Aristocratic Acrobatics: Ernest Molier’s Amateur Circus

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The cult of the circus permeated Parisian society at the end of the 19th century when there were over 20 venues to delight in the circus arts: the Cirque d’Hiver, the Cirque Fernando and Hippodrome, by example. The circus was never considered high art but appealed equally to the laundry maid and the landed gentry and began to acquire a level of social acceptability among artistic and literary communities. The ever-so gossipy Edmond de Goncourt wrote a novel expounding on the noble qualities of the life of a circus performer in his Les Frères Zemganno for whom he consulted with the top artists of the circus world.

The social elite of the Belle Époque wanted in on the act. In 1880 a private, yet amateur, circus belonging to Ernest Molier gave them the chance. Cirque Molier was essentially an amusement by and for high society. Molier created a makeshift circus at his home in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, just steps from the Bois de Boulogne. His roster consisted of the Parisian elite who were proficient in riding, fencing, and gymnastics. Count This and Baron That from the best Parisian circles tried their hand and assumed a radical new identity in the process, if only for one day.

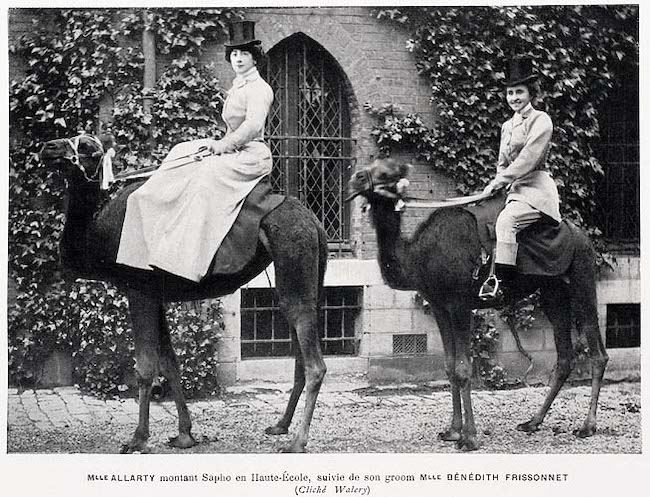

Ernest Molier had always had a penchant for circuses and equestrian events, saying as a child “he would die in the saddle.” This youthful hubris was realized – by the age of 25 Molier had become an accomplished horseman. Everyday he practiced dressage from home and trained pupils. Molier went on to train not just horses but also dogs, monkeys, geese, and even camels. Molier had always been a bit of a dilettante but at the age of 36 his childhood dream of joining the circus became a reality. With the aid of his upper crust volunteers, he became a circus impresario – an unusual career choice for the son of a treasurer and magistrate.

Molier’s original makeshift circus was a rudimentary wooden structure that enclosed the riding stable located at his home on the Rue de Bénouville. The structure included a circus ring of the standard 13m, the same as a professional circus. Accommodating around 400 people, the Cirque Molier was accessed via one narrow entry and the loges could only be reached by the means of ladders, removed once the final spectator was seated.

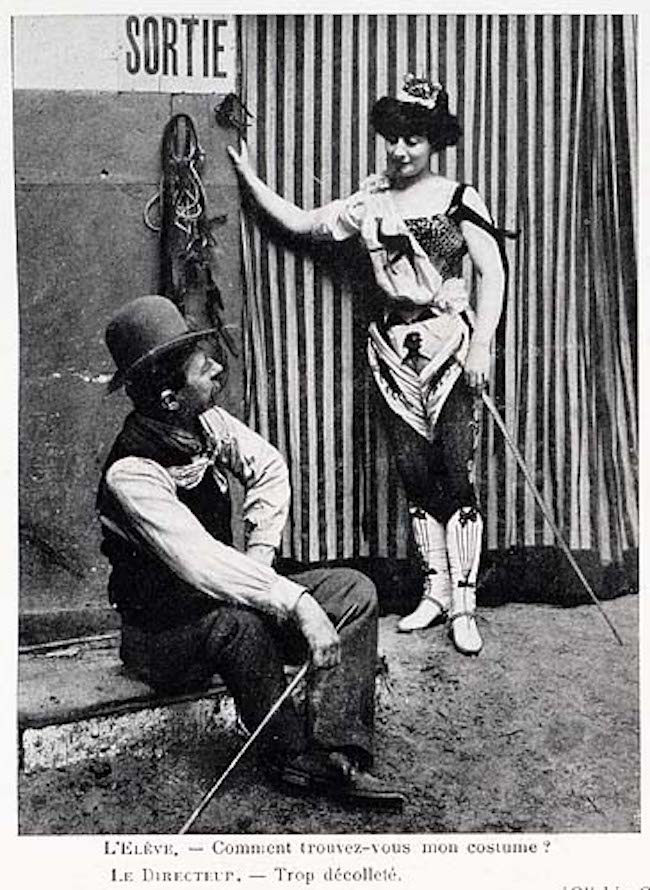

Molier’s first circus performance took place on March 21, 1880 with Molier himself entering the ring on a Percheron mare. The event was by invitation only but aristocrats soon clamored to be included. The crowds were made up of the gratin of society. Actresses and female performers had their own nights to witness the circus, a rehearsal of sorts, so they wouldn’t have to rub shoulders with the upper class darlings. Giving one double set of performances per year, Molier’s circus reached both the aristocratic set and the world of entertainers, sealing both groups’ love of the circus.

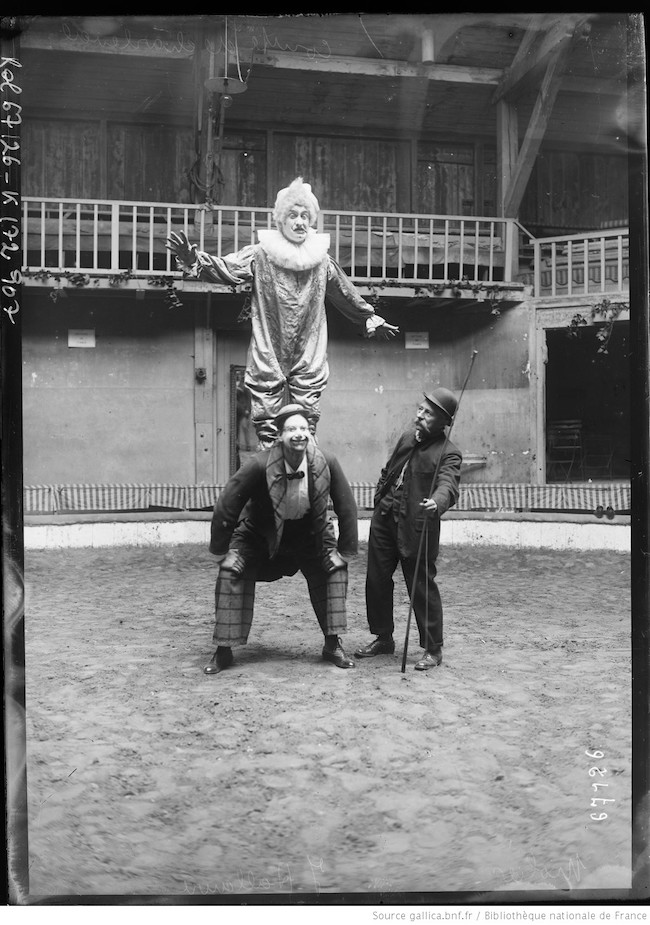

Molier’s society friends could exhibit their alter egos at his circus, readily becoming clowns, trapezists, and equestrian stars at the set of annual performances. Ernest Molier listed his friends on his program: M. Vasseur was a fencer, M. Wagner would be a gymnast, Van Husen would play Hercules and Dr. Laburthe would wrestle and throw weights. The pantomime was well performed by the painters Gerbault and Adrien Marie. Counts, barons and lieutenants would be the equestrians. While most of these names mean nothing to us now, this would be akin to the House of Lords leaping about in a carnival setting. Even the front of house staff was comprised of “gentlemen.”

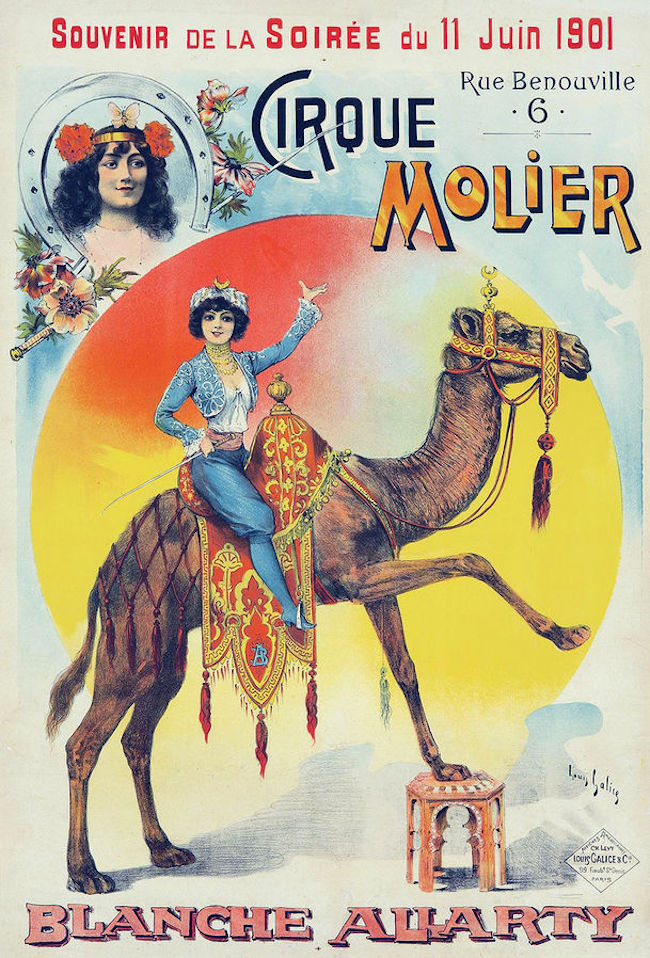

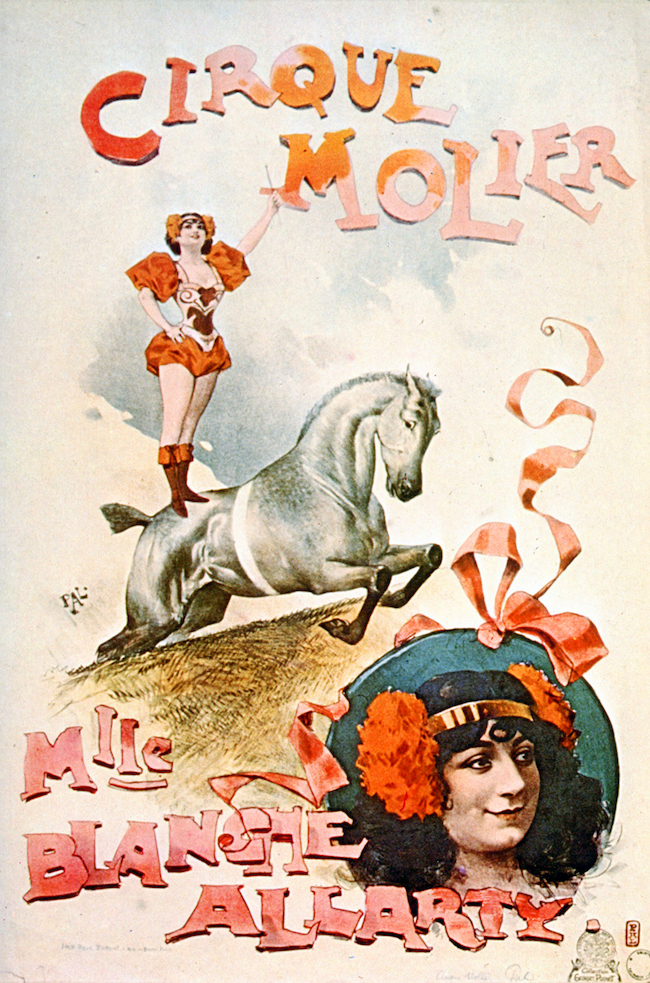

Poster by Pal (Jean de Paléologue, 1855-1942) for the Cirque Molier, featuring Blanche Allarty (c.1895) History: [[Cirque Molier]]. Photo credit © Circopedia.

Baron de Vaux in his 1893 history of European circuses observed that “the saltimbanques and the clowns who perform once or twice a year for the Parisian high life, are not at all like those at the Hippodrome. These are young men from the best circles of society who wanted to ‘launch’ a new kind of sport, and who succeeded: they have been conscientiously working and, after several exercises are able to compete with real equestrians and clowns. I can mention among them: Count Hubert de la Rochefoucauld.”

From his perch on a trapeze, the monocled gymnast in James Tissot’s 1885 painting Women of Paris: The Circus Lover is Hubert de la Rochefoucauld. Presumed to be the Cirque Molier, Tissot used his artistic license to depict a fashionable audience in a small and elegant theater watching their own kind perform as clowns and acrobats. The artist attempted to recreate the titillation that must have been felt by the predominantly female audience in such close proximity to the nearly naked aristocrats. Rochefoucauld performed at Molier’s circus either on the trapeze or parallel bars at each soiree on record from 1880-86. After that, names did not appear on the programs.

Women of Paris- The Circus Lover by artist, James Jacques Joseph Tissot. Photo credit © Google Art Project, Wikimedia.

An account of Molier’s circus included this about Count Rochefoucauld, “Hubert was so determined to imitate Leotard, (he of the flying trapeze and one piece gym suit) that vaulting and athletic exercises became such a great occupation of his, that his chateau in Choissy was adapted to contain a gymnasium.”

