A Gift from the Gods: The History of Chocolate, from Mesoamerica to Paris Boutiques

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The history of chocolate, and its circuitous route to Paris, is not for the squeamish. From human sacrifice to the infamous Spanish Inquisition, the growing and harvesting of cacao seeds for the production of chocolate has tortured, enslaved, and seduced.

The cacao tree was not domesticated in Central America as previously thought. Traces of cacao from a variety currently prized by the world’s chocolate industry were recently found in pottery jars by Ecuadorian and French archaeologists. Unlike the sweet bonbons we are used to indulge in today, the Mesoamericans consumed cacao, or “xocoatl” (bitter-water), 5,500 years ago in Ecuador’s Amazon region. They believed it was the “food of the gods.” The unsweetened drink — made from the seeds of large, melon-shaped pods that grew on the trunk of the tree — were ground and mixed in hot water with spices, berries, and herbs.

The cacao (C) Rodrigo Flores, Unsplash

Over centuries, the prized seeds were used in all facets of life: nutritional, medicinal, spiritual and financial. They were traded among the indigenous peoples, first to the Olmecs (1500-400 BC), who lived in the tropical lowlands of the Gulf of Mexico, then to the Mayan people (1500 BC-1000 AD) who inhabited the Yucatan peninsula, and finally to the Aztecs (1400-1521 AD) who ruled central and southern Mexico. Cacao was a symbol of abundance; it was a divine food, health elixir, and aphrodisiac – the gift of the Mesoamerican deity, Quetzalcóatl, the serpent god who created the cacao tree for humans.

The first Europeans to encounter cacao were Christopher Columbus and his crew members on their fourth voyage to the New World. Arriving in what is present-day Nicaragua in 1502, Columbus was unimpressed by the “…curiously spicy and bitter drink…”, and misunderstood the importance of the plant’s use as a profitable crop. It was the Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés, known for his murderous conquest of Mexico on behalf of King Charles V (King of Castile and Aragon), who realized its potential value.

Christopher Columbus (C) Sebastiano del Piombo, Public Domain, Wikipedia

During the time Cortés spent in the capital of Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City), he discovered cacao beans were used as the primary form of currency in the Aztec world: 100 cacao seeds purchased a slave, two hundred cacao seeds bought a male turkey, and 10 bought the services of a prostitute. At the time, Tenochtitlan was the largest city in the world, and it held the bounty of a vast and powerful empire. In addition to the gold and other riches Cortés looted, he found enormous stores of cacao beans. Indeed, there may have been as many as a billion cacao seeds in the royal treasury at one time.

Cortés soon realized that cacao seeds held a much greater societal importance. He witnessed a grisly ceremony in which Aztec priests, using razor-sharp obsidian blades, sliced open the chests of sacrificial victims and offered their still-beating hearts to the gods. The blood of the victims was then mixed with xocoatl and imbibed by the elites, symbolizing the circle of life and death. As hard as it is to imagine, many captured soldiers, slaves and Aztec citizens went willingly to the sacrificial altar offering their hearts to their sun god, Huitzilopochtli. It was an honor and a guaranteed ticket to a magical afterlife.

Obsidian (C) Ji-Elle, (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Upon returning to Spain in 1528, Cortés presented King Charles V with what he called “chocolatl,” along with the recipes for its preparation. Duly impressed, the chocolate drink quickly became the favorite of royalty. It also was tied to a different kind of magic — the magic of making money, which now, literally, grew on trees. Cacao, easily mispronounced as “cocoa”, when mixed with other colonial imports, like vanilla, cane sugar, nutmeg, and cinnamon, became a very profitable crop.

From the Catholic Church’s perspective, however, the absence of a recognizable religion in the Americas meant that its inhabitants must have been under the influence of Satan. This misconception made chocolate’s trajectory from Mesoamerica to the rest of the world anything but smooth. In time, women were accused of being witches and burned at the stake for reportedly casting magical spells with chocolate, or poisoning people with chocolate potions. Ironically, Catholic priests used the high-energy drink to sustain themselves during religious fasts. For close to a century, Spain kept the secret of cocoa beans hidden, restricting their processing exclusively to monks cloistered in Spanish monasteries.

