Basilica of Saint-Denis and the Medieval Miracle, Insights into the Cathedral Builders

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Lately I’ve been re-reading The Cathedral Builders, written by Jean Gimpel, a man of diverse interests born in Paris in 1918. During World War II he was involved in a Resistance group blowing up factories in and around Paris – preventing their takeover by the invading Nazis. Jean survived a concentration camp, but his father René, the eminent Parisian art dealer, did not. After the War, Jean set up a laboratory for the scientific study of the Old Masters. The Cathedral Builders, published 35 years ago, is a definitive study, dispensing with myth and magic and all the more commanding for that.

The facts contained in his first three sentences always astonish me: “In three centuries – from 1050 to 1350 – several million tons of stone were quarried in France for the building of 80 cathedrals, 500 large churches and some tens of thousands of parish churches. More stone was excavated in France during those three centuries than at any time in Ancient Egypt, although the volume of the Great Pyramid alone is 2,500,000 cubic meters. The foundations of the cathedrals are laid as deep as 10 meters, the average depth of a Paris Metro station, and in some cases there is as much stone below ground as above.” The statistics are eye-watering!

There is a wealth of documentation about the builders of these vast cathedrals yet historical truth was, and is, shrouded in legends of guilds, of secrets, of volunteer labor, and builder monks. The unraveling of legend had to wait centuries until the writing of three major works in our own time gave us truths more remarkable than any fiction: Les Chantiers des Cathédrales by Pierre du Colombier; Gold was the Mortar by H. Kraus, an American living in Paris, and Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, the review published in London by the Masonic Lodge of the Free Masons.

The term Free Mason owes a pedestrian beginning from “freestone mason.” To distinguish between those who worked with hard stone, hard hewers, quarrying the blocks, and those who worked or carved the chalky stone used for more delicate work such as sculpture, came “freestone‟ masons – the latter stone being “free‟ or portable. Freestone masons were distinguished from rough masons and gradually the portmanteau “freemason‟ was born. The medieval un maître maçon de franche peer became a master mason of freestone.

Viollet-le-Duc’s project to reconstruct the façade of the Basilica of Saint-Denis. Public domain.

We are indebted to Abbot Suger, Regent of France, for the influential rise of these great cathedrals, stone poems. As a young man he became an Oblate of the Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Denis and was eventually given it, with the title Abbot. It was Dagobert, the Merovingian king of the Franks in the seventh century, who re-founded the church as an Abbey of Saint Denis and Benedictine monastery. Suger was of humble origin and never concealed the fact. At eleven we are surprised to learn he attended the local school, perhaps his precocious intelligence gained him a place, it being Benedictine, an Order which has always championed educating those who showed a desire for it. Here Suger made friends with the future King of France. Young Suger held one burning ambition – he wanted to rebuild Saint-Denis, the Royal Abbey where the Kings and Queens of France were buried. And so, in time, he did.

It was a rocky road, we might smile and say “rough-hewn.” Suger rose in power and esteem and ran into Bernard of Clairvaux whose claims to wealth did not include gold altar pieces or soaring naves but to the glory gained by leading Crusades. However, each man had the wisdom to acknowledge their differences – the King himself being their common denominator. Suger seemed to attract the beautiful – halted in a work by lack of jewels he counted it a “droll but remarkable miracle‟ when monks from Citaeux and Fontevrault offered to sell him an abundance of precious stones: amethysts, sapphires, rubies, emeralds and topazes– alms given them by Comte Thibaud. Suger made exquisite use of them and, although we have lost most, a few examples remain in the Louvre museum.

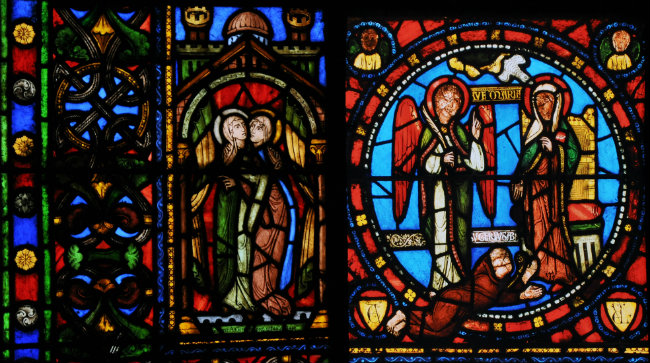

In the eleventh century, stonecutters and sculptors began to attract the interest of Christendom and monumental sculpture developed rapidly. From the twelfth century it became a major means of expression. Stained glass became important at the expense of frescoes, which declined as window areas increased and wall surfaces diminished. By becoming a sculptor, the stonemason graduated to the intellectual world of theologians, he learned from them, having the wonderful opportunity of accessing precious manuscripts for his depictions of the Holy: Christ, the Virgin, saints. His intellectual horizon broadened, he learned to look, to observe, to think.

