year-old Robinia tree, named for Jean Robin, a botanist who planted it during the reign of Henri IV in 1601.

Attached to the rear of the square is the 13th century church, Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, where you can listen to beautiful piano pieces played regularly. Or, if you are in the mood for books, Shakespeare and Company is about 20 feet away.

But for a little more history, you should exit the southeast corner of the square and walk about two blocks down rue Lagrange, where you will come to Place Maubert. It is a small, nondescript plaza that is little more than an intersection with a small fountain that hosts an open air market on Tuesday, Thursdays, and Saturdays.

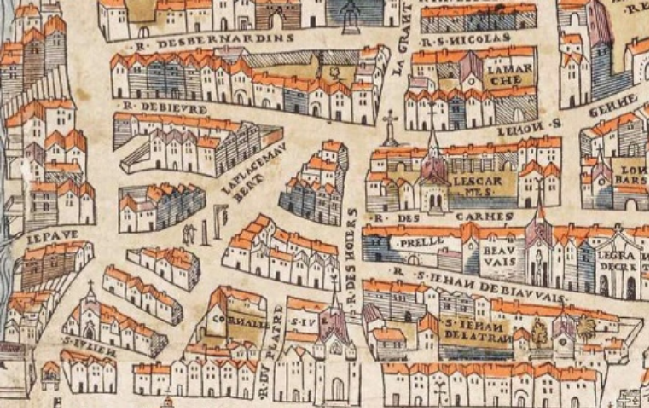

But Place Maubert has not always been so peaceful. In the map below from 1550, you can see the first few letters of La Grange at the top center and Place Maubert (LAPLACEMAV_BERT) in the center.

The Place Maubert on the Truschet et Hoyau Map (1550). Wikimedia commons

Looking closely, at the bottom of Place Maubert, you will see two human figures, one pointing, a post, and a hangman’s noose. Sadly, this was put to good use on those who were deemed to be blasphemers, heretics, and generally subversive types. Today, a fountain sits at the center of Place Maubert (see picture at top of article), having replaced the hangman’s noose; it also sits where a statue of its most famous victim died: Etienne Dolet.

Statue of Étienne Dolet, on the place Maubert. Agence Meurisse (1927) — Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public domain

Erected in 1898, that beautiful statue was taken down and melted during the German occupation of Paris.

Dolet alarmed royal authorities by writing and publishing works contrary to the Catholic faith. At the height of the kingdom’s ideological panic, King Francis I ordered Dolet’s works to be burned in front of Notre Dame Cathedral in 1544. Particularly threatening were books in French, which common people might read. Up in flames went his translation of the New Testament and a variety of other subversive and heretical books.

It might have ended there, but Dolet was, in one of the Medieval Inquisition’s favorite terms, “recalcitrant.” He just wouldn’t shut up.

And so, two years later, again accused of writing and publishing blasphemous books, Dolet was sentenced to die on his 37th birthday in 1546. He was carted (as part of the ritual of humiliation) to the plaza “where a gallows was to be erected in the most convenient and suitable place, around which was to be made a great fire, into which, after having been hung on the said gallows, his body was to be thrown with his books, and burnt to ashes.”

