Commissioner Zamaron: The Artists’ Police Friend with Benefits

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Modigliani often flew into rages. He drank too much. He smoked hashish. When the artist was entrusted to buy cocaine for his friends he came back sniffing yet empty-handed. When he palled around with the drunken and damaged painter Maurice Utrillo, their antics would often result in them ending up in the local police station in the rue Delambre. Commissioner Léon Zamaron would be called in. For a pittance, Zamaron would buy paintings off this couple of drunkards. In exchange, the Commissioner released the painters after their night of drinking ended peaceably at the station.

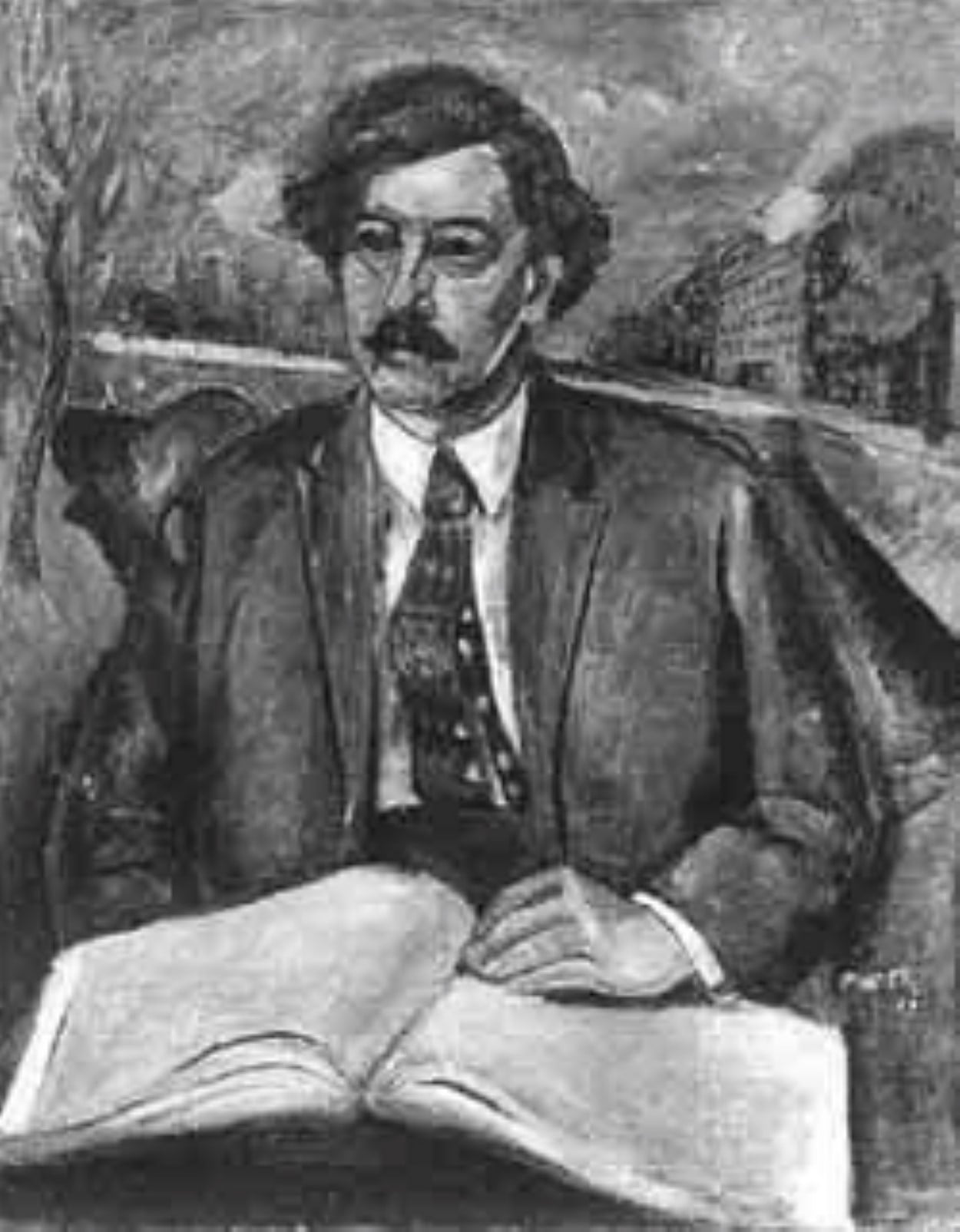

Léon Zamaron by Marek Szwarc.

