Paris Noir: Interview with David and Joanne Burke

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

PARIS NOIR SHORT TRAILER from joanne burke on Vimeo.

David and Joanne Burke are an award-winning filmmaker/writer couple who moved to Paris in 1986 after establishing stellar careers in documentary film and television journalism in New York. Joanne’s credits as a film and video director/producer/editor include more than 20 long-form documentaries on a variety of social, political and cultural topics for CBS, NBC, PBS and HBO. David’s credits include work as a writer/producer with Walter Cronkite, Charles Kuralt, Dan Rather and Ed Bradley. He is the author of Writers in Paris: Literary Lives in the City of Light, and creator of “Writers in Paris Walking Tours,” designated as among the top 10 literary walking tours worldwide by Lonely Planet. Joanne and David’s latest work, a one-hour documentary film titled Paris Noir: African-Americans in the City of Light, was released in 2016, and was followed this year with the book, When African Americans Came to Paris: A Film Companion. The Burkes will be the featured speakers at Adrian Leeds’s Après Midi meet-up on Tuesday, December 12. David and Joanne recently took time to answer Janet Hulstrand’s questions for this exclusive interview with Bonjour Paris.

Janet Hulstrand: First of all, congratulations on the release of your film, Paris Noir: African-Americans in the City of Light. I thought it was wonderful! Can you tell the readers of Bonjour Paris what brought you to this work in the first place? How did you become interested in this subject? Was there a particular moment of epiphany that caused you say “This film has to be made”?

Joanne: How to begin! This has been and continues to be one of the greatest “journeys” of our lives. There is still so much to learn about the contributions African-Americans have made to the world.

I don’t know if there was an actual “beginning.” Dave and I have been lovers of jazz for decades. Interestingly, one of the things that brought us even closer during the time of our courtship was that we found that we had the same record collection. Both of us had been touched deeply by the music: in fact I will go so far to say that there were times that I felt that the music has actually pulled me through rough patches. It continues to be a most important force in both of our lives.

Josephine Baker photographed by Carl Van Vechten, October 20, 1949

Before coming to Paris we had both been privileged to meet some of these amazing musicians-and were even more aware of them as not only creative artists but as warm, generous and caring people, more than willing to share their music and their stories with people who cared. After all, remember, in America jazz had never been considered a true mainstream art form, like ballet or opera.

Coming to Paris 30 years ago changed our lives. We, like most white Americans, knew that Josephine Baker, James Baldwin and Richard Wright had lived and worked here, but that was about it. We also knew that the great pianist/composer/arranger Mary Lou Williams had also spent time in Paris that resulted in life-changing decisions, because we were in the process of finishing up a documentary film about her life and work. That film, Mary Lou Williams: Music on My Mind, was released in France in 1990, and several French TV stations, including Arte, broadcast it.

Mary Lou Williams, by William P. Gottlieb, 1946

One day we walked into Brentano’s and found a book that would move us forward in our thinking about African-Americans in Paris. That was the English version of Michel Fabre’s book, From Harlem to Paris: Black American Writers in France 1840-1980. This was certainly a pivotal moment for us, for we now had a book that documented the full history of Black American writers in France. It is an illuminating and astounding piece of work. We introduced ourselves to Michel and his wife Genevieve, and they in turn invited us to one of the many conferences they had organized at the Sorbonne. At the same time they opened up their vast archive photo collection to us.

During one of the Sorbonne conferences we were introduced to several scholars who were working on the lives of African-American artists who had come to Paris after World War One. We now knew that there were experts who could lead us into the history of the lives of people we had never heard of before—African-American artists who’d managed to get to Paris in the 1920s and 30s, when it was the capital of the art world. This was new and thrilling information.

As we began to wrestle with how to tell this story, Tyler Stovall published his book, Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light. This was also an illuminating moment. Tyler had spent years researching and documenting a story that we were tremendously interested in finding a way to make a film about. We reached out to him, and one sunny day at Café de Tournon, one of Richard Wright’s favorite cafes, he gave us an interview of a lifetime. A natural storyteller, he held us captive for two hours, spelling out in vivid detail the stories of African-Americans in Paris. We were finally on our way to discovering what a huge story we had.

Janet: How long did it take you to make this film? And what kept you going through the monumental amount of work that it took to put it all together?

