The Caribbean Beauty Who Scandalized Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Tucked away on a minor path in the heart of Père-Lachaise Cemetery, a simple tomb bears witness to the life of a remarkable woman who once was the toast of Napoleonic and Restoration society. A woman who scandalized the bourgeoisie with her numerous lovers and habit of wearing virtually see-through dresses, and was probably a spy.

Her name was Fortunée Hamelin, the mixed-race daughter of Jean Lormier Lagrave, a wealthy sugar plantation owner on the island of Santo Domingo in the Caribbean. A certain mystery surrounds her birth. Officially she was the legitimate daughter of Lormier Lagrave; nevertheless a girl with the same name was baptized on the same day in the same church — only this child was born two years earlier in 1776. It seems likely that Lormier Lagrave’s legitimate daughter died in babyhood and was “replaced” by this older child, the illegitimate daughter of Lormier Lagrave and a freed slave. Fortunée’s physical appearance certainly indicated such a possibility.

Boulevards of Paris including Rue d’Hauteville, Public Domain

Her father sent her to Paris to find a good husband and Fortunée was married off to a very rich and ambitious cousin who was rising swiftly up post-Revolutionary society. Aged 14, it was not a love match but it did allow her to escape her mother’s influence. Two years later she inherited a small townhouse in the Rue d’Hauteville after her father’s premature death. Coinciding as it did with the fall of Robespierre and the end of the bloodiest chapter of the Revolution, this legacy and her husband’s fortune enabled Fortunée to begin her conquest of Paris society.

It is hard to over-estimate the difference which Robespierre’s death made to daily life. Almost overnight, the Terror evaporated. Once again, people could live without fear of being sent to the guillotine. In some ways it was as if the Revolution had never happened: the laws prohibiting extravagant dress were repealed, private carriages reappeared on the streets, and domestic servants were allowed once more.

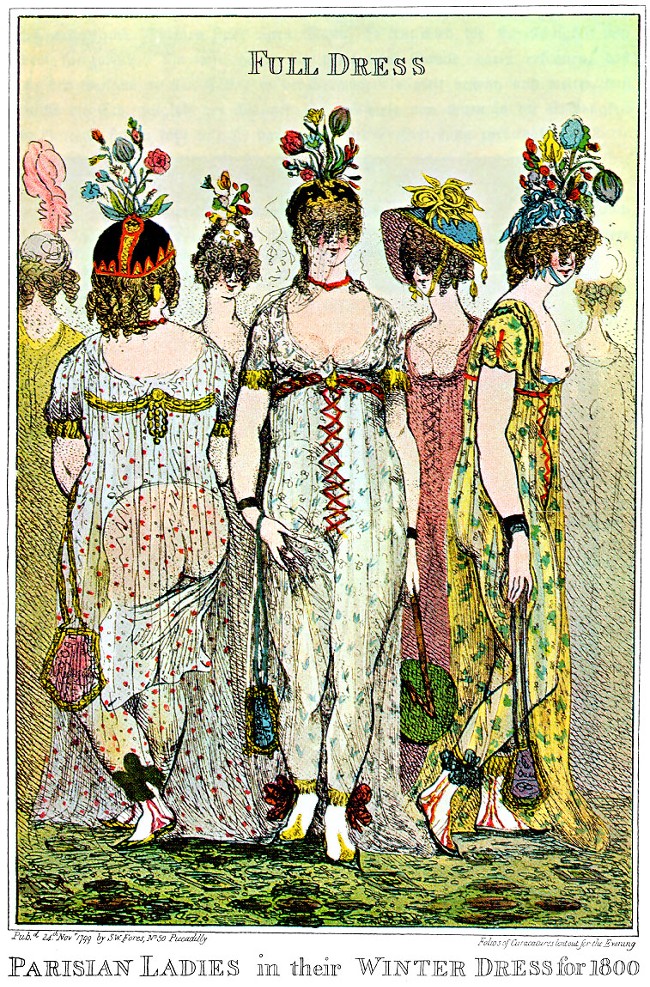

The Merveilleuses in their winter outfits for 1799. English caricature by Isaac Cruikshank. Public domain

Fortunée took full advantage of these new freedoms. In particular she spearheaded the Directoire fashion for the flimsiest, most low-cut barely-there gowns inspired by the Ancient Greeks, often accessorized with huge bouffant hairstyles. Fortunée’s thick curls were heaven-sent for these.

