Infinite Jest: The Brilliant Satire of Parisian Cartoonist, JJ Grandville

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

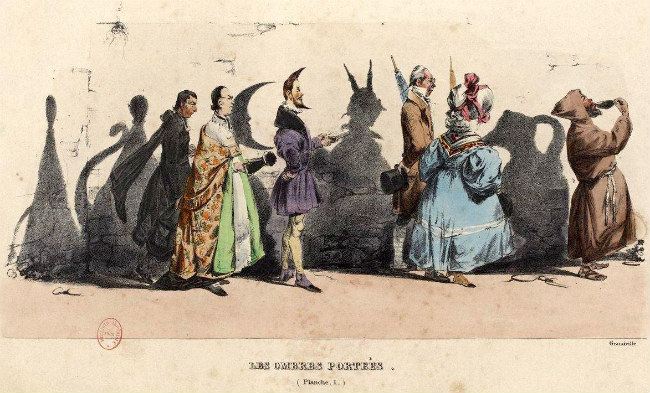

Illustration de Grandville dans le journal La Caricature du 18 novembre 1830 / Public Domain

No one is certain who invented the caricature. Some art historians think it might have been Leonardo da Vinci, whose studies of grotesque heads led his devotees to the realization that contorted aspects of physiognomy could serve a satirical purpose more directly than pure representation. And no one epitomized that representational style more than the great Parisian cartoonist, Jean Ignace Isidore Gerard, known as J.J. Grandville.

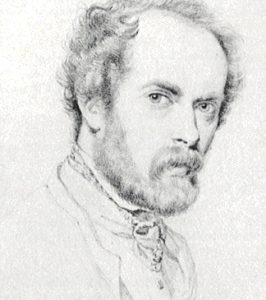

Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard Self Portrait / Public Domain

J.J. Grandville was born in 1803 in Nancy, France, to a theatrical and artistic family, (the name “Grandville” was his grandparents’ professional stage name). He was an illustrator and lithographer known for his poetically unrestrained, imaginative drawings and his sardonic caricatures created during the 19th century reign of King Louis-Philippe. Grandville received his first instruction in drawing from his father, a painter of miniatures. He displayed an early talent for rendering images showing the features of his subjects in an exaggerated way, precisely the definition of “caricature”.

After attending school, Grandville began designing costumes for a comic opera theater troupe, and at the age of 21 he moved to Paris. Concurrently, as his skills matured, lithography came into widespread use for producing salable prints. Lithography is a method of printing from a flat surface, such as a smooth stone or a metal plate which has been prepared so that the ink will only adhere to the design that will be printed. Lithography suited Grandville’s sensibilities. He developed an extraordinary style that employed precise lines and cross hatching comedically depicting a fantastical combination of humans with animal characteristics in the clothing and settings of the time.

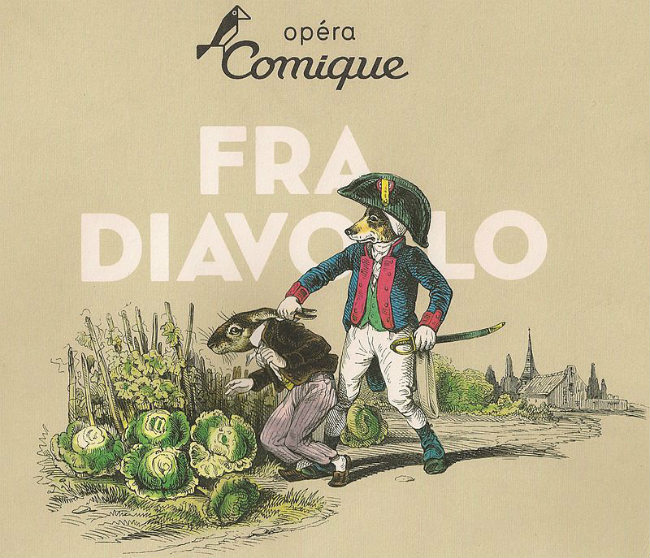

Lithography by Grandville, 19. Jh / Public Domain

The public was keen for depictions of contemporary events and personalities offered by Grandville’s caricatures which satirized bourgeois Parisians. His drawings were wildly popular and in 1826 he published 12 lithographs entitled Les Tribulations De La Petite Propriété (Tribulations of Small Property), followed in 1827 by 12 lithographs entitled Les Plaisirs de Tout Âge, (The Pleasures of All Ages). In 1827 he published La Sibylle des Salons, (The Sibyl Lounges ), a collection of 53 lithographs, an illustrated deck of Tarot cards, and the parlor game, Old Maid.