An Aztec woman generates foam by pouring chocolate from one vessel to another in the Codex Tudela (C) Unknown, Public Domain

Most history books claim chocolate was introduced in France at the wedding of Louis XIII and Anne of Austria in 1615, but this simplistic telling of the story conceals the truth of its origins. Chocolate actually first arrived in France from Spain, brought by Spanish and Portuguese Jews fleeing the Inquisition. By 1550, they settled in the Saint-Esprit district in Bayonne, on the right bank of the Adour River. As “Marranos” (new Christians), these Jews were granted rights of residence by local authorities. Importing the tools and knowledge of cocoa, Bayonne’s Marrano Jews taught local workers the secrets of processing chocolate. Resenting their success, the local workers created a chocolate makers guild which prohibited Jews from working in the chocolate trade. This anti-Semitic restriction wasn’t rescinded until 1767.

Apart from the Spanish, merchants from other parts of Europe (Italy, France, Holland, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria) started to visit Central America in search of cocoa beans, recognizing their value. It wasn’t until Ann of Austria, daughter of Philip II of Spain, introduced the beverage to Louis XIII that chocolate entered the gastronomic lexicon of French society. In 1643 the Infanta of Spain married Louis XIV of France in the Basque fishing village of St. Jean de Luz, not far from the city of Bayonne. She gave her Louis an engagement gift of beautifully wrapped chocolate.

Chocolate was extremely popular with the Sun King, Louis XIV, and members of his court. He liked chocolate so much that he ordered it served in the Palace of Versailles on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays. He also appointed a nobleman named David Illou to create and sell chocolate. Art and literature soon abounded with erotic imagery inspired by chocolate, and its reputation as an aphrodisiac flourished in the French courts. Louis reigned for over 74 years (1643 to 1715), and it was well known that in his 72nd year he was making love to his wife twice a day!

Louis XIV of France (C) Hyacinthe Rigaud, Public Domain

In 1659, King Louis XIV gave the title of Chocolatier du Roi to David Chaillou, an officer of the queen, granting him the sole privilege of manufacturing and selling chocolate. Two years later Chaillou opened a boutique at the corner of rue de l’Arbre-Sec and rue Saint-Honoré in Paris, where the wealthy could purchase the “food of the gods” – and kings. Chaillou’s monopoly as the only chocolatier in Paris lasted 29 years.

By the time Louis XV ascended the throne, chocolate had already seduced the Parisian nobility. Madame de Pompadour — his friend, advisor, and would-be lover — was advised to mix chocolate with ambergris (whale sperm) to overcome her frigidity, and stimulate her desire for the king. She became his lover from 1745 until her death in 1764. Louis V also made hot chocolate for himself in the kitchens of his private apartments to enhance their sexual relations. His recipe has survived the centuries. (See the bottom of the article for the exact text!)

Madame de Pompadour (C) Charles-André van Loo, Public Domain

In 1780 that the royal privilege of making chocolates was revived when Chaillou’s great-great-grandson, Sulpice Debauve, King Louis XVI’s pharmacist, became Queen Marie-Antoinette’s official chocolatier. He created the first chewable chocolates mixed with cocoa butter and medicine, after Marie Antoinette complained to him about the unpleasant taste of the remedies she took for migraines. The queen was so pleased that she named those exquisite medallion-shaped chocolates, pistoles. Debauve continued to create a variety of flavored pistoles for the Queen.

In 1800 Debauve opened his first chocolate shop on the Rive Gauche. In 1823, along with his nephew, Jean-Baptiste Auguste Gallais (1787–1838), they created dietary chocolates, known then as “healthy chocolates.” They were made with almond milk, vanilla and orange blossom water. In 1819 the company received the royal warrant as purveyors to the French court, later named the official chocolate supplier for Emperor Napoleon and of Louis XVIII, Charles X and Louis Philippe.

Sulpice Debauve died in 1836, followed by his nephew in 1838. Their business was acquired by Nicolas-Eugène Hugon. In 1857 he built a factory powered by a steam engine, located in the seventh arrondissement of Paris. He was awarded a bronze medal at the Universal Exposition of Art and Industry of Paris in 1867. His son Gustave took over the company in 1873, raising Debauve & Gallais to one of the finest French chocolate brands. Hugon was awarded a silver medal at the Universal Exposition of Paris in 1878, and a gold medal at the Universal Exposition of Antwerp the same year, for “flash chocolate,” chocolate granules for making instant hot drinks. Other gold medals were obtained at the Universal Expositions of Paris in 1889 and 1900. Later, the shop and the factory became managed by Hugon’s sons, Maurice and Georges. In the 1930s their respective sons, Jacques and Robert, took over the business. Debauve & Gallais, located at 30 Rue des Saints-Pères, is still family owned and operated.