This new generation of Bright Young Things were known as the Merveilleuses and Incroyables. They were either aristocrats returning from exile, or aping their former extreme fashions, and they were regularly satirized for their appearance. It was a reputation Fortunée delighted in. On one occasion she was mobbed while descending from a carriage on the Champs Elysées: she was wearing a transparent chiffon gauze gown over flesh-colored underclothes and slit to the thigh. It was held in place by a simple sash and exposed her breasts. Not leaving much to the imagination! Her husband was so mortified he whisked her off to Italy. A fateful decision as Fortunée met Joséphine de Beauharnais (later Bonaparte) there and thus began a long friendship between the two outsider women from the Antilles (Joséphine came from Martinique).

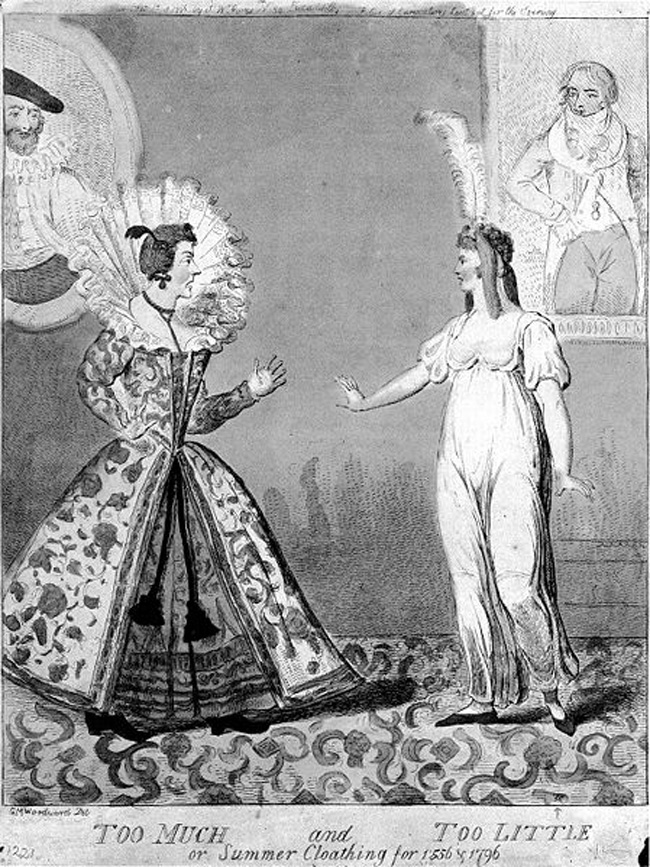

A satirical 1796 contrast between old 16th-century and cutting-edge Directoire clothing style. Isaac Cruikshank, Public Domain

Back in Paris, Fortunée and Joséphine, along with Juliette Récamier and Thérèse Tallien, ruled high society with their salons and political connections. Having given birth to two children, Fortunée decided she had done her conjugal duty and started collecting lovers. She was not a conventional beauty, being darker-skinned and well-built compared to the norm. But her exotic looks immediately drew attention, and her sparkling personality and passion for dancing made her a favorite guest at balls across the city.

By the way, her house, which was sold in 1798, became the Hôtel Bourrienne. It is now the headquarters of a very upmarket shirt company which has restored the interior, making it a rare example of interior design from the Directory and Consulate period. It’s not open to the public but if you can get into the courtyard you can look inside one of the rooms that has been faithfully restored.

