The Paris Cook Club: Vive La Differénce!

The Paris Cook Club, now socially-distanced, is comprised of various nationalities: American, English, Irish, and Belgian. As long-time residents of France, we are fluent in French and English and finesse recipes in both languages. During the pandemic we have been preparing dishes keyed to a theme: Each cook selects her preferred fare and recipes and shares the results online. This approach has highlighted our diverging culinary paths, which stem mostly from our backgrounds.

The cooks. Photo credit © Paris Cook Club

When the theme of Indian curry was selected in November, it became evident that nationality leaves marked imprints on one’s tastes. The Americans were not very enthusiastic, unlike the Belgian (married to an Englishman), English, and Irish cooks. In the 18th century, British bureaucrats and traders who had spent time in India lumped all the savory, spicy food into something called “curry.” Then the Brits blended together the spices – coriander, cumin, ginger, turmeric – to make “curry powder.” The most popular preparation – chicken tikka masala – was named a British national dish in 2001.

Some of the curry-loving members of the Paris Cook Club made butter chicken, where the bird is cooked in a tomato, butter, and cream sauce much like tikka masala. Others undertook more complicated Indian specialties: chicken biryani (a meat and saffron rice curry) and lamb raan (marinated lamb originally made with goat). The non-believers remarked that these creations all looked and tasted alike. This split also appears when the American comfort food of spaghetti and meatballs is contrasted with English spaghetti Bolognese or “Spag Bol,” which the Brits transformed from the Italian dish of tagliatelle al ragu.

Chicken curry. Photo credit © Paris Cook Club

Scotch eggs, pickled walnuts, and bread sauce are to be found on British holiday tables, but are unknown in the USA and France. Just as the French don’t appreciate the uniquely American holiday of Thanksgiving. As written by humorist Art Buchwald in his famous Washington Post column “Le Jour de Merci Donnant,” this is the only day of the year when Americans eat better than the French. But cornbread, candied sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce, and pumpkin pie are too peculiarly sweet for the Gauls. And trying to find une dinde (a turkey) in France in November is a challenge since the birds are reserved for Noël. This year, one butcher claimed all the turkeys were in “confinement” (coronavirus lockdown) until the end-of-year holidays. But the French did adopt Black Friday and extended the soldes (sales) indefinitely to spur holiday shopping.

Pumpkin pie. Photo credit © Paris Cook Club

On the Réveillon (Christmas Eve), the French sit down with their families to a long repast (up to six hours) that’s sure to include huitres (oysters), saumon fumé (smoked salmon), foie gras (the fattened liver of a goose or duck), turkey with chestnuts, and la Bûche de Noël (traditionally, cake decorated like a yule log). In Provence, the tradition is les treize (13) desserts (including fruits, nuts, and sweets) symbolizing Christ and the 12 disciples. Christmas Day is generally for les restes (leftovers). More oysters and foie gras with lots of champagne are consumed on Saint Sylvestre (New Year’s Eve).

Foie gras is enjoyed by most of the Paris Cook Club, but some object to the gavage or force-feeding of the birds. The classic way of serving foie gras at Christmas is on pain d’épices (similar to gingerbread but less sweet) with confit d’oignons or confit de figues (onion or fig jam). We cooks have experimented with foie gras – searing it whole, processing it into paté, melting it into a sauce, or pureeing it into a mousse. Our coffee menu featured a cappuccino of foie gras while macarons and crème brulée are sugary treats which can be made with this delicacy. The partner drink is Sauternes whose sweetness complements the creamy richness of the liver.

Foie Gras mousse. Photo credit © Paris Cook Club

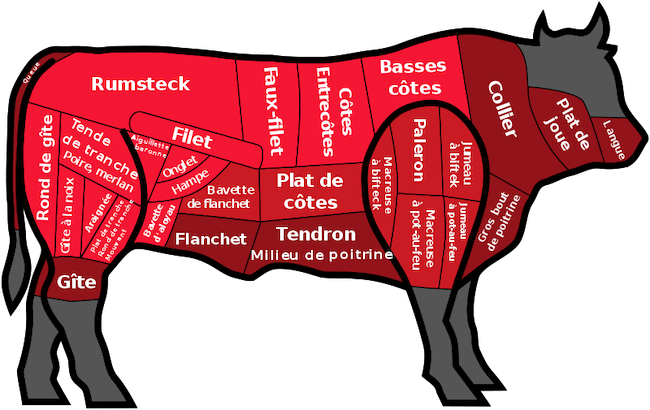

When preparing English or American meat dishes, the Paris Cook Club is often befuddled by the butchering practices of France. A flank steak to Americans is a skirt steak to the English and a bavette to the French. Sirloin in London is strip steak in New York and faux-filet in Paris. Not only are the terms different, but butchers vary significantly by country in their carving-up methods. The English and Americans cut their beef into about 40 cuts while the French go for more than 100. There are marked divergences in the sub-division of primal cuts and the hindquarters are carved at varying angles — one reason British and American steaks are more tender than their French counterparts.

Common cuts of beef in France. Brighter colors show higher valued parts. Photo credit © Brazilian_Cut (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Pork and lamb are butchered in similar ways in these countries. However, there are some Anglo-American holiday specialties, such as gammon or Virginia ham, which cannot be found in France. To compensate, we substitute an entire boiled ham from the deli (meant to be sliced for sandwiches) and bake it with a sweet glaze. Bone-in, skin-on chicken breasts are rare in France; the closest substitute is suprême de volaille which is a breast with skin and wing attached. The French cook mainly with boneless skinless chicken breasts or they brown hauts de cuisse (chicken thighs).

Adapting and adjusting recipes to account for national differences adds to the cooking challenge, especially around the holidays. American Christmas cookies (called biscuits by both the English and French) must be made with a reduced amount of butter (or more flour) to account for the higher fat content of the spread in France. To accompany the turkey, the English perfect their roast potatoes while Americans mash and the French bake gratin dauphinoise (scalloped potatoes). The holiday feast culminates with mince pies and plum pudding in the U.K., chocolate chip cookies in the U.S., and the traditional bûche in France – all delicious. Vive la différence!

Recipes: American Cornbread and Holiday Cutout Cookies

Want to be inspired by more French foodie experiences and enjoy classic French food, wine and recipes? Head to our sister website, Taste of France, here.

Lead photo credit : Photo credit © picjumbo.com, Pexel

More in cooking at home, cooking club, Paris cooking class