Did You Know Alexandre Dumas Wrote a 1,150-Page Cookbook?

Alexandre Dumas in 1855. Public Domain

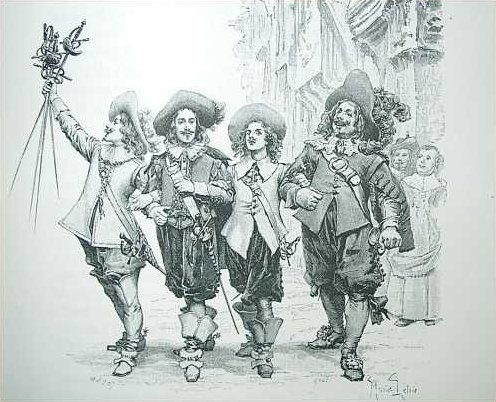

In 2002, for the bicentennial of Alexandre Dumas’ birth, then French President Jacques Chirac arranged a ceremony honoring the renowned author by reinterring his coffin at the Panthéon in Paris. Four Republican guards dressed as the 4 Musketeers conveyed Dumas’ casket through the streets of Paris to the famous mausoleum, where his remains were laid to rest alongside those of Victor Hugo and Émile Zola. Dumas, who wrote in an amazing variety of genres (plays, essays, short stories, histories, historical novels, romances, crime stories and travel books), and published over one hundred thousand pages in his lifetime, also wrote a cookbook: the 1,150 page, Le Grand Dictionaire de Cuisine. He was not only a prolific writer, but a consummate gourmet cook and bon vivant.

Alexandre Dumas was born Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie in 1802 in Villars-Cotterêts, Picardy, France, to Marie-Louise Labouret and General Thomas-Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie. Dumas’ nom de plume derives from his grandmother on his father’s side, Marie-Cosette Dumas, a Haitian slave, and his grandfather, the Marquis Alexandre– Antoine Davy de La Pailleterie.

Alexandre Dumas in his library, by Maurice Leloir. Public Domain.

Dumas’ father, Thomas-Alexandre, rose to the distinguished rank of general at the young age of 31 under Napoléon Bonaparte’s command, but died a few years later when Dumas was still a child. His mother, Marie-Louise, struggled to make ends meet and provide an education for her son using the few resources she had. The precocious Dumas’ young appetite lusted for literature and he read everything he could find, while his mother’s stories about his father’s bravery during Bonaparte’s campaigns fueled his imagination. And, although poor, his paternal grandfather’s aristocratic lineage and his father’s illustrious reputation eventually helped him secure a place in school, and then, in 1822, at the age of 20, a position at the Palais Royal in Paris in the office of the Duc d’Orléans. In his spare time, while working for the Duc, Dumas used his accumulated knowledge to begin writing plays for the theatre. His first plays, written in a Romantic style similar to his contemporary (and later rival) Victor Hugo, were so popular that he made enough money to quit his job and write full-time.

A Maurice Leloir illustration in the Appleton edition of The Three Musketeers. Public Domain

In 1830, Charles X was overthrown and the Duc d’Orléans became the ruler of France as King Louis-Philippe. The new monarch greatly improved the general economy of his country, thus increasing Dumas’ revenues, enabling him to afford to serialize his plays. Subsequently, he founded a writing studio with a willing cadre of assistants and collaborating writers. By 1850 Dumas had written The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, among many others. His novels were so popular they were first translated into English, and then a hundred languages, and were eventually transformed into over 200 films. During this period he earned large sums of money, more than enough for him to spend on sumptuous living: grand love affairs (even though married he had over 40 mistresses), beautiful houses, rich foods and expensive wines. A man of tremendous energy and enormous self-esteem, he was described as a giant, both in mind and body. Dumas boasted, “If I were locked in a room with five women, pens, paper, and a play to be written, by the end of an hour I would have finished the five acts and had the five women.”

The idea of writing a cookbook had been in Dumas’ mind for years. He would begin it, he said, “…when I caught the first glimpse of death on the horizon”, and in 1869 he retreated to Normandy with his cook. Six months later, his Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine was finished. Of his book he said, “It will be read by wordily people and used by professionals. In cookery as in writing, all things are possible.” True to his vision, Dumas succumbed to a stroke in December 1870.

