How Gabrielle Chanel Reinvented Fashion and Liberated Women

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

On October 1st, Palais Galliera, the fashion institute of the city of Paris, reopened after a two-year refurbishment with a retrospective dedicated to Gabrielle Chanel, in one of the few highlights of an otherwise subdued Paris Fashion Week.

While it was hard for me to put aside the unsavory details of Coco’s life (notably, how she cozied up to the Nazi occupiers), as I explored the show the beauty of the displayed garments allowed me to put my reservations on her persona aside, and look at her visionary talent instead.

The curators of the exhibition (Miren Arzalluz, director of Palais Galliera, and Véronique Belloir, with the help of fashion historian Olivier Saillard, who also curated the Alaïa and Balenciaga exhibition currently on at Association Alaïa) have managed to put together a stunning show that follows the evolution of le style Chanel under the direction of Mademoiselle.

Bias cut. Photo © Sarah Bartesaghi Truong

Covering the period from her beginnings as a milliner, opening a small shop on Rue Cambon in 1910, to her death in 1971, the show is a tribute to how Coco Chanel, a fiercely independent woman, invented a kind of fashion that liberated women, as she advocated for women to live their lives to the fullest.

Heavily borrowing inspiration from men’s closets, Chanel designed garments that allowed women to move freely, practice sports, drive cars, party hard and still look impeccable.

Her formative years in a convent shaped her color choices, and the show is a symphony of whites, beiges and blacks. Chanel’s black was not the color of mourning, but that of evening gowns and parties. In a country where the Great War had erased a whole generation of men, leaving a ratio of one man to four women in the early 1920s, Chanel chose her side: it would be the crazy nights out, dancing until the wee hours, a glass of champagne in one hand and a cigarette in the other.

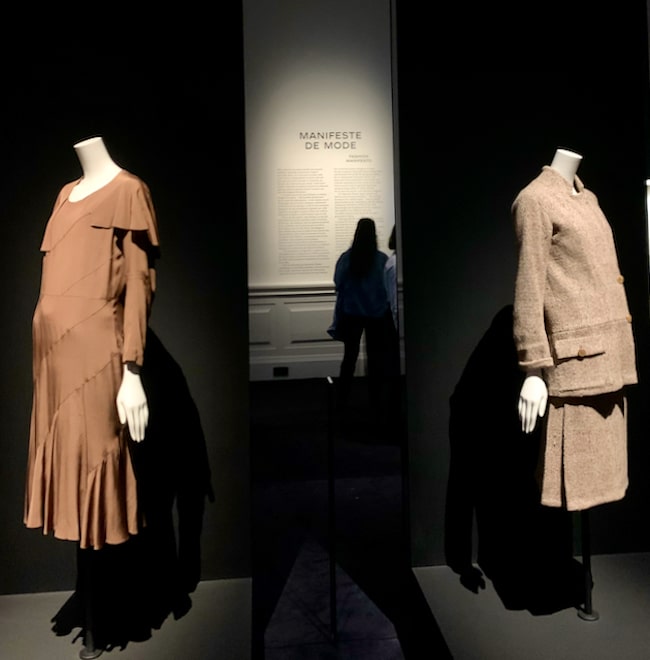

As the Roaring Twenties came crashing down in 1929, fashion adapted to the new economic and political climate. Even Chanel succumbed to the diktat of figure hugging gowns, imposed by the newly fashionable biais cut. Most of all she gave in to what many women felt was a step backwards for their freedom: a whirlwind of outfit changes from day to night, that left little of the insouciance of the flappers.

Flapper fringes. Photo © Sarah Bartesaghi Truong

When the dark clouds of the war shrouded Paris, Chanel closed her maison. It would take the arrival of Christian Dior’s New Look in 1947 to spur Mademoiselle back into action. The cinched, corseted waists accompanied by full skirts, as impractical as they were visually pleasing, reminded her too much of the kind of fashion constraints she had already fought against in the 1910s.

