The Lost River of Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Some cities seem to reinvent themselves constantly — old buildings are torn down and replaced with shiny glass and steel skyscrapers almost weekly: Shanghai comes to mind, as an example. Other cities appear to be immemorial; they wear their history proudly and seem to be unchangeable. Many people would put Paris in that category. But Haussmannian Paris is only 170 years old and much of the rest of the city has undergone great changes more recently; it’s just that often it has happened away from the world famous museums, boulevards and monuments. Tucked away in the 13th and 5th arrondissements is one such change — a secret river that is completely hidden from view — but which was a bustling industrial artery a little over a century ago. And now, sections of it are coming back into use.

La Bièvre in Fresnes (Val de Marne). Photo credit: Mica/ Wikimedia Commons

Rising from an underground spring near the town of Guyancourt in the Île-de-France, the little river of La Bièvre flows northeast to enter modern Paris on the edge of the 13th arrondissement. No one is sure of the origin of its name: popular legend says it’s after the Gaulish word for “beaver,” although no bones or remains of beavers have ever been found. As far back as the 11th century its banks were covered with watermills. In the middle of the 12th century, the canons of the Abbaye Saint-Victor actually diverted it to improve the irrigation of their fields and increase the flow to their own flour mill. Streets such as Rue Moulin des Près hark back to these beginnings. The original course was named the bras mort or ‘dead arm’ and the new channel the bras vif or “living arm.” This is the river that was covered over in Paris. At one time frozen water from the river was stored underground during winter, to supply ice cream and sorbet makers in the summer – hence the origin of Glacière Métro Station. Not sure I would have wanted an ice cream frozen with river water!

The back of the Gobelins tapestry factory, where the river used to flow. Photo: Pat Hallam

Industry always characterized the Bièvre. In 1443 a young Flemish dyer arrived in Paris and set up his works on the riverbank. His name? Jean Gobelin. He would become renowned for his brilliant scarlet dye which, later, would be incorporated into the famous Gobelins tapestries that adorned royal palaces across Europe. His competitors were convinced the bright color was down to the clear waters of the Bièvre and rushed to set up their own dyeing works along the river.

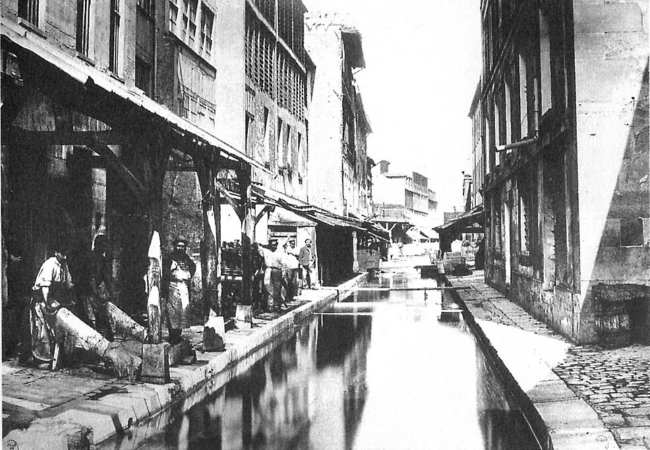

Not surprisingly, the water quickly lost its sparkle and purity and the river’s long descent into a polluted canal began. The process was intensified in 1672 when a royal ordinance decreed that all noxious industries had to move outside Paris. Dyeing works were joined by tanners, leatherworkers and laundries. By the middle of the 19th century, the whole stretch of the river alongside the present Rue Croulebarbe and the surrounding area was little more than an open sewer. Photographs of the time show the street and surrounding area full of mills, dyeworks and tanneries, the buildings butting right up to the riverside.

However, a series of disease outbreaks were blamed on the polluted water and from the time of Haussmann onwards, the river was progressively culverted until, by 1912, it was completely covered over.

Chateau de la Reine Blanche. Photo: Pat Hallam

Traces of the river and its former industries can still be found in the Rue Croulebarbe and Rue Berbier-des-Mets in the 13th arrondissement. The course of the bras vif is marked out in brass medallions set into the road. The back of the Gobelins tapestry works still dominates the Rue Berbier-des-Mets, and the Rue des Gobelins – clearly named after its most famous manufacturer – was earlier known as Rue de la Bièvre.

A pleasant detour: Walk around the corner to Rue Gustave Geoffroy and you will come across a small complex of some of the oldest surviving buildings in Paris. The Chateau de la Reine Blanche (Castle of the White Queen) was originally built by Blanche, daughter of King Louis IX, around 1300. Nothing survives of it but the Gobelins family replaced it around 1500 with their family home and adopted the original name. Two buildings were built at numbers 17 and 19 – one facing the street and another at the bottom of a passage. You can enter the courtyard and see the white square turrets of the Gobelins’ chateau. The Gobelins family moved out in the 17th century and the chateau was occupied by Benedictine monks for a time, then by a sheet-maker and a tannery. One of the old workshops still survives in the courtyard.

Remaining workshop in the courtyard of the Chateau de la Reine Blanche. Photo: Pat Hallam

By the way, a little further out, in the Butte aux Cailles district, it is still possible to drink spring water from an artesian well and the street art around here is by a local group calling themselves “Lézarts de la Bièvre.”

View this post on Instagram

From the Square René le Gall, formerly known as L’Île des Singes (Monkey Island), the Bièvre used to flow under the 5th arrondissement before finally joining the Seine between the Jardin des Plantes and the Gare d’Austerlitz. Its primary purpose these days is as a stormwater drain. (Before the river enters Paris, the water is diverted into a treatment plant.) Yet now that the river has been cleaned in the suburbs, and part of it opened in Gentilly and Arcueil with pleasant riverside parks, the hope is to open parts in Paris that are now buried underground. The built-up environment makes it difficult, but there is a project to bring the river back to life.

Medallion in the road locating the course of the river. Photo: Pat Hallam

During the 2022 city elections, the Green party campaigned to uncover stretches of the Bièvre and as part of the coalition deal, the Socialists agreed to a feasibility study. Paris is a very densely populated city with relatively few green spaces and the vast majority of buildings lack air conditioning. This makes it especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change and in recent years summer heatwaves have emphasized the “heat sink” effect of built-up areas. The heat-absorbing effect of tarmac and concrete can raise the temperature inside Paris by as much as 8°C compared to the suburbs. The municipality is already introducing extra tree-planting to counteract this effect, and uncovering the Bièvre would introduce “îlots de fraîcheur” (cool islands). It has been demonstrated that spots like this can significantly lower the surrounding temperature.

The first two stretches most likely to be opened up are on the edge of the 13th arrondissement where the river enters the city under the Parc Kellerman, and in the Rue Croulebarbe area next to Square René Le Gall where it flows directly beneath the road. It is hoped that they will be open by 2026, the end of the council’s current term of office. It is unlikely the re-exposed river will ever regain the purity it enjoyed in the days of the Saint Victor monks, but nevertheless it will be a welcome addition to Paris’s outdoor spaces.

Map of La Bièvre. Photo: Ccmpg / Wikimedia Commons

Lead photo credit : Tanneries along the Bièvre, late 19th-century. Photo: Charles Marville/ Wikimedia Commons

More in Bièvre

REPLY