Guided by his generosity and his love of painting and painters, Zamaron became the patron and protector of a number of artists in distress — artists whose works are now known worldwide. Zamaron’s art collection constituted one of the most important collections of modern art — but little is known of him.

Henry K Epstein, Nature morte aux fleurs. Public domain

At the Paris Prefecture of Police, Léon Zamaron was the official in charge of all foreigners and became a friend in need to the city’s artists. When the First World War ended there were many hangers-on — refugees in the name of art reluctant to return to their home countries. They wanted to experience what the cutting edge, yet cut-rate city of Paris offered. Paris was swept up by the Roaring Twenties, but the neighborhood most caught up in the effervescent spirit of the time was Montparnasse. Artists and writers of this time frequented the bars and cafés around the crossroads of the Boulevard Montparnasse and the rue Vavin: Le Dome, Le Select, La Rotonde, La Coupole. Léon Zamaron witnessed the creativity of this group.

Mme Zamaron by Suzanne Valadon. At the MoMa. (c) 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York – ADAGP, Paris Mme Zamaron

Whenever a painter ran into trouble Zamaron came to the rescue, helping to solve their administrative issues and get their papers in order, or salve their misdemeanors. When not on duty he would often show up at the Le Dome or La Rotonde spending a long night sitting at the artists’ tables and perhaps running interference against Eugène Descaves, another Parisian policeman who was a less tactful collector of art.