Joanne: This has been a true labor of love! We never could have imagined that it would take 15, yes, 15! years to complete Paris Noir. Why did it take so long? Well, to begin with, we had no idea that we would find such a complex, rich and somewhat unknown story—especially for white Americans. It was a revelation to be able to learn about James Reese Europe and the soldiers who came to fight for freedom in a faraway country while being denied the same freedom at home. But this was just the beginning of a huge amount of knowledge we had to absorb as naive Americans embarking on truly new path. The more we read, the more we wanted to know. The more we wanted to know, the more we learned. Scholars, artists and tour guides kept opening doors. One thing led to another. We had no budget to travel, so as we heard about scholars coming to Paris we reached out to them. All were more than willing to help us, and they were incredible storytellers as well. One story led to another, one contact led to another. As we gathered the interviews we also began the exhaustive search for material to support the wonderful stories that had been told to us. We needed all the archival footage, photographs, paintings, poems, music, anything we could find that reflected the period. Many years were spent gathering all of this. We worked mainly in film archives in France and the U.S., but also spent vast amounts of time tracking down individual collectors as well as different museums and libraries. Like detectives we were often stuck, but when we finally located a difficult item or previously unknown collector we were elated. Can you imagine what a thrilling moment it was for us when we found actual 1918 footage of James Reese Europe and the 369th Harlem Hellfighter’s Band playing, marching with pride through the French countryside? Thank God someone in command had the great sense to demand or facilitate the filming of this band!

After all that it was more years of sorting through all the material and shaping it, writing and editing again and again until we felt it was right. We feel that we can’t thank enough all the amazing people who helped guide us through this long process.

Janet: Who was James Reese Europe, and why was he important?

Joanne: James Reese Europe was the most well-known African-American musician of his time. Before the war he was known as New York’s leading orchestra conductor, with his 130-member Clef Club Orchestra playing regularly at Carnegie Hall. He’d also been the musical director and hit composer for the world-famous dancers, Vernon and Irene Castle. On top of that, he was an outstanding businessman, finding steady work for Black musicians in and around New York. He promoted his music proudly, declaring, “We Colored people have our own music that is part of us. It is the product of our souls. It’s been created by the suffering and miseries of our race.”

James Reese Europe in 1918. By War Department of the United States [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Janet: How important was Paris in the evolution of African-American history, especially African-American cultural history?

Joanne: Before one talks about the history of African-Americans in Paris, can you imagine what it felt like to be young, gifted and Black in America during the period of Paris Noir? To be disregarded, cast aside, ignored, segregated, brutalized, even lynched? That this was an everyday possibility for African-Americans then—and today, with the reawakening of the white supremacists under the current racist administration. It is a more than horrifying thought. When they came to France, for the first time in their lives African-Americans did not have to fear violence simply by walking down a “wrong” street, or having a coffee with a white person, or booking into a hotel. Here they could eat, dance, socialize, live, love, and move around without the constant threat of losing their lives.

Free at last to develop their talent in a country of white people who were not personally motivated to crush them or their talent, African-American musicians, writers, artists, intellectuals and entertainers flourished. Especially the musicians, who for the first time were paid handsomely. Bricktop, who was hostess of a little club in Montmartre, Le Grand Duc, spoke of having so much cash at the end of the evening that she had to put it in her icebox. While musicians thrived and Josephine Baker continued to thrill Parisians by reinventing herself, the writers and artists struggled to support themselves. Langston Hughes found work as a busboy at Le Grand Duc and soaked up jazz every night, resulting in some of his most lyrical and beautiful poems, including “Jazz in a Parisian Cabaret.” Claude McKay worked as a model and nearly froze to death during the winter months in Paris, but finally made his way to Marseille, where he wrote his powerful novel Banjo.

In Paris, artists were finally free to pursue their talent without restriction. They visited museums, took art courses, and had their work shown in salons and exhibitions, something that was unimaginable in the U.S. at the time. And while most African- Americans returned to a country filled with suspicion and hatred, they carried back with them the seeds of having been truly free in a faraway country filled with white people. And they passed their knowledge on to others. African-American soldiers were able to use their experiences in France as the basis for becoming active in the NAACP and other progressive organizations. Soldiers who went back to life on the farm told the younger generation about their time in France. Richard Wright was one of those youngsters who heard about France from a former soldier, now a Southern farmer. All of the amazing people that we have had the honor to document somehow managed to pass their knowledge onto others. It is more than fair to say that these early pioneers who came to France are now considered some of the founders of the Civil Rights movement.

Janet: What is the most surprising or interesting thing you learned in the process of making this film? Or the saddest, or most poignant?

Joanne: One of the most surprising things we learned was that several African-American women artists lived and worked in Paris during “les années folles.” This was thrilling information. We again have a scholar to thank for this: Theresa Leininger-Miller, who wrote New Negro Artists in Paris: African American Painters and Sculptors in the City of Light 1922-1934. In much of our previous work we have concentrated on helping grassroots women in developing countries tell their stories. Our four-part New Directions series, which was produced during the 1990s, revolves around women from Zimbabwe, Mali, Guatemala and Thailand who not only dramatically changed their own lives but went on to help people in their communities. So we were very committed to finding women scholars to help us tell our story. We also hoped that we would find African-American women artists’ profiles as well. Leininger-Miller’s book helped make that part of our wish a reality.