Benjamin Gavaudo (C) Public Domain

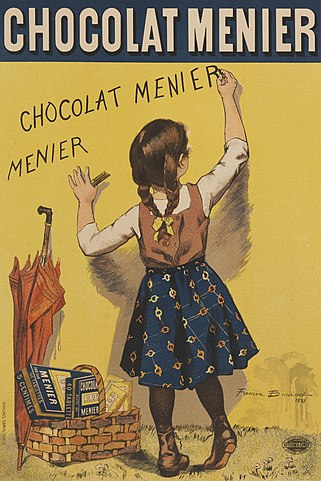

As chocolate became affordable for the masses, the Menier chocolate company was founded in 1816. Jean-Antoine Brutus Menier ran a pharmaceutical company in Paris. Although not trained as a pharmacist, he sold a number of different powders for medicinal purposes. He initially used chocolate as a covering for bitter-tasting pills. It became so popular that by 1830 Menier built a factory in Noisiel which became the mass production factory for cocoa powder in France. In 1836 Menier became the first company to introduce blocks of chocolate which were wrapped in their trademark yellow paper. By 1853 Menier was producing over 4,000 tons of chocolate a year. In 1878 the brand won seven gold medals in the World’s Fair in Paris.

The First and Second World Wars in France took their toll on the production and the company. By 1965 the Menier family no longer held interest in the company. The factory in Noisiel was designated by the government of France as an official “Monument historique,” and listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site. It is currently the Nestlé France headquarters.

Chocolate (C) Pablo Merchán Montes, Unsplash

There are a number of talented chocolatiers who create unique creations throughout France. In Paris today, one can find a plethora of small shops selling a variety of bonnes bouches on almost every street corner. Most French cocoa bean imports today come in the form of bulk cocoa from West Africa. Direct imports from Ivory Coast reached nearly 50 thousand tons in 2019.

Sadly, though not surprisingly, almost all cocoa beans today are harvested by children, often slaves, in western Africa. In the Ivory Coast alone, there are an estimated 200,000 children working the cocoa plantations. Human rights organizations estimate that child slave labor is found on at least 90 percent of the Ivory Coast cocoa production. And since about 80 percent of the world’s cocoa supply comes from West Africa, it is likely that almost all the bulk cocoa used by the world’s big chocolate companies is really child slavery chocolate. So it is increasingly important that we buy ethically, sustainably produced chocolate.

To learn more you can visit the chocolate museum in Paris, and even create some chocolates of your own, visit Choco-Story, Musée Gourmand du Chocolat at 28 Boulevard de Bonne Nouvelle in the 10th.

Below are some of my favorite ethical chocolatiers in Paris today.

La Maison du Chocolat:

225 rue Du Faubourg St Honoré, 8th

52 rue François 1er, 8th

8 boulevard De La Madeleine, 9th

19 rue De Sèvres, 6th

120 avenue Victor Hugo, 16th

Pierre Marcolini:

64 rue du Commerce, 15th

boutique at Lafayette Gourmet

235 Rue Saint-Honoré, 1st

89 rue de Seine, 6th

Jean Paul Hévin:

41 Rue de Brétagne, 3rd

231 Rue Saint-Honoré, 1st

3 rue Vavin, 6th

93 rue du Bac, 7th

Boutique at Lafayette Gourmet

Le Chocolat Alain Ducasse:

The manufacture is located near Bastille at 40 rue de la Roquette in the 11th with other boutiques situated throughout the city.

And for a sip of Coco Chanel’s favorite hot chocolate, don’t miss Angelina’s, located at 226 Rue de Rivoli.

Louis XV’s famous recipe:

“Place an equal number of bars of chocolate and cups of water in a cafetière and boil on a low heat for a short while; when you are ready to serve, add one egg yolk for four cups and stir over a low heat without allowing to boil. It is better if prepared a day in advance. Those who drink it every day should leave a small amount as flavoring for those who prepare it the next day. Instead of an egg yolk one can add a beaten egg white after having removed the top layer of froth. Mix in a small amount of chocolate from the cafetière then add to the cafetière and finish as with the egg yolk.” (Dinners of the Court, by Menon, 1755 (BnF, V.26995, volume IV, p.331)

In researching this article, Sue Aran drew from The True History of Chocolate by Sophie & Michael Coe

Lead photo credit : Chocolate (C) Tetiana Bykovets, Unsplash

More in best chocolate, chocolate, chocolate in Paris