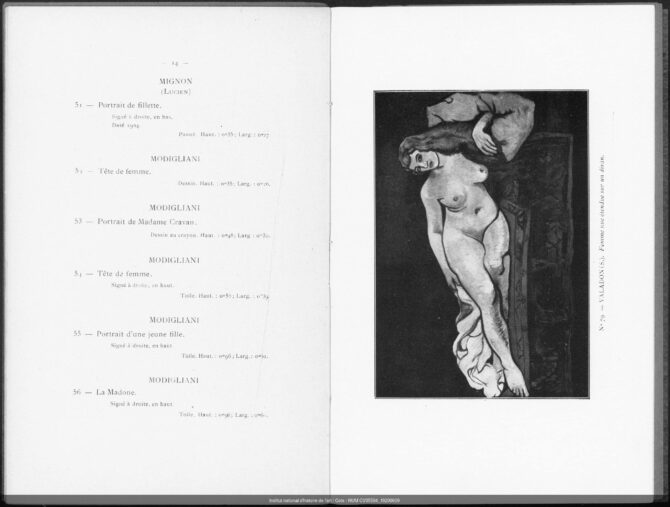

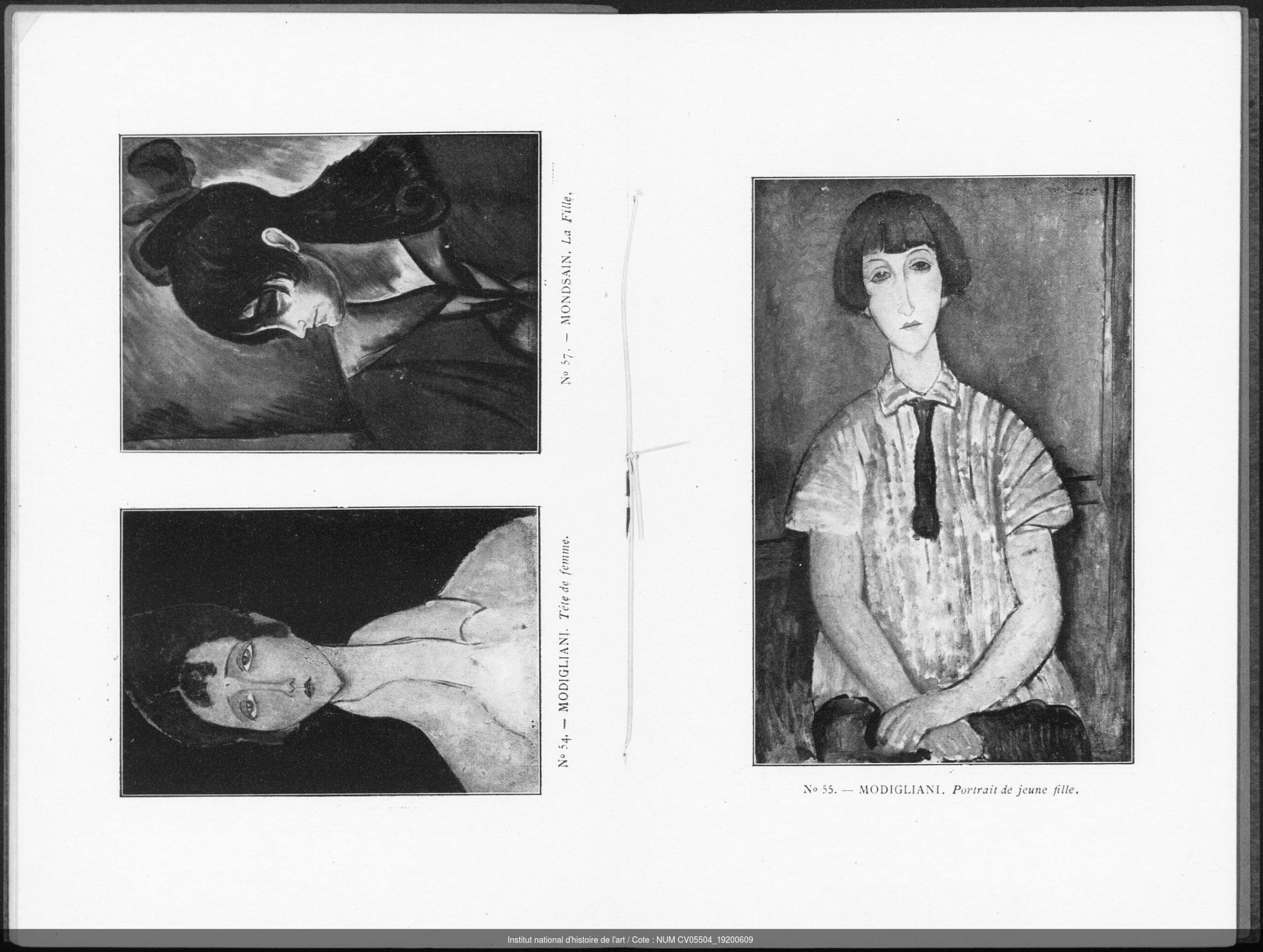

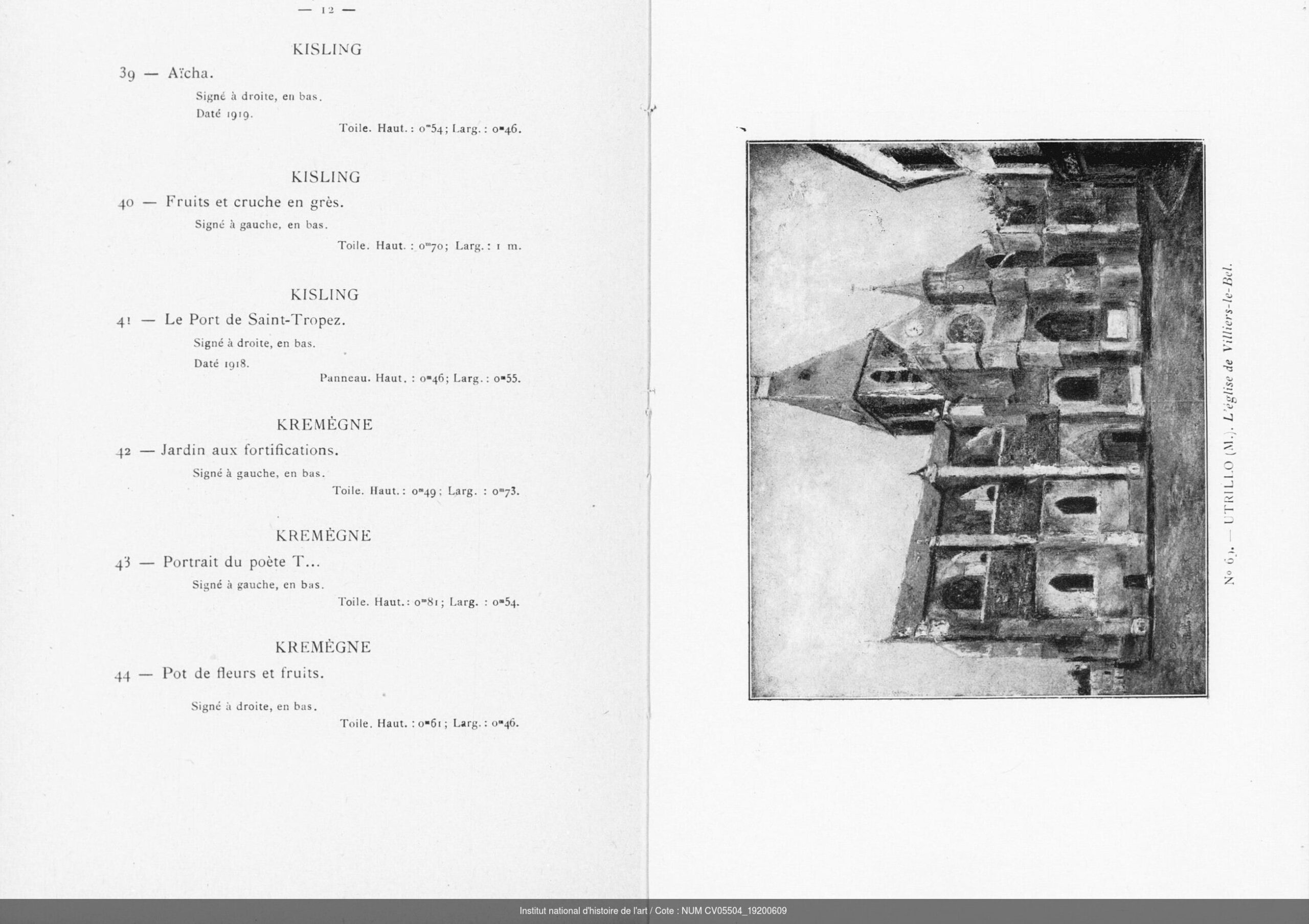

Part of Zamaron’s 1920 Auction Catalogue. (c) Digital Collections of the INHA Library/ The Institute National d’histoire de l’art.

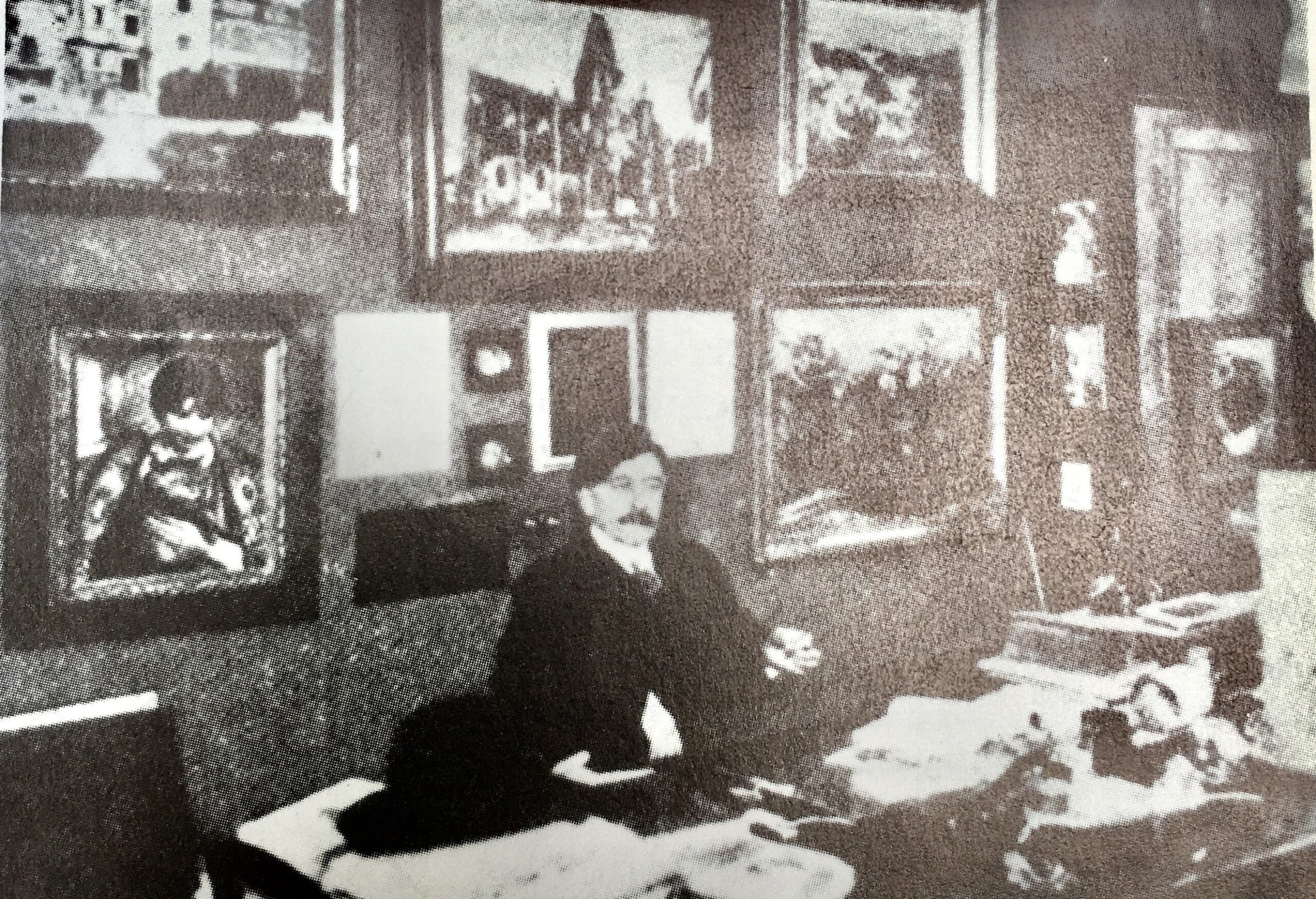

Zamaron was a Police Commissioner from 1906-1932. His office walls at the Prefecture de Police were a testament to the artists’ gratitude. Nicknamed the Zamaron Museum, his office was absolutely covered by the works of Modigliani, Soutine, Chagall, Foujita, Valadon, her always debauched son Utrillo, Valadon’s paramour Andre Utter, and Maurice de Vlaminck. Zamaron was the first owner of Modigliani’s Portrait Woman in a White Coat.

Zamaron (C) “Kiki’s Paris” by Billy Kluver.

The collection could have been interpreted as a wall-full of bribes, but not all artists ran afoul of the law. Zamaron was simply the first point of contact for the foreign artists in Paris which resulted in him being one of their very first investors.