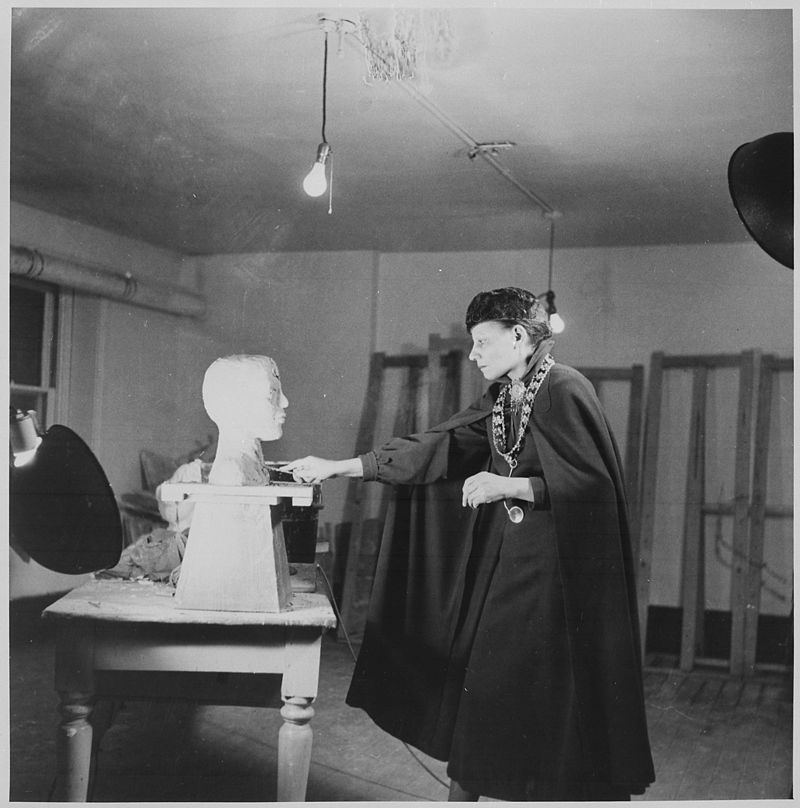

Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

One of the saddest and most poignant things we discovered was the story of sculptor Nancy Elizabeth Prophet. Photographs revealed a breathtakingly beautiful, soulful woman who did some of her most stunning work in Paris. She spent 12 years here, most of it in seclusion and most of the time destitute. At one point she was so hungry that she stole a piece of meat and potato from the bowl of a dog of a French friend she was visiting. To learn about this was heartbreaking enough, but then we found out that even though she found work as an art teacher when she returned to the U.S., she died poor, broke, and unknown by most. But her masterpiece “Congolese” lives on: this gorgeous sculpture was bought by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney around 1931, for the Whitney Museum in New York. A friend of ours recently saw it on display, and was completely struck by its power and beauty.

Janet: It seems only fitting to mention, in this centenary year of the entry of the U.S. into World War I, two other films you’ve produced, one about the Lafayette Escadrille and one about Anne Morgan. Can you say a word about the subjects of these two films?

David: These films were about Americans who joined the French war effort during World War I, before the U.S. became involved. The Lafayette Escadrille was a unit within the French Air Force, composed mainly of volunteer American fighter pilots. Anne Morgan was a daughter of J. P. Morgan: she loved France, and had a chateau at Blérancourt, near Soissons, not far from the front. When the war began, in 1914, she created a military hospital, and got ambulances, and brought more than two dozen American nurses from the U.S. to work here. She was fearless. During the war she had ordered movie film, and she took some outstanding photos, which are in the collection at the Morgan Library.

Janet: Is there a single most important “takeaway” that you hope people will gain from seeing Paris Noir?

Joanne: Dave and I both feel incredibly privileged to have discovered such an important period of (African) American history in a city we both love. To discover, and then to be able to put this project together—even though it took 15 years—has enriched our lives. We feel that we’ve been on a journey, discovering little by little how individuals freed from the hideous confines of racism were able to fully develop their creative gifts. Our hope is that Paris Noir will reach across color, race, and culture, and perhaps help start a conversation with people who don’t know much about this history. These early pioneers have enriched all of us by being brave and bold and courageous enough to take steps to live in a faraway foreign land at a time in history when most Americans were living very provincial lives. The freedom that these artists found in France fortified them emotionally and gave them a vision of the true worth of their work, which is now appreciated in all parts of the world.

Lead photo credit : Mary Lou Williams, by William P. Gottlieb, 1946

REPLY