Book burning. Photo: LearningLark / Wikimedia commons

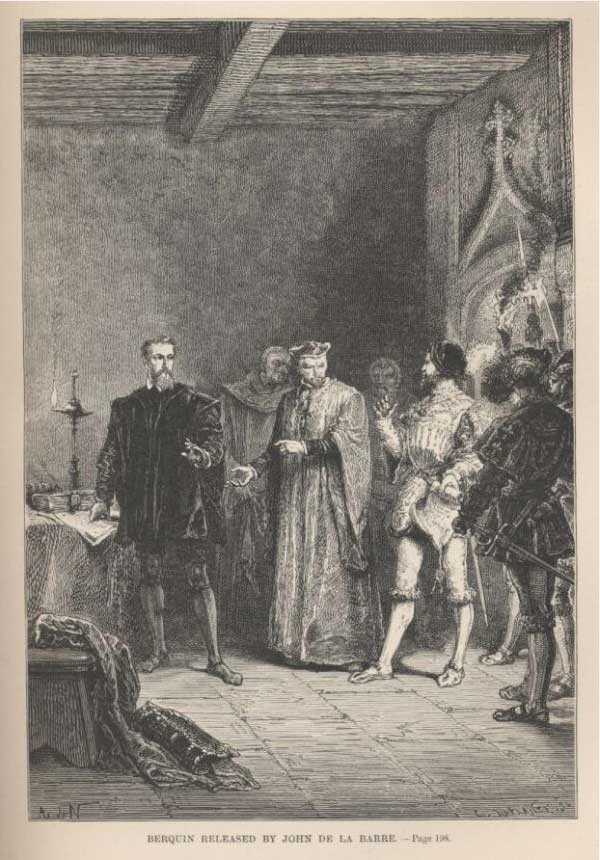

Dolet was not the first martyr to the cause of free thought and critical thinking to die at Place Maubert. In 1529, Louis de Berquin perished there for similar crimes. (Some sources say it was at the Place de Grève). Berquin took it into his head to study the Bible seriously. In doing so, he found that the doctrines that he accepted on faith did not accord with the scriptures that supposedly served as the source of those doctrines. Not having Montaigne’s subtlety, caution, or example, he was evidently too vocal about this disagreement, leading him to being condemned “to watch as his books were burned, to have his tongue pierced, and then to be imprisoned without reading material for life.” He was expected to recant his heretical ideas and submit unconditionally to the teachings of Rome, i.e., those contrary to ones that he had found in the Bible, however much in conflict he thought them to be. He refused. Consequently, he followed his beloved books to the flames the next day.

Engraving of Louis de Berquin (left) released from prison by John de la Barre. Public domain.

Numerous such stories could be recounted — and many more have been lost. The names run together: Alexandre d’Evreux, Antoine Augereau, Nicolas Clinet, Martin Lhomme… all names without meaning or statues today. Their list of punishments inspires a macabre ennui: “tongue cut out and burned alive,” “tongue pierced and burned alive,” “strangled and then burned,” “burned with his books,” etc. Some crimes are listed: heresy, printing forbidden books, or simply, “a printer,” from which we are to infer the heretical nature of the books he printed. The data could be catalogued under “martyrdom,” and we would all understand. But I think it more important to understand the symbolism behind the martyrdom.

The terrible executions at Place Maubert — and la Place de Grève (Hôtel de Ville today) and la Place Concorde — were symbolic spectacles. The ritualism uniting the executions — parading the victims to their death, carrying them in carts like animals, cutting out the tongue, using books to fodder the flames — was merciless medieval propaganda: morality plays in flesh and fire. Every measured step represented something. Heretics were carted like animals; tongues were pierced to symbolically censure disagreement; heretics burned in the fires of Hell. The executions symbolized the absolute necessity of conformity by showing where the path of deviation led. They scream, “This is what that means.” We watch from a safe historical distance as symbolism degrades to dogma.

The statue of Étienne Dolet (1509-1546) on the site of Place Maubert, photograph taken in 1899 by Eugène Atget. Public domain

Perhaps Etienne Dolet’s greatest scholarly contribution was to a field that required nuance rather than dogmatism: translation. His work, La manière de bien traduire, outlines rules for good translations from one language to another, the essence of which was to avoid literalism by deeply understanding the sense of the original and rendering it appropriately to the target language and culture. By insisting that true understanding meant allowing latitude of interpretation on the road to truth, and that language and culture demanded nuanced rather than dogmatic thinking, he helped pave the way for thinkers like Spinoza and Richard Simon to create their own heresies in the pursuit of truth. Their books were burned as well, although they escaped the flames.

Dolet’s 1898 biography, written to coincide with the installation of his memorial in Place Maubert, says that with that statue, France had finally paid its debt to a man who was “the honor of printing and of French letters.” It is my hope that the Patrimoine de France will restore the statue of Dolet to its place in Place Maubert, accompanied by a memorial to the martyrs who died there.

Lead photo credit : Place Maubert. Photo: John Eigenauer

More in Place Maubert, The smart side of Paris

REPLY