Lithographie “Ah! J ‘t’y prends mon lapin… à manger les choux du voisin…” – Les Métamorphoses du jour (1828–29) de Grandville / Public Domain

Le Metamorphoses du Jour, (Metamorphosis of the Day), published in 1828, established his fame. The volume, originally published as a folio of hand-colored lithographs, contains a series of 70 scenes in which individuals with the bodies of men and faces of animals are made to play a human comedy. These drawings are remarkable. Owners of the works would share them with friends, passing them around as a form of entertainment at gatherings. These first editions of the folio are almost impossible to find and have been subjects of forgery.

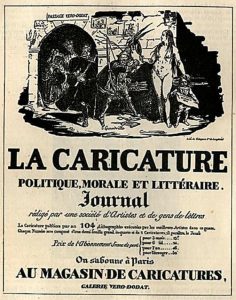

Advertisement for La Caricature, Politique, Morale et Littéraire Journal, Illustration by J.J. Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard) Lithograph and Letterpress, 1830 / Public Domain

In 1830, Grandville created the masthead for the first issue of La Caricature, an illustrated weekly newspaper founded by Charles Philipon, and went on to produce 120 caricatures for the publication covering events and ideas related to the “…moral, religious, literary and stage”. Another notable artist featured in the publication was Grandville’s contemporary, Honoré Daumier, a printmaker, caricaturist, painter, and sculptor. Concurrently, in 1830 Louis-Philippe ascended to the throne as King of France, and for the next five years Grandville published cartoons critical of the King as a betrayer of liberal ideals. However, by 1835, Louis Philippe turned his back on his initial promises to support a free press. The caricatures making fun of the hypocrisy and corruption of the government were too provocative to ignore. There were many battles and occasional arrests over the cartoons. Eventually, the government shut down La Caricature. The ensuing censorship pushed Grandville to do more book illustrations. I have read that this was a relief to Grandville who did not relish the continual conflict.

Grandville subsequently turned his focus and energy towards creating illustrations for popular books, including editions of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and Miguel Cervantes’ Don Quixote. In 1844, his illustrations for Le Diable à Paris, (The Devil in Paris), were used by the social critic Walter Benjamin for his study of Paris as an urban organism. Perhaps his most original contribution to the illustrated book form was Un Autre Monde, (Another World), which approaches the realms of pure surrealism. Leading members of the Surrealist movement such as André Breton and Georges Bataille recognised in Grandville a significant inspiration for their movement.

Title page from “Fleurs Animées” by the french artist Grandville (1803-1847) / Public Domain

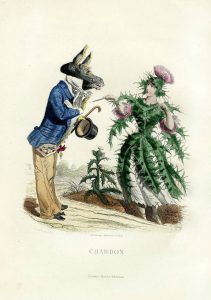

Tragedy cast deep shadows on the last 10 years of Grandville’s life and he suffered unbelievable losses. He married Marguerite-Henriette Fischer in 1833. Their first son, Ferdinand, died at age four. Their second son, Henry, choked to death on an piece of bread at age three. This was witnessed by both parents. Henriette died as a result of peritonitis following the birth of their third son George in 1842. Grandville then married Catherine Marceline Lhuillier in 1843 and she had his fourth son, Armand. The third son George, by his first wife, Marguerite-Henriette, died at age four in 1847. This was a mortal blow to him. He was described as going insane in the end, and died three days later on March 17, 1847. He was just 44 years old. His last work, Les Fleurs Animées, was published posthumously. This book is considered to be one of his most supreme achievements.

Illustration “Chardon” (thistle) from “Fleurs Animées” by the french artist Grandville (1803-1847) / Public Domain

After his death, Alexandre Dumas, the celebrated author of The Three Musketeers, and friend of Grandville, described celebrities of the day coming to Grandville’s art studio. They sat for caricatures and conversations in his garret atelier among drawings on all surfaces mingling with the eclectic collection of objects and creatures that inspired him. He said, “…Grandville had a delicate and sarcastic smile, eyes that sparkled with intelligence, a satirical mouth, short figure, large heart and a delightful tincture of melancholy perceptible everywhere.

Grandville’s extraordinary skill, sharp analysis of character, marvelous ingenuity and humor which was tempered and refined by a sober thoughtfulness, was a rare combination in any artist. He is buried in the Cimetière Nord of Saint-Mandé just outside Paris.

Lead photo credit : Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard Self Portrait / Public Domain

More in Art, caricatures, cartoons, comedy, comic art, Franch artists, French Art, French cartoons, French humour, Grandville