Madame d’Aulnoy: Mother of the Fairy Tale

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

When it comes to fairy tales, Charles Perrault is best remembered as the author of some of the most enduring stories for children. He penned works including Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, Puss in Boots, and his collection of Mother Goose stories.

What isn’t remembered is that the “mother” of the fairy tale was the scandalous, upper class, female writer Madame d’Aulnoy. D’Aulnoy was celebrated throughout Paris for the imaginative stories she told at her salon. When her stories were published in book form, not only did she coin the term “fairy tale,” but her storylines were the first to feature “Prince Charmant” or Prince Charming. She authored stories with wonderfully whimsical titles such as Princess Mayblossom, The Bee and the Orange Tree, and The Benevolent Frog. Unfortunately, Madame d’Aulnoy’s status as “queen of the fairies” was eclipsed as Perrault, the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Anderson became the genre’s leading men.

Portrait of Madame d’Aulnoy by Pierre-François Basan. Public domain.

Once upon a time, circa 1651, the originator of the fairy tale was born as Marie-Catherine le Jumel de Barneville. She was raised in a wealthy family in Barneville-la-Bertran, near Honfleur in Normandy, where her love of folk stories was likely fostered by the nannies and housemaids that surrounded her. At the age of 13, Marie-Catherine was a hyperbolic and humorous child, wishing plague, pestilence, and broken bones on anyone that didn’t appreciate her favorite books. At this point, the girl would have benefited from the intervention of a good fairy, because by the age of 15, Marie-Catherine was married off to Baron d’Aulnoy, a man 30 years older. By the age of 19, she had four pregnancies, which resulted in two daughters. Two more d’Aulnoy daughters were born, but well after the Baron disinherited Marie-Catherine. Disinherited? Why? Well…

The May-December marriage was troubled from the start by her husband’s gambling and his heart-breaking infidelity. In 1669, Marie-Catherine, her mother, and two male accomplices, lovers, perhaps – perilously plotted to implicate Baron d’Aulnoy with treason, in particular lèse-majesté. Apparently, talking trash about the monarch was a crime punishable by death and the accused baron was jailed at the Bastille. Nevertheless, the foursome was not rid of him; the plot backfired. The baron was released and the accomplices were charged with calumny, aka slander (apparently another crime punishable by death) and executed.

The Bastille Prison in 1715. Rigaud, 18th century – Bibliotheque Nationale de France. Public domain

There are many versions of what happened next to Marie-Catherine. Some scholars agree that she and her mother escaped to England and Spain, where they may have contritely spied for the government of Louis XIV. There are also documents proving that her ex-husband consigned her to a convent on the Rue Mouffetard for bad behavior. Perchance her fairy godmother finally waved her magic wand; from this point it remains a mystery how she was able to support herself, and who fathered her youngest daughters.

It’s confirmed that around 1685 Madam d’Aulnoy bought a house on rue Saint-Benoît, just to the north of today’s famous restaurants, Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots. She was accepted into Parisian high society and in turn, she welcomed the elite into her salon. In her parlor, she often read her fairy tales aloud, but her stories were unrecorded until 1690 when madame finally put pen to paper. Once published, her written style echoed her conversational grace. Her first novel, the successful Story of Hypolitus, Count of Douglas, contained within its pages, her first fairy tale, The Island of Happiness. One visitor to her salon in Paris’s rue Saint-Benoît declared: “I knew Madame d’Aulnoy very well. One never became bored in her company. Her lively and playful conversation went far beyond her book.”

Portrait of Louix XIV, the Sun King. Public domain.