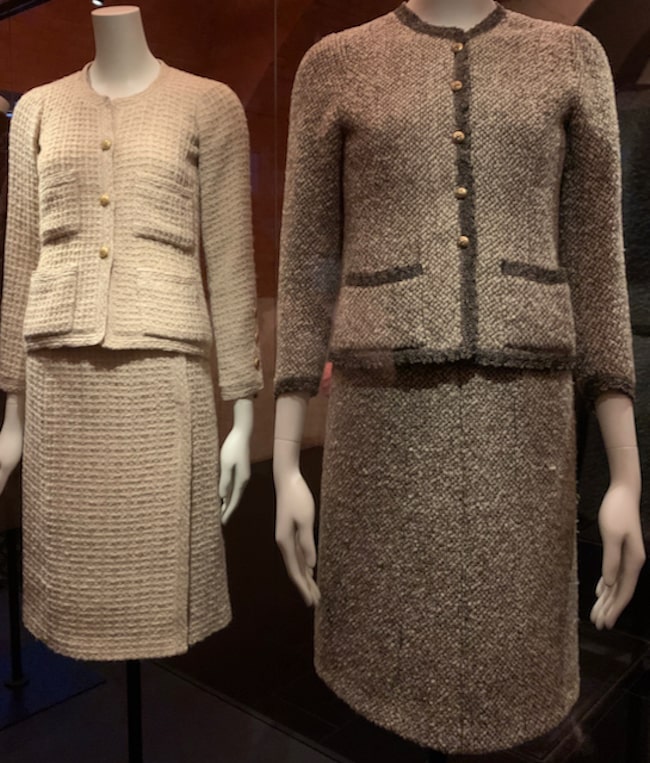

In 1954 her return was frowned upon by many. Her female suits judged to be too plain, the French press chastised Mademoiselle, saying she was too old and a bit passée. But her collection sold well, as it fitted perfectly the active life that women had enjoyed during the war (as they joined the workforce in droves while the men fought at the front) and aspired to carry on.

It took the recognition of Life magazine, followed by other positive reviews in the American press, to catapult Chanel to the forefront of fashion once again.

Looking at these suits with today’s fashion sensibility, it would be easy to dismiss them as stuffy. But when one stops to look at the details, it is easy to understand why women loved Chanel. Her suits were not only comfortable, they were practical: The buttons and the pockets were real, the shoulders were cut very high to afford greater ease in movement, the gold chain stitched inside the hems of the jackets and the skirts made sure that the garments always fell perfectly.

Her accessories also celebrated women as independent: no complicated fastenings or clasps that would require the help of a maid, but long necklaces that could simply be slipped on. And the bold choice of costume jewelry over high jewelry, in contrast with the preciousness of haute couture, is also telling: Men bought diamonds for their wives and lovers, but women purchased their own costume jewelry.

Byzantine inspiration, costume jewellery. Photo © Sarah Bartesaghi Truong

The clothes on display, most of the them coming from the heritage collection of Chanel (sponsors of the show and of the museum’s refurbishment) are breathtaking and impeccably preserved. From a priceless hat from the early 1910s to a sequinned pant-suit created for Diana Vreeland, from feather-incrusted coats to Byzantine-inspired necklaces, to finish with the sparkly lamé evening gowns from her farewell fashion show in 1971, Gabrielle Chanel seemed able to draw her inspiration from everything– her youth spent in a convent, the coterie of avant-garde artists she frequented or medieval artifacts from the Musée de Cluny –to create a style that was unique. Throughout her career, she remained faithful to her vision of the woman she designed those fabulous garments for: a refined, undoubtedly wealthy client, but most of all, someone who chose to live a full and independent life.

These dreamy clothes also tell the story of a less-than-perfect woman, determined to forge her own path in life, free from the social constraints of her time, thanks to an iron-clad determination and an undeniable talent.

Merci Mademoiselle.

“Gabrielle Chanel, Fashion Manifesto” is on at Palais Galliera until March 14, 2021.

Lead photo credit : Coco Chanel exhibit in 2020. The vaulted galleries at Palais Galliera. Photo © Sarah Bartesaghi Truong

More in Coco Chanel, designer clothes, fashion, Palais Galliera

REPLY