Dumas’s epicurean tour of the alphabet, from absinthe to zest, is a treasure chest of hundreds of recipes, and reminiscences, and, though written without measurements, it is a master storyteller’s collection of consummate prose, worthy of being read as literature, just as M.F.K Fisher’s An Alphabet for Gourmets (1949) was first enjoyed almost a hundred years later. Le Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine was published posthumously in 1873 and remained in print in its original form until the 1950s. In 1882 Le Petit Dictionnaire de Cuisine was published consisting of just Dumas’ recipes. In 2005, Alexandre Dumas’ Dictionary of Cuisine was edited, abridged and translated into English by Louis Colman.

Alexandre Dumas’ Dictionary of Cuisine

Le Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine is truly a monumental work. Not only amazing for its collection of old world recipes, stories and historical facts, it creates a cumulatively unique portrait of the man himself. Dumas avowed he would not eat pâté de foie gras because the ducks and geese “…are submitted to unheard of tortures worse than those suffered under the early Christians.” And his description of the perfect number of dinner guests within the parentheses of ancient history still holds true today: “…Varro, the learned librarian, tells us that the number of guests at a Roman dinner was ordinarily three or nine — as many as the Graces, no more than the Muses. Among the Greeks, there were sometimes seven diners, in honor of Pallas. The sterile number seven was consecrated to the goddess of wisdom, as a symbol of her virginity. But the Greeks especially liked the number six, because it is round. Plato favored the number 28, in honor of Phoebe, who runs her course in 28 days. The Emperor Verus wanted 12 guests at his table in honor of Jupiter, which takes 12 years to revolve around the sun. Augustus, under whose reign women began to take their place in Roman society, habitually had 12 men and 12 women, in honor of the 12 gods and goddesses. In France, any number except 13 is good.”

The château de Monte-Cristo, Alexandre Dumas’ home in Yvelines outside Paris. Photo: Moonik/Wikipedia

For Dumas a perfect dinner is also “a major daily activity which can be accomplished in worthy fashion only by intelligent people. It is not enough to eat. To dine, there must be diversified conversation which should sparkle with rubies of wine between courses, be deliciously suave with the sweetness of dessert and acquire true profundity by the time coffee is served.”

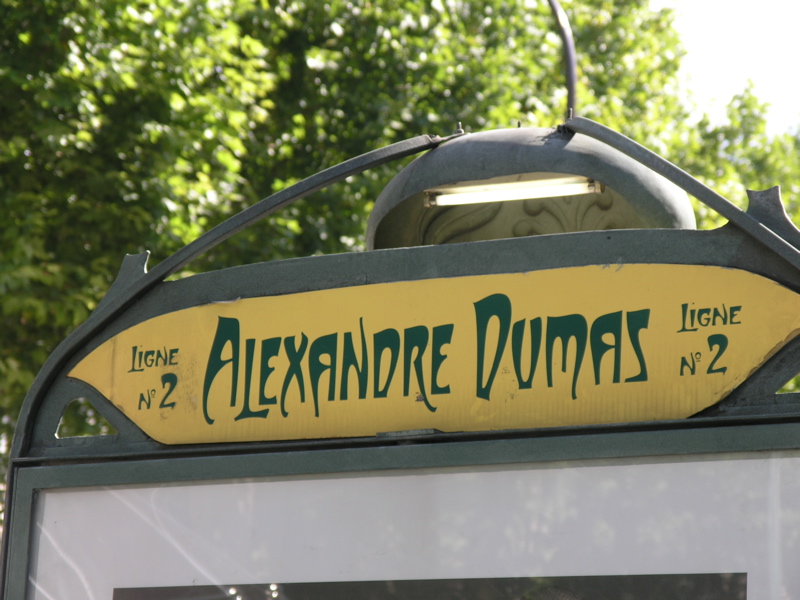

In 1970, the Paris Metro Line 2, on the border of the 11th and 20th arrondissements, was renamed after him, and a bust was mounted in medallion style on the side of the building on the corner of Boulevard Alexandre Dumas and Boulevard Voltaire. Dumas’ country home in Port-Marly, Yvelines, France, outside Paris, named after one of his most popular novels, Le Château de Monte Cristo, has been a museum since 1994. The estate has two chateaux and gardens which were built in 1846 by the architect Hippolyte Durand. The smaller of the two chateaux was built as a writing studio, which Dumas named the Château d’If after the setting of The Count of Monte Cristo, a small fortress island in the Bay of Marseille.

Entrance of the Alexandre Dumas metro station in Paris. Photo: sirkarm/ Flickr

Photo credit: Entrance of the Alexandre Dumas metro station by sirkarm/ Flickr

Lead photo credit : Alexandre Dumas' Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine

More in Alexandre Dumas, French authors, French cookbooks

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY