Jean de Brunhoff and his Unforgettable Elephant – BABAR!

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

We love our Babar books! Photo: Bonjour Paris

“In the forest, a little elephant is born. His name is Babar.” It was a storybook childhood for the little elephant. On the savannah little Babar’s mother softly rocks him in a hammock with her gentle trunk. Other young pachyderms frolic in a waterhole. They picnic, play ball, and piggyback their monkey friends. This jungle paradise is torn asunder when – Bang! – an evil gun blast orphans Babar.

It was a storybook childhood for Laurent and Mathieu de Brunhoff too. In their privileged fairy tale, the happy sons of Jean de Brunhoff rode their bicycles, visited their tree house, and played hide & seek, romping like little suburban monkeys with their cousins at their grandparents’ estate. And then, in 1937 the dream was over. Their father, the French artist who brought to life one of the most enduring fictional characters of all time, was dead from tuberculosis.

Many junior protagonists found in children’s books are parentless and carry on regardless – Harry Potter, Oliver Twist, Anne of Green Gables to name but three. This literary trope forces the orphaned child to struggle against the unexpected in his or her own way. These kids are magnets for trouble but often a magical dose of luck sets them straight. These waifs and strays are free to run wild and live large and daring lives. Babar was no exception. Babar’s reaction to his mother’s death was to high-tail it to the city. Running on and on he miraculously arrives at a large town that is oh-so-very much like Paris, including a great bronze lion like the one who oversees the traffic at Place Denfert-Rochereau in the 14th arrondissement.

Babar soon learns to handle himself in all situations with help from a kindly old lady (and her purse) who teaches him to be two-footed and who instantly understands that he is longing for a good suit. And what a suit it is – in Babar Green – so iconic it should have its own paint chip. Inexplicably the marché has clothes in size ‘Elephant.’ The old lady becomes his best friend forever. She maintains Babar at her pied-à-terre like a kept man. There, he is a habitué of the good life and the fine food and lively conversation he enjoys softens the pain of his mother’s death.

Writer and illustrator Jean de Brunhoff. Public domain.

Jean de Brunhoff lived a good life too. Born in Paris on December 9, 1899, de Brunhoff was the fourth and last child of publisher Maurice de Brunhoff, and his wife Marguerite. The Place Denfert-Rochereau was the bustling Paris corner where Jean grew up. From № 4 he would overlook Bartholdi’s heroic lion every day. After graduating from the prestigious L’Ecole Alsacienne, de Brunhoff joined the French army at the end of the First World War, but luckily saw no action. Deciding to become a professional artist, Jean studied painting with Othon Friesz at the Académie de la Grand Chaumière in Montparnasse. He was attracted to the relaxed lines and open brushstrokes of Raoul Dufy and produced landscapes, portraits, and still lifes that are thought to foreshadow his Babar books. He couldn’t earn his living as a painter so he tried his hand as an illustrator, supported by an allowance from his parents and parents-in-law.

In 1924 de Brunhoff had married the elegant and serene Cécile Sabouraud, and the de Brunhoff sons, Laurent and Mathieu, followed in 1925 and 1926. A tall and attractive man, Jean’s personality revealed his handsomeness was more than skin deep. Jean was tactful, friendly and natural. He was especially attentive to his youngsters. At a very young age Laurent and Mathieu learned to ski in Vermala, staying in the French Swiss ski resort for several months every winter. The family split their time between their skiing holidays, their apartment in Neuilly, in Paris’ northwest, and Cécile de Brunhoff’s parents’ walled mansion near the Marne. Free from the worry of school schedules, the boys continued their education through correspondence lessons. It was a blissful time. The four enjoyed a comfortable life.

One summer’s evening back at the Villa Lermina, Grandpa’s house in the Paris suburb of Chessy – now encroached upon by Disneyland Paris, – Mathieu had a tummy ache. Mama Cécile nestled herself between her boys aged four and five and spontaneously created the story of an intrepid and well-mannered elephant in the hope of soothing her youngest son. The next day the boys excitedly repeated the story to their artistic father. Laurent de Brunhoff interviewed in 2014 for an article in National Geographic remembers, “the next day we ran to our father’s study, which was in the corner of the garden, to tell him about it. He was very amused and started to draw.”

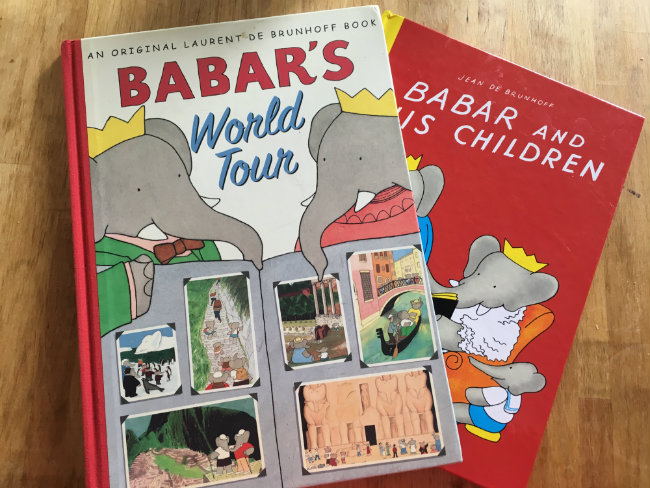

An excerpt from one of our favorites, “Babar and his Children” by Jean de Brunhoff. Photo: Bonjour Paris

Jean wrote down the story that Cécile had told their boys. According to Laurent de Brunhoff in Simon Worral’s National Geographic interview, that was how the story of Babar was born. “My mother called him Bébé elephant. It was my father who changed the name to Babar. But the first pages of the first book, with the elephant killed by a hunter and the escape to the city, was her story.” Jean embellished the story with illustrations and made the tale into a book, just a single copy, intended only for his sons. However, as his brother and brother-in-law worked together in the publishing business, it wasn’t long before they persuaded Jean to allow them to publish the story. Originally the title page of the Story of Babar was to have read “as told by Jean and Cécile de Brunhoff,” but unfortunately Cécile had her name removed because she thought her role in the book’s creation was a minor one.

Although Cécile de Brunhoff centered the resilient little Babar on the African savannah, she quickly introduced him to the pleasures of her familiar stomping grounds. The story was imbued with the charm of the de Brunhoff’s actual cosmopolitan existence. When Jean de Brunhoff elaborated on the first story and in the six subsequent volumes, he was able to capture the essence of the courtly behavior of their own lives. Babar and his kissing cousin/wife Celeste became king and queen of their realm. It was only natural to instil his heroes with gentle manners and kindness in conjunction with a worldly intelligence.

The upper-class world of the de Brunhoffs and the Sabourauds is revealed in morning suits, spats and spectacles and the bergères big enough for fat elephant bottoms. In the Paris-like city Babar enjoyed the minutiae of an urbane existence. He partakes of fine food, sleeps in a cozy bed, takes time for an extended exercise session, bathes in a claw foot tub, motors along the scenic Marne and holds forth at the Old Lady’s salon, describing life in the great forest. It shouldn’t be surprising that Jean de Brunhoff loved the words of Marcel Proust. Nevertheless, Babar’s elephantness isn’t forgotten. Even the smallest of children will see the irony in the world’s largest land mammal floating in a balloon, downhill skiing, and finding clothes in a department store that accommodates an XXXL.

The in-laws’ Editions le Jardin des Modes bought l’Histoire de Babar in 1931 the year after it was written. They reproduced the art and handwritten script exactly as they were in de Brunhoff’s large format notebook. At 10 ¾ x 14 ½ inches the book itself was elephantine. Its sheer size made it and all subsequent books memorable and unique objects.

The book was a success. After his first foray into publishing, Jean de Brunhoff would soon be recognized as the father of the modern picture book. Thousands of children and adults in France read along as Babar struggled and triumphed. Each year de Brunhoff wrote another volume about Babar. The books were soon translated and readers in North America and England began to follow the adventures of Babar and his family. Editions le Jardin des Modes was a subsidiary of Condé Nast and to that point had never published a book that wasn’t about fashion. The parent company was dubious about Babar but since he was an instant success and they published a second edition in 1935. The French publishing house Hachette later bought the rights to the Babar series and have been publishing Babars since the early 1950s. Today the book has been translated into at least 18 languages. But to Laurent and Mathieu, the exploits of Babar were their very own.

In 1936 de Brunhoff’s third son Thierry was born. Jean provided Babar and Celeste with three children too, the triplets Pom, Flora and Alexander. More and more Jean asked the older children for their suggestions for the books. On occasion the little boys supplied their own content. Zephir, the beloved monkey character was added at their behest. He asked for their advice on color choices and by the age of 10 Laurent regularly sketched his father’s elephants.