Suger’s dream was dawning. And dawn happens in the East. Muslim scholars held a magnificent synthesis of scientific knowledge from India and from the great minds of classical antiquity – Euclid, Aristotle, Plato, Ptolemy. Al-Khawarizmi’s work on algebra dazzled European scholars, Al-Zarqali’s trigonometry proved the importance of sines and tangents, all of which influenced cathedral building. “In this way”, wrote Villard de Honnecourt, “the central point of a circle drawn with a compass can be found … thus the thickness of a column, only part of which is visible, can be calculated…”

Muslims, Christians and Jews were taught through the universities of Arabic Spain during those enlightened years, especially under Alfonso the Wise in the eleventh century. We cannot underestimate the remarkable contribution of Arabic culture to Europeans. Light had dawned and Suger’s dream for the Abbey of Saint-Denis was born.

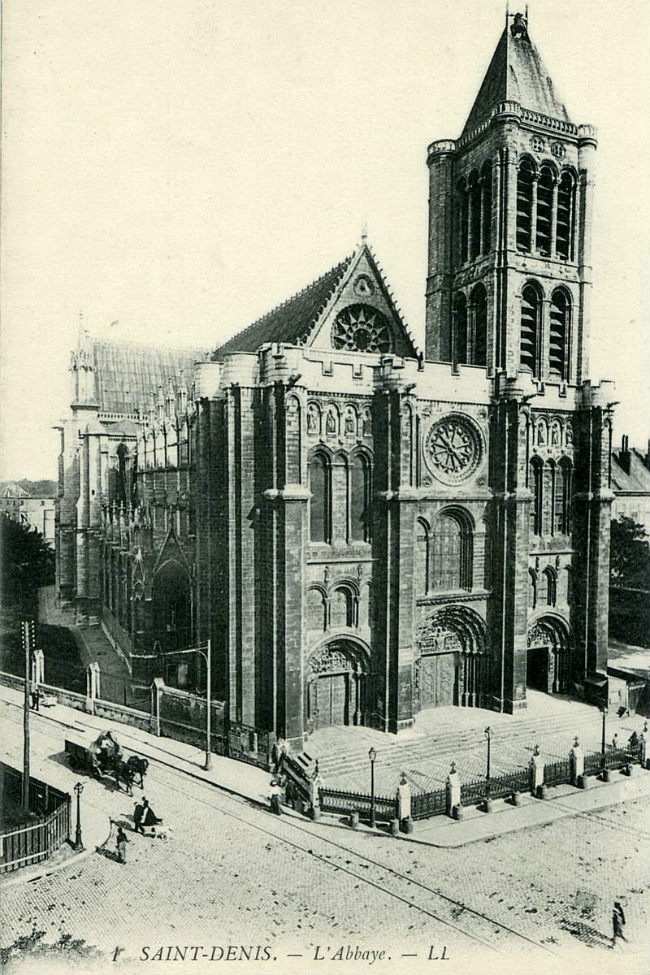

A postcard of the Basilica of Saint-Denis from the beginning of the 20th century. Public domain.

