Picasso and the Women’s Prison of Saint-Lazare

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

To coincide with the Musée d’Orsay’s hugely popular exhibition dedicated to Pablo Picasso’s blue and rose periods, we dive into the great artist’s time in Paris…

In 1901, Picasso’s Blue Period coincided with the death of his close friend, Carlos Casagemas, and his first visit to the Saint-Lazare women’s prison near Montmartre. Profoundly affected by Casagemas’ suicide, Picasso began painting in blue.

The two young artists from Catalan had first met in the Café Els Quatre Gats in Barcelona in 1899 and moved to Montmartre in 1901. Casagemas, an innovative and highly talented artist, fell in love with Germaine Gargallo. Their ‘affair’– ill-fated from the start since Casagemas was impotent and Gargallo fairly liberal with her favors– was to end tragically.

L’Hippodrome de Montmartre. Public domain

Picasso was in Barcelona when in the Café de L’Hippodrome on the Boulevard de Clichy, Casagemas in a fit of jealousy, drew his gun on Gargallo. Believing he’d wounded her, Casagemas shot himself in the head. He died the next day in the hospital Bichat.

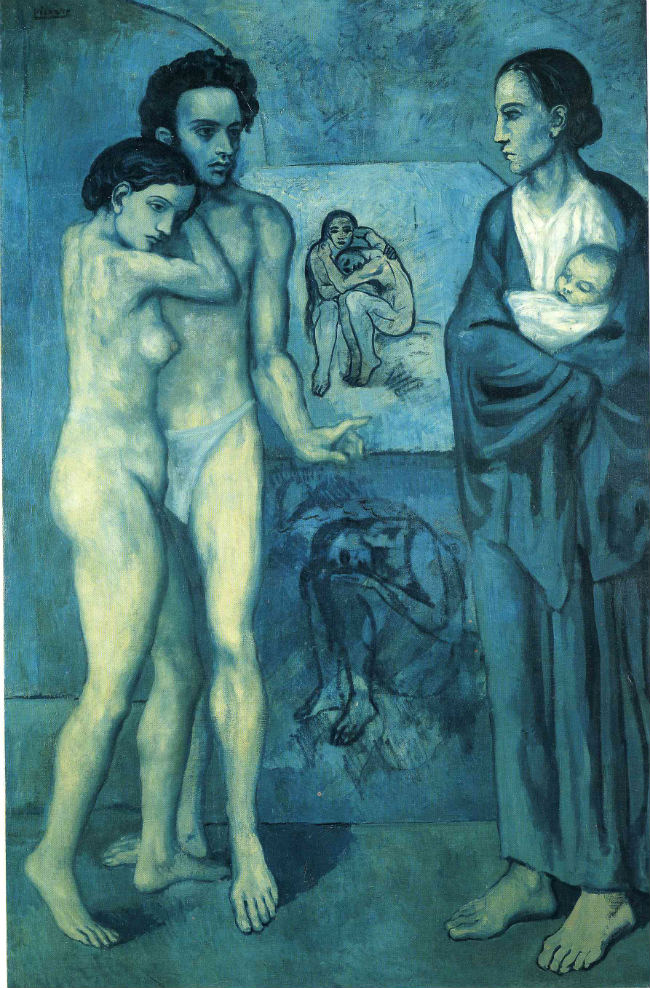

On his return from Barcelona, Picasso moved into Casagemas’s studio on the Boulevard de Clichy. Many of the paintings on display in the Musée d’Orsay’s Picasso: Bleu et Rose exhibition depict Casagemas: “La Vie” and “Death of Casagemas”– a stark portrait of Casagemas’s head in death.

Pablo Picasso, La Vie, 1903, Cleveland Museum of Art. Public domain.

Traumatized by the death of his friend, the consequent sadness Picasso suffered in the aftermath revealed itself in this new approach to his painting.

The women’s prison in Saint Lazare presented Picasso with scenes of deprivation, depression and helplessness that captured his feelings in a real and tangible way and initiated a series of paintings on motherhood which he continued to paint on his return to Barcelona.

The Saint-Lazare prison was situated near Montmartre and mainly housed prostitutes, some with their children. Women who had venereal disease were singled out with white bonnets. Picasso’s “Woman with Bonnet” (1901), “Two Sisters,” “Mother and Child” (1902), and “Melancholy Woman” were all inspired by his visits to the prison. The paintings embodying the loneliness of these desperate, mistreated women. Picasso transformed the short white caps to El Greco style hoods and their striped black and white clothes into long, blue tunics.