Like the tragic battles and deathly snakebites that occurred within the pages of Babar, tragedy struck the de Brunhoffs too. After seven blissful years crafting and perfecting Babar, Jean de Brunhoff was diagnosed with spinal tuberculosis in the spring of 1937. His case was deemed incurable and Laurent, Mathieu and Thierry remained in the Alps with their papa long after the back-to-school deadline was gone. Jean de Brunhoff died in October of 1937 and is buried at Père Lachaise. Their picture-perfect childhood was over.

Widowed at 33, Cécile was left to raise her three boys. Her father’s death followed just a year after Jean’s and the house at Chessy sold. Then came the War and the ensuing occupation of Paris. Sadly Jean was gone but it was not au revoir for Babar. When his publisher-uncle Michel de Brunhoff asked Laurent to assist with the coloring of Jean’s last two Babar stories, the teenager Laurent was happy to help. At 21, Laurent, then struggling as an abstract painter in Montparnasse, took up the pen in 1946. He had drawn the elephant for his own amusement when he was young – now it was his turn to recreate Babar in book form. Babar was once again King of the Elephants.

Laurent de Brunhoff’s stories led Babar farther afield – to distant planets, the underground world and America. In 2002 Babar demonstrated a series of asanas in Babar’s Yoga for Elephants. Laurent has created well over 30 Babar stories and now lives in Key West, Florida.

Now into his nineties Laurent has carried on the tradition of Babar for seven decades. His gentle mother Cécile died in 2003 just a few months shy of her 100th birthday. She never remarried. Perhaps she couldn’t forget.

There are understated traces of Babar remaining in Chessy, which speak calmly against the noise that is nearby Disneyland Paris. A statue of Babar’s wise and wrinkly mentor Cornelius is located at the elementary school named for him. Opened in 1994 by Laurent and Mathieu de Brunhoff, it also contains a room named after Babar’s queen Celeste. The Group Scolaire Cornelius is just steps away from the Chessy manor now known as Villa Muscadelle at 83 rue Charles de Gaulle.

The art of Babar: The work of Jean and Laurent de Brunhoff by Nicholas Fox Weber. New York: Harry Abrams, 1989.

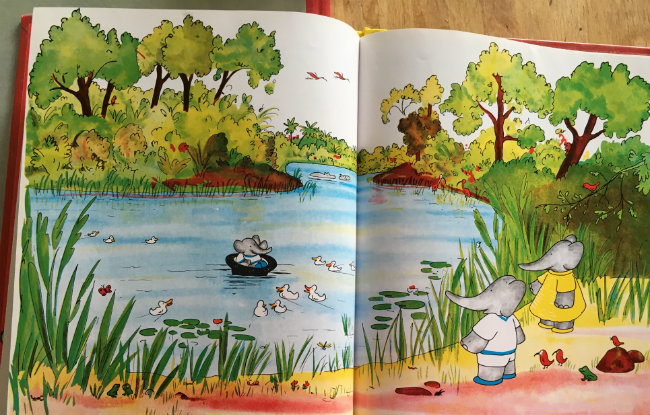

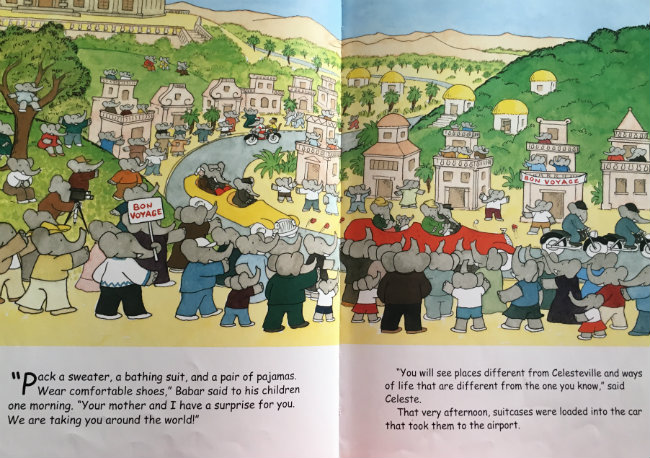

An excerpt from Babar’s World Tour by Laurent de Brunhoff. Photo: Bonjour Paris

Lead photo credit : We love our Babar books! Photo: Bonjour Paris

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY