The Artistry of Time: A Tour of Intriguing Sundials in Paris

If we look back at Paris’s history, there are innumerable examples of science and technology coalescing with art and aesthetics, exemplified by gems such as Foucault’s Pendulum, Blaise Pascal’s statue at Tour Saint Jacques and even the Eiffel Tower itself. In case you didn’t know, the tower, which is today equated with love and romance, was once used to conduct meteorological and astronomical observations and even used as radio antenna and optical telegraph. (Radio and digital television signals are still broadcast from the tower.)

One often overlooked aspect of the Parisian cityscape that delightfully evokes how art and science inhabit the same cultural space? The city’s collection of sundials. These intricate timepieces have been a part of Parisian façades for centuries, each one telling a unique story about art, architecture and astronomy.

I would like to share a few of these remarkable sundials in Paris, and bring you some snippets of their history.

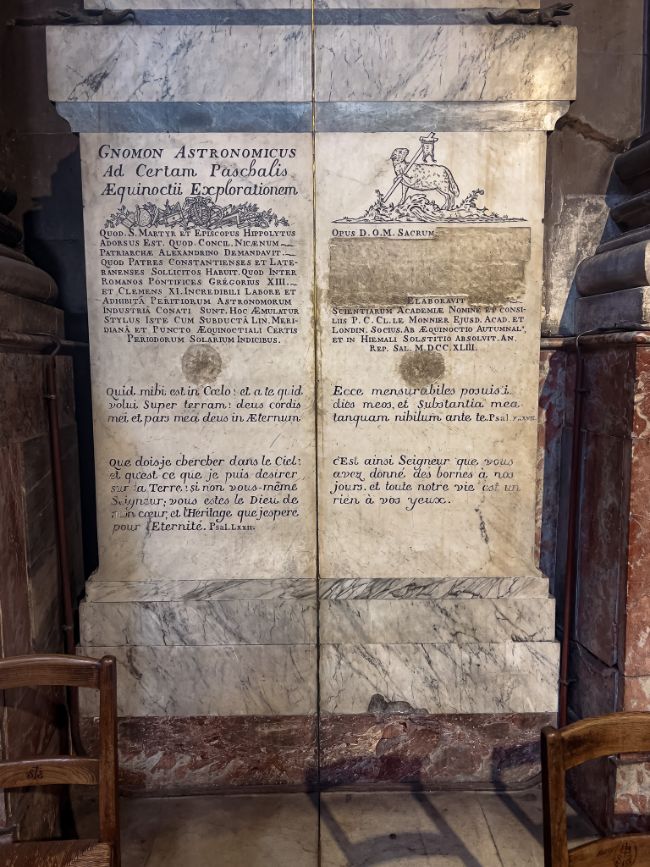

Gnomon de Église Saint-Sulpice

Right in the heart of eclectic Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the Saint-Sulpice Church is hard to miss. With a beautiful square in front, the church combines architectural influences from Italy and France, adorned with paintings by imminent artists such as Eugène Delacroix (1861), who painted murals in the Chapel of the Holy Angels.

Gnomon de Eglise Saint-Sulpice. Photo credit: Pronoti Baglary

If you observe the floor of the church, you will notice that a meridian line- following a north-south axis- splits the transept. (This is the intersection between the nave and the choir, giving it the shape of a cross in traditional Romanesque and Gothic architecture.) Interestingly, astronomical devices such as these are not uncommon in French churches, standing testimony to an era in history when churches served both as spaces of religion and science.

Gnomon de Eglise Saint Sulpice. Photo credit: Pronoti Baglary

The sundial here was built under directions of Jean-Baptiste Languet de Gergy, a parish priest between 1714 to 1748. It’s incredible due to its intricacy and size. Composed of an obelisk with a brass ruler inserted in the middle, the sundial continues onto the floor, representing the meridian line of Paris.

A tiny lens in a stained-glass window in the southern end of the church lets sunlight enter and form a small disk of light on the floor, indicating noon when it crosses the meridian line. (It can also be used to determine the solstice and equinox.) The obelisk acts at the gnomon, which refers to the part of any sundial that projects or juts out, with the gnomon’s shadow helping indicate time. Though it is not used anymore, the sundial is still functional.

Address: 2 Rue Palatine, 6th arrondissement

Gnomon de Eglise Saint Sulpice. Photo credit: Pronoti Baglary

Église Saint-Eustache

In a similar vein, the front façade of Église St. Eustache features two sundials, one atop the circular window, which is traditionally called a “rose window,” and the other a little lower down to the left.

Saint-Eustache Church. Photo credit: Pronoti Baglary

The story goes that astronomer Pierre Charles Le Monnier (1715 – 1799) would use these sundials to adjust his telescope. His astronomical calculations using the sundials of Eglise Saint-Eustache were instrumental in some of his most significant findings. Incidentally, he was also the designer commissioned for the aforementioned Gnomon de Église Saint-Sulpice.

Address: 2 Imp. Saint-Eustache, 1st arrondissement

Luxor obelisk at Place de la Concorde

Any visitor to Paris has walked across the enormous square that is Place de la Concorde. With the magnificent Hotel on the Marine on one side and the stunning Seine on the other – not to mention the sweeping view of the Champs-Élysées – this square probably sees more footfalls than any other in France.

Luxor obelisk. Photo credit: Pronoti Baglary

However, most people do not realize that the Place de la Concorde is home to one of the largest sundials in the world: the ancient Luxor obelisk from ancient Egypt. Situated in the very center of the square, the obelisk was a gift in 1830 from the Sultan and Viceroy of Egypt Mehemet Ali to King Charles X.

Luxor obelisk. Photo credit: Pronoti Baglary

Originally part of a pair of obelisks marking the Luxor Temple in Thebes in the reign of Ramesses II, it measures 22 meters high and weighs 220 tons. The obelisk acts as a gnomon that indicate the hour of day, and it also has solstice curves, the equinox and hour lines carved on it.

Address: Pl. de la Concorde, 8th arrondissement

Le canon méridien du Jardin du Palais Royal

Tucked away behind the busy Rue Saint-Honoré, Jardin du Palais Royal is one of the most beautiful courtyard gardens in Paris, making it a favorite haunt of Parisians. In the middle of the garden, among the stunning magnolia trees, is a tiny little cannon.

This cannon is called le canon méridien, and it was once used to tell time. The cannon was designed by Sieur Rousseau, a watchmaker at 95 galerie de Beaujolais in 1786. And why a canon, you ask? Well, it was because the barrel attached to the cannon was fired every day to indicate the exact hour of “true noon.” On sunny days, a tiny magnifying glass inside the cannon would generate enough heat to burn the wick inside the cannon, leading to it being fired.

Le canon méridien. Photo credit: Pronoti Baglary

This event would attract huge crowds of onlookers. However, once Greenwich Mean Time was imposed on Paris in 1911, the cannon lost its purpose. But it still stands as a testament to a bygone era, reflecting the evolution of humanity’s progress in time-keeping.

The canon seen in the gardens is actually a replica of the original, and it is still fired on a few special occasions such as July 14, Bastille Day (la Fête Nationale) and August 25, the day of the Liberation of Paris.

Address: Palais-Royal Garden, 18 Gal de Montpensier, 1st arrondissement

Salvador Dalí’s sundial

Off a busy street in the Latin Corner, in the corner of a nondescript building, lies a hidden gem in plain sight: a sundial which was designed by the artist Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) himself.

The story goes that the building belonged to a friend of Dalí, and he designed this tiny instrument as a present. Just one look at the sundial will reveal how it bears the trademark surrealist quality of Dali’s artistic oeuvre.

Salvador Dali’s sundial. Photo credit: Pronoti Baglary

The sundial depicts a face in the form of a scallop with blue eyes and flames emanating from the eyebrows. Hair cascades down the shoulders in a way that any Dali lover would recognize: in the shape of his famous twirled mustache.

The scallop design is a clever reference to the name of the street Rue Saint-Jacques, which refers to the scallop shells worn by the pilgrims walking this street on the Saint James Way. (The pilgrimage route continues all the way to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in northwestern Spain.) The sundial also comes with an artist’s signature, leaving no doubt as to its origins.

Address: 27 Rue Saint-Jacques, 5th arrondissement

Next time you walk around Paris, I hope you don’t forget to look up and spot hidden sundials, making discoveries of your own. There are many of them strewn across the capital, inspiring a veritable treasure hunt across the arrondissements.

Lead photo credit : Saint-Eustache Church. Photo credit: Pronoti Baglary

More in Gnomon de Église Saint Sulpice, Le canon méridien, lise St. Eustache, luxor, Luxor obelisk at Place de la Concorde, Palais Royal, place de la concorde, sundials

REPLY