The Saint-Lazare Prison in 1912. Photo: Agence Rol/ Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public domain

Conditions at the Saint-Lazare prison were grim and it was commonly considered to be the only answer to prostitution and the epidemic of venereal disease, in particular, syphilis, rampaging throughout France. The blame for the increase in cases of these diseases was firmly placed on the rise of the Brasseries à Femme in the second half of the 19th century. Although of course, there was always an abundance of street walkers, the licensed brothels, which were kept under weekly medical supervision and more or less free of venereal diseases, were closed by the authorities on the slightest complaint and licenses hard to come by. So the Brasseries à Femme, cafés where men could be served drinks and more by pretty barmaids, were an instant success.

Pablo Picasso in 1908. Anonymous. Public domain.

Until the 1860s, alcohol and sex had never been served together, and men who were averse to entering a brothel, now had the perfect, legitimate outlet for finding a prostitute in the guise of a barmaid. By the end of the 19th century, the brasseries employed between 1500 and 2000 waitresses. Though similar in appearance to any other café, the brasseries had separate rooms for private encounters. The waitresses, often working a 12-hour day, were paid to encourage the clients to drink more, sit with them and sell their services. However they were not under any medical controls and cases of venereal disease increased ten-fold. (It was not hard to find the attractions of being a barmaid. A good barmaid could make in a day what a factory worker made in a month.)

There were many protests at the rise of venereal diseases, “the scourge of France.” The only treatment– often unsuccessful– was by mercury. Finally a law was passed allowing only the female members of the brasserie owner to work behind the bar putting an end to waitresses in all these establishments. Outrage was also expressed for the poor wives of husbands who had infected them by visiting a prostitute. Needless to say that in Victorian times, the husband was never blamed…

Easy to see that the Saint-Lazare prison was never short of prisoners.

The prison started life as a leper colony in the 12th century and was then ceded to St Paul de Vincent and the Congregation Mission in 1632. It wasn’t until 1793 during the Reign of Terror that the building became a prison and turned into a woman’s prison in the early 19th century. In 1836 the new infirmary was added. Between 1871-1903, 725,000 women were arrested and imprisoned in Saint-Lazare– whether they were of age or not.

The Death of Casagemas, Pablo Picasso. Photo: Marilyn Brouwer

For the prostitutes, there was no court hearing, instead they were condemned without appeal by a Chef de Bureau of the Prefecture de Police. They were condemned to imprisonment from three days to two months in a separate section of the prison.

Overseen by one of the Sisters of the Order of Marie-Joseph, the prisoners were issued with prison suits and housed in dormitories containing 80 or more beds. Prayers were compulsory and when sewing in the workrooms, complete silence was demanded.

Set apart from the prostitutes were nursing mothers, mothers with a child under four years old, and pregnant women. The convicted mothers were kept apart from the prévenues– women who were simply accused, not yet convicted– but in both incidences, a homeless woman could be incarcerated alongside a hardened criminal guilty of infanticide or murder. Likewise little girls of 10 or 12 were kept together with habitual criminals.

Musée d’Orsay. Photo: Bonjour Paris

Less likely to be found in Saint-Lazare prison were those known as les gigolettes. These wily prostitutes, almost always worked for a pimp, ran with hardened thieves and garrotters on the outskirts of Paris (La Villette, Belleville, or Clignancourt). Without conscience or morals, la gigolette was guilty of luring her clients into an ambush where her pimp and his accomplices would rob and beat up, or worse, the unfortunate victim. Unlike the majority of prostitutes who found themselves in Saint-Lazare prison, for la gigolette it was a temporary hardship. She would leave unreformed but more heartless and vengeful than before.

La gigolette would not find herself in one of Picasso’s paintings.

Picasso’s paintings of the prostitutes in Saint-Lazare prison are imbued with a deep sadness and compassion for their misery and loneliness. The haunting blue of these canvases are as much a testament to the prostitutes’ unhappiness as his own.

Saint-Lazare prison was demolished in 1935. Until recently, a hospital was installed . in the remaining buildings.

Picasso: Bleu et Rose is at the Musée d’Orsay until January 6th, 2019.

1 rue de la Légion d’Honneur, 75007. Tel: +33 (0)1 40 49 48 14. Closed Mondays. Open from 9:30 am to 6 pm, with a late closure on Thursdays at 9:45 pm.

Lead photo credit : Picasso at the Orsay Museum. Photo: Marilyn Brouwer

More in picasso