Hôtel de Bourrienne. Credit: Naxos0203, Wikimedia Commons

Today, Fortunée would be a regular in celebrity magazines for her outrageous behavior. She was called “la plus grande polissonne en France,” a “polissonne” referring to a scandalously risqué woman. One of her most famous lovers was an insubordinate Hussar named François-Fournier Sarlovèze who achieved notoriety for challenging a rival to a duel 14 times. His life was fictionalized in Joseph Conrad’s novel The Duel and Ridley Scott’s film The Duelists. A few years later she allowed into her bed the extremely rich banker Julien Gabriel Ouvrand. He appears to have been completely smitten with Fortunée, putting his large fortune at her disposal as well as his contacts in Paris society. But Fortunée did possess a moral code: Ouvrand was a corrupt banker and she refused to touch his money. Eventually, Fortunée’s husband could stand the scandals and gossip no longer and their marriage collapsed in 1804.

Through Joséphine she met Napoleon and was immediately bowled over by his charisma and political ideas. This was a hero worship that endured right through Napoleon’s exiles and beyond his death. Napoleon was equally captivated by her looks, her witty conversation and intelligence. Interestingly, considering how Fortunée collected lovers like other women collected jewelry, Joséphine never seemed to feel threatened by her affections for Napoleon and their friendship endured for many years.

Napoléon offering flowers to Joséphine. by Jean-Louis-Victor Viger du Vigneau (1819-1879) © E.R.L./SIPA

That’s not to say that Napoleon didn’t find Fortunée useful. Her art for seductive conversation picked up all sorts of useful information from the businessmen, politicians and military attachés who attended her salon, and she willingly passed this back to the emperor, who recompensed her to the tune of a healthy 2,000 francs a month. Napoleon’s First Minister Talleyrand was another recipient of Fortunée’s information-gathering.

Fortunée was appalled by the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1814 and continued to work for Napoleon as a secret agent throughout his exile on Elba. However, when he was finally banished to St Helena after the Battle of Waterloo, the authorities clamped down and she was promptly exiled to Brussels. However, after two boring years, pressure from influential friends secured her return to France.

Battlefield at Waterloo. Credit: William Sadler, Public Domain

Never one to hide her sympathies, Fortunée always wore two gold naploéon coins as a pendant. She moved back to her town house in Rue Blanche in the newly-fashionable suburb of Nouvelle Athènes (now in the 9th arrondissement), where she opened another salon. This became a melting pot of former Bonapartists, royalists and those who were disillusioned by the Restoration. Fortunée had a gift for keeping in touch with people and regular visitors included the aging politicians Talleyrand and Chateaubriand, whom she had known since the early days of the Empire.

Unsurprisingly, the authorities kept her under surveillance and her movements were closely monitored. At the same time, the police realized she had access to sources of information beyond their official reach and put her on the informants’ payroll for a number of years under the pseudonym “Madame Deschamps.”

The rue de Clichy today. Photo credit: Mbzt/ Wikimedia commons

During these years, Fortunée moved into property development and bought a house in the Rue de Clichy as well as parcels of land all over the new, fashionable neighborhood around the Arc de Triomphe (to the extent that the area was nicknamed Quartier de l’Avenue Fortunée). As she aged she inevitably lost the gamine slimness of her youth but was still coquettish and striking. Her circle of admirers changed to include a new generation of artists and writers, including Balzac and Victor Hugo, who was a neighbor for a while.

She detested the “bourgeois” (and in her eyes philistine) King Louis Philippe. She kept in touch with the Bonapartes in exile and rejoiced when Louis Napoleon returned to power in 1848. Sadly, her last years were marred by illness, legal disputes over property, the sudden death of her only daughter, and the gradual passing away of her friends and lovers.

On July 31, 1830, Louis-Philippe leaves the Palais-Royal © Horace Vernet. Public Domain

Fortunée died of apoplexy in April 1851. She was initially buried in Montmartre Cemetery but was soon moved to her daughter’s grave in Père-Lachaise. There she lies alongside her ex-husband Romain Hamelin and son Edouard. No religious symbol adorns the modest tomb and the marble inscription is almost effaced. And Fortunée herself has slipped into the footnotes of history, upstaged by the better-known Beauharnais and Récamier. But in her time she was the talk of Paris society and epitomized the hedonistic years following the French Revolution.

Lead photo credit : Portrait of Madame Hamelin, née Fortunée Lormier-Lagrave by Andrea Appiani, Musée Carnavalet, Public Domain

More in Directoire Fashion, Fortunée Hamelin, history, women in history, Women who shaped Paris

REPLY