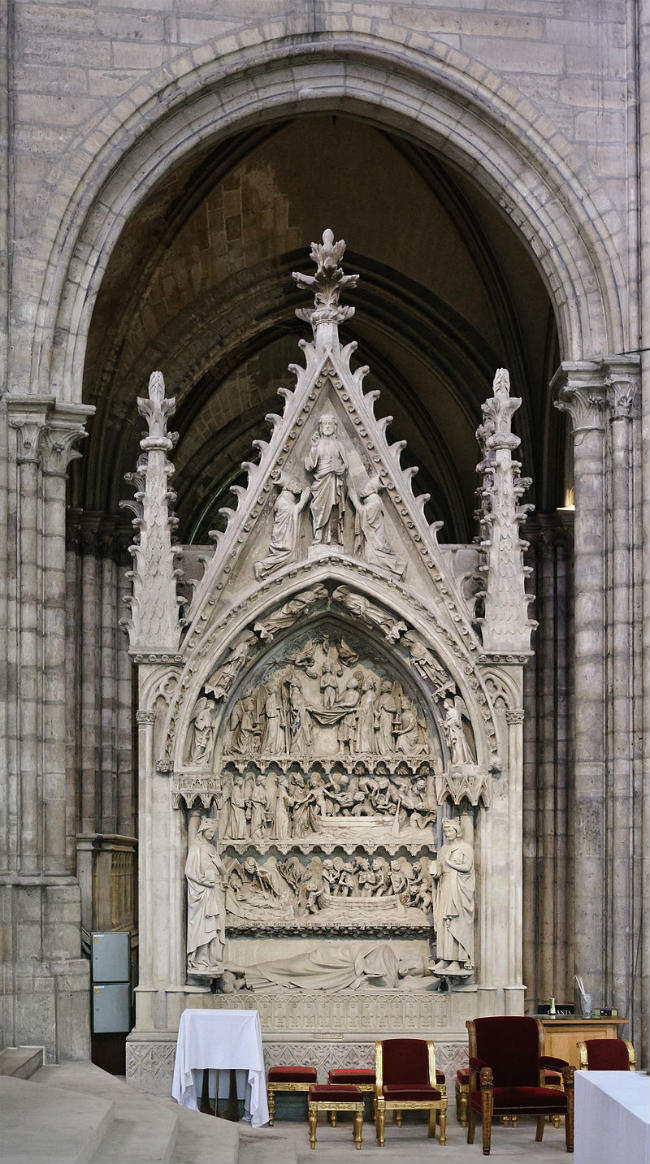

Suger’s fascination with light was more than aesthetic. He was a follower of PseudoDionysius the Areopagite, the 6th century mystic who equated the slightest reflection or glint as the Divine Light. Walls were turned to skeletons of stone, holding fenestration of jewel-like colors, drawing in light; flying buttresses supported his heroic folly – and it worked! He conceived radiating chapels, fan vaulted ceilings, and soaring naves. Sculptors, embroiderers, jewelers, enamelers, glass makers and carpenters created a world almost without boundaries in their efforts to create heaven on earth. The Basilica of Saint-Denis was an architectural landmark in its transition from Romanesque to Opus Francigenum. It was the prototype introduced to England, the Low Countries, Germany, Spain, northern Italy and Sicily. It became known later as Gothic.

Today we are inclined to the belief that the building of a Gothic cathedral would be impossible; that its flowering was some kind of alchemy – in a way it was, but the tragedy of its demise and our loss was more prosaic: the outbreak of the Hundred Years War in 1337. Five generations lost. The economy collapsed. The population decimated by famine, war and plague. In a climate of war, sculpture was a luxury none could afford. Cathedral sites closed and all the different masons were pressed into service, building fortified castles and keeps. The grandchildren of the men who built Saint-Denis, Chartres, Mont-Saint-Michel, and Notre-Dame de Paris were barely recognizable in the unfortunate generations of workmen obliged to spend their lives carving cannon balls. When their own grandsons began to carve again in the middle of the fifteenth century, the world had moved on and the older knowledge had been lost forever.

Tragedy came again with the French Revolution and the Abbey was completely demolished in 1792; only the church was left standing. Restored in the mid nineteenth century by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who restored the Cathedral of Notre Dame, the north tower was struck by lightning. We are fortunate enough to have a single lithographic plate of the apse and northern façade – but it is enough for us to imagine the wonder that was the Abbey of Saint-Denis.

The first monumental masterpiece of Gothic art, the Royal Basilica of Saint-Denis also houses the tombs of French royalty and ancient funerary sculptures (Dagobert, Pépin le Bref, François I, Catherine de Médicis, etc). For additional information, visit https://uk.tourisme93.com/basilica/, and for practical information, https://uk.tourisme93.com/basilica/practical-information.html

1 rue de la Légion d’Honneur, 93200 Saint-Denis. Metro: Basilique de Saint-Denis (line 13). Full price ticket is 9 euros. Website: www.saint-denis-basilique.fr/en

Purchase The Cathedral Builders on Amazon below:

Lead photo credit : Viollet-le-Duc's project to reconstruct the façade of the Basilica of Saint-Denis. Public domain.

REPLY