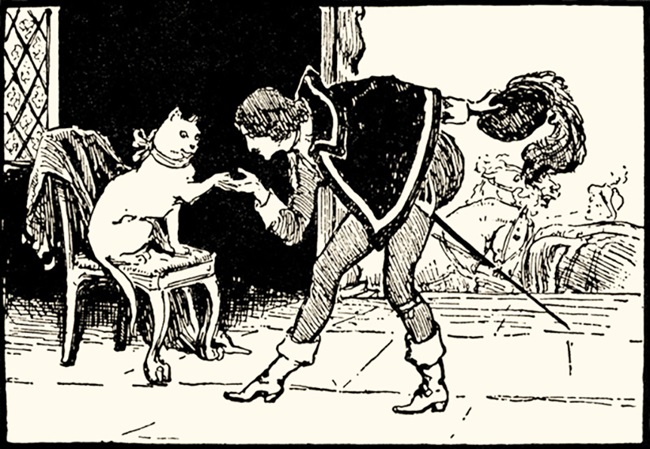

It wasn’t until 1697 that Madame d’Aulnoy’s nascent idea of fairy tales took off. The Contes des Fées (Tales of the Fairies) is her most famous work; the first set of 15 published in 1697, followed by another nine the following year. First written for adults, and perhaps because she was disillusioned with Louis XIV, these fables could be interpreted as a critique on his regime. As we learned above from young Marie-Catherine’s false accusation of treason, criticizing the king just wasn’t done if you wanted to keep your head. Her criticism was couched in fantasy; after all, who could get angry at a talking cat…

The White Cat was one of Madame d’Aulnoy’s most favored stories. Under the spell of a feline façade, a beautiful princess solves a prince’s quests set for him by the “king.” In The Bluebird, Prince Charming is transformed by his beloved’s ugly stepmother. As the beautiful bird perched on the heroine’s finger, she thought, “how strange it was that she was holding the greatest man in the world in the palm of her hand.” By the way, in Madame d’Aulnoy’s fairy land, kings are always handsome, no matter how inept they are!

The Contes des Fées (Tales of the Fairies) by Madame d’Aulnoy

D’Aulnoy often used the trope of turning characters into animals. Manners maketh the man, and gentlemanly conversation could win the womens’ hearts even if spoken from the mouths of men disfigured into donkeys, frogs, or serpents. Metamorphosis could be used to solve a problem and androgenous heroines abounded. Girls morphed into boys because the lot of a 17th-century woman was not an easy one. If puzzled kings fell in love with cross-dressing soldiers, so be it. In d’Aulnoy’s works the clever one is the young female protagonist who displays a woman’s view on fidelity, honor and love. D’Aulnoy’s tales place women in greater control of their destinies than they were granted in real life.

Illustration from the fairytale “L’Oiseau bleu”. Unknown artist. 19th century. Public domain.

Love and happiness were only realized after surmounting great obstacles. Suffering in d’Aulnoy’s stories could be overcome by supernatural means, magical objects, or powers. Fairies became godmothers casting protective spells. But woe betide those who inadequately compensated them, for fairy godmothers are quick to anger. There’s vengeance in these stories, a retribution perhaps for the romantic, youthful ideals that were snatched from her.

Madame d’Aulnoy’s tales were expanded into parlor games. It became customary at her salons for visitors to recite their own stories or to dress up as one of Madame D’Aulnoy’s characters. Her costumed guests were her own rebellious fairies. D’Aulnoy too was a rebel, tacitly criticizing what we now recognize as patriarchal values.

Illustration by John Gilbert of Madame d’Aulnoy’s “The Yellow Dwarf.” Public domain

There were always intrigues in the writer’s life and more heads rolled. Madame D’Aulnoy apparently assisted her friend Madame Angelique Tiquet in the attempted assassination of her abusive husband. Madame Tiquet was beheaded and her servant was hanged for wounding Councillor Tiquet. Madame d’Aulnoy avoided persecution despite her alleged involvement, but kept a low profile until her death six years later in 1705. She did not “live happily ever after.”

A depiction of Madame Tiquet at her execution clutching her crucifix. Line Engraving with etching by H.R. Cook after G. Cruikshank. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wikimedia commons

Madame d’Aulnoy was one of the most popular writers in her lifetime. In the late 18th century, her tales were adapted into a format more suitable for children. Read by young and old, her stories remained popular in Europe. Some were read aloud as far as French Canada and francophone regions of the southern United States. She had a huge effect on the stories of the Brothers Grimm.

Honoré de Balzac read Madame d’Aulnoy’s stories, as did Gustave Flaubert. Maurice Ravel set some of them to music for his Mother Goose Suite. The British dramatist James Planché adapted them for the London stage in a series of “fairy extravaganzas.” Alas, Madame’s status has since languished. Her influence on Western literature should not be forgotten.

Lead photo credit : Illustration of Madame d'Aulnoy's "White Cat" fairy tale by Jacomb Hood

More in Charles Perrault, Fairytales, Madame d'Aulnoy