An Interview with Ellen Hampton, Author of Playground for Misunderstanding

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

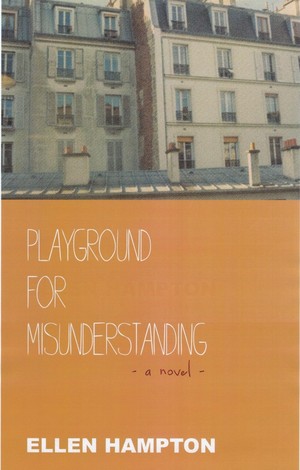

Ellen Hampton, lecturer in history at the prestigious Sciences Po university, and Paris Resident Director for the City University of New York, is the author of Women of Valor: The Rochambelles on the WWII Front, and Playground for Misunderstanding, a murder mystery set in Paris that was released in 2013. Before moving to France in 1989, she worked as a journalist in Miami and Latin America, writing for the Miami Herald, the Miami News, and Cox Newspapers. She recently took the time to discuss her career as a writer and educator, as well as her life in France, with BP writer Janet Hulstrand.

Ellen Hampton, lecturer in history at the prestigious Sciences Po university, and Paris Resident Director for the City University of New York, is the author of Women of Valor: The Rochambelles on the WWII Front, and Playground for Misunderstanding, a murder mystery set in Paris that was released in 2013. Before moving to France in 1989, she worked as a journalist in Miami and Latin America, writing for the Miami Herald, the Miami News, and Cox Newspapers. She recently took the time to discuss her career as a writer and educator, as well as her life in France, with BP writer Janet Hulstrand.

I’ve just finished reading “Playground for Misunderstanding,” and I’m really impressed with the way you’ve created a story that elegantly combines elements of murder mystery, academic farce, Franco-American cultural comparison, and a very sensitive, nuanced portrayal of some of the unresolved social problems underlying the realities of life in Paris today–among other things! How did you have the idea to write this story, or what inspired you to do it? And what were the main issues you wanted to draw attention to, aside from creating a really compelling who-done-it?

I’ve just finished reading “Playground for Misunderstanding,” and I’m really impressed with the way you’ve created a story that elegantly combines elements of murder mystery, academic farce, Franco-American cultural comparison, and a very sensitive, nuanced portrayal of some of the unresolved social problems underlying the realities of life in Paris today–among other things! How did you have the idea to write this story, or what inspired you to do it? And what were the main issues you wanted to draw attention to, aside from creating a really compelling who-done-it?

Thanks! After living in France for 25 years, I finally realized that there would always be a gap of misunderstanding going on, both from my perspective and from that of the French. Up until then, I had thought that if I just spoke French a bit better, if I just learned a bit more, I would succeed in French society. The watershed moment was not being able to find a job at a Paris university after completing my PhD here, not even to teach English! That was when I understood that there were cultural divides that simply would never be bridged, and that it was a waste of my personal capital to keep trying. It led me to thinking about other relationships that are sort of definitively deaf to each other. The male-female thing is always amazing, and as an adjunct professor dealing with 20-year-olds, the older-younger split was fun to explore. Also I was teaching a class in southern culture, and I thought, what would Faulkner write about Paris if he were here today? So a lot of the social issues, and particularly the merging of past and present, came from that angle.

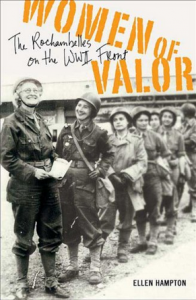

I’m also interested in knowing more about the first book you published, “Women of Valor: The Rochambelles on the WWII Front” (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2006). Can you tell our audience a little bit about who the Rochambelles were, and why you decided to write about them?

I’m also interested in knowing more about the first book you published, “Women of Valor: The Rochambelles on the WWII Front” (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2006). Can you tell our audience a little bit about who the Rochambelles were, and why you decided to write about them?

I met a couple of the Rochambelles at a talk they gave in Paris, and was awestruck. They were a group of French women ambulance drivers organized by an American woman and incorporated into the Division Leclerc during the Second World War. As such, they were not auxiliaries or support personnel, but regular members of an armored division, the only women on the front lines. I interviewed a dozen of them and published their incredible story in the book. For all the immense historiography of the war, they had been overlooked, and now they seem to be getting a lot more attention. There’s even a re-enactment group that dresses up like Rochambelles and goes out on field exercises.

You’re married to a Frenchman, and you have raised your family in France. Your bio describes you as living “on the fault lines of understanding between the French and the Americans.” Can you talk a little bit about what that’s like? Especially about what it’s like to raise children biculturally, in this case half French, half American?

On a personal level, it has been terrific. I’m a military brat, grew up all over the place, which gives you kind of a default outsider status. Though it’s hard to separate that from the outsider stance a writer also takes. I have been extremely lucky to have the loveliest French family ever, even from the start when I didn’t speak more than two words of French. I met my husband when we were journalists in Latin America in the 1980s, and we moved to Paris on a lark, and then never left! I used some of the things I’ve learned from being in a bi-cultural marriage in Playground, particularly the part where you have to explain to your partner what you want, because he is not going to pick up any cues. So in a sense communication is clearer than in the read-my-shoulders kind of thing.

Raising the kids was the challenge it is anywhere, with a double dimension. The kids correct you at the bakery at age 4 when you can’t remember whether a baguette is masculine or feminine (it’s almost always counterintuitive J). I think they appreciate the gift of languages and deeper cultural understandings that come from being an international family.

As an American lecturer at Sciences-Po you’re in a perfect position to observe some of the differences between higher education in France and in the U.S. Can you comment on some of the most significant differences between these two systems, as you see them? What are the pros and cons of each? And how did you and your husband (or how did your sons) decide in which system they would pursue their education?

Sciences Po is a beautiful exception to much of what’s a mess about the French higher-education system, though I hear some changes are underway that may bring improvement. Broadly speaking, I would say that the French system, and this begins in pre-school, pushes too hard for intellectual rigor, without considering that there are other qualities and accomplishments that are also important. You are brilliant or you are nul, and the vast middle tends to get shoved downward. On the other hand, the American system rewards attempt rather than success, which falls short of teaching truly critical thinking, and often results in students who think they deserve good grades for getting out of bed in the morning. So the two systems occupy opposite ends of the pole, and at the Sciences Po Euro-American campus, at least, we try to meet in the middle.

My kids went to the Lycée International in St Germain-en-Laye, one of the first bilingual, bicultural schools in the Paris area. They did the bulk of their courses in French (rigor, criticism), and then history/geography/literature in the American Section (whew! exhale). So they got the balance. All of their classmates had international backgrounds of some sort. I think it’