In another 1893 recounting found in the San Francisco Argonaut, author Sibylla states in her article “An Amateur Circus in Society” that the women in attendance, “bestow their most flattering applause to the gentlemen acrobats and riders. The Count de Rochefoucauld, above all, exceedingly handsome in his green silk tights, carries off a majority of the votes.”

“It was the ambition,” Sibylla continued, “of all the fashionable youth to belong to the Cirque Molier.”

In 1904 Hubert would take part in a duel with Count Vares near the Eiffel Tower which would wound Vares badly in the thigh. Hubert de Rochefoucauld was a competent painter in his own right.

It was not the women of the upper echelon who made up the quota of female performers, although certain masked society women did appear. Professional equestriennes, many of whom Molier had trained himself, were hired. The best, the fearless Blanche Allarty, became Molier’s wife. Although by no means professional, Molier is said to have hired the very young Suzanne Valadon, who at the time was known as Marie-Clémentine. The fiercely independent artist’s model and painter claimed to have worked on the trapeze for six months until a fall ended her juvenile career.

Even though the performances at the Cirque Molier were few and far between, the Molier had an impact on the Parisian social scene and its competitors. The circus had its detractors in the Parisian press who deemed it unseemly for the nobility to display themselves as buffoons, but the press always covered the events at the Molier with full page illustrations and commentaries.

Molier went on to present up to three galas per year. In 1898 he expanded into a more spacious arena. For 53 years until the death of Molier, the show went on. The last performance took place in 1933. Molier was 90 and suffering from a dislocated shoulder but took part nonetheless. He died a month later in his home on rue Bénouville.

Blance Allarty on D’artagnan Cirque Molier 1911. Photo credit © Circopedia.

Lead photo credit : Cirque Molier. Photo credit © Toronto Public Library

More in 19th century, circus, circus in Paris, entertainment, performance art