Although coyly hiding behind a level of anonymity, 85 lots of the collection of modern paintings belonging to ‘M. Léon Z’ went on sale Wednesday, June 9, 1920 at the famed auction house, the Hôtel Drouot. The contents of the catalogue revealed who the owner was. The huge assortment of modern paintings, watercolors and drawings were by now-famous names such as André Derain, Kees Van-Dongen, Raoul Dufy, Marie Laurencin, Amedeo. Modigliani, and Suzanne Valadon and her circle. With the proceeds of this sale Zamaron would go on to sponsor other artists; for example he entered into a contract with the Polish ex-pat Maurice Mendjizky. Zamaron bought 50 percent of his work for the next four years. As a result Mendjizky was constantly in demand to exhibit his work.

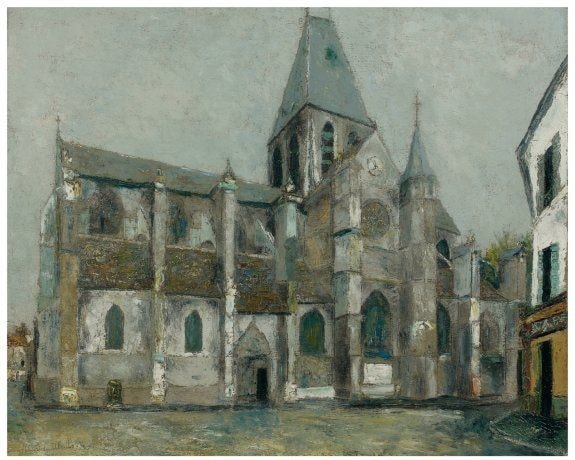

Maurice Utrillo, EGLISE DE VILLIERS-LE-BEL (VAL D’OISE), once seen on Zamaron’s wall

He was also the patron of artists whose names are lesser known to our 21st-century ears, such as Michael Kikoine, the Russian Marvena — lover of Diego Rivera, and Moise Kisling. Henri Epstein was the most gifted in Zamaron’s eyes, but Henri Epstein’s legacy was largely lost when he tragically met his end in the gas chambers of World War II. Zamaron’s choices influenced future collectors of Epstein’s work.

Part of Zamaron’s auction catalogue. (C) Digital Collections of the INHA Library/ The Institute National d’histoire de l’art.

Another police commissioner was Zamaron’s rival when it came to art collecting. Eugène Descaves was a source of trouble for the artists haunting the Vavin corner. Descaves would offer his services in exchange for a painting. Or sometimes he would buy a canvas putting down the first deposit and asking the painter to collect the remaining sum at the Prefecture. The artists were hard-pressed to darken the door of the police station to ask Descaves for the balance. Moise Kisling once punched a policeman in the face. Panicked, he called for Eugène Descaves who fined him two paintings.

Zamaron book cover

Descaves was only interested in buying work at the lowest possible price. He paid Maurice Utrillo 200 francs for enough of his quaint scenes to fill a Paris taxicab. Descaves was the first to sell parts of his collection to the Hôtel Drouot in 1919. He collected the same works as his colleague Zamaron, but notable additions were works by the poster artists Chéret and Steinlen, and paintings by Signac, Matisse and Picasso. Descaves had smoothed the way for Picasso’s marriage to the Russian Olga Khokhlova. The behavior of both men would probably not be tolerated today due to conflict of interest.

Léon Zamaron’s collection of modern art eventually topped more than 800 examples — all of which he lost at the gaming-table. When Zamaron died, the canny art collector left no fortune. He had been pursued by bad luck. His wife went mad, his mistress died of cancer, and his son died. He turned to gambling and his passion for cards ruined him and he had to sell his paintings one by one to pay his debts.

Lead photo credit : Police Commissioner Zamaron (C) Digital Collections of the INHA Library/ The Institute National d’histoire de l’art.

More in Art, artists, exhibition, gallery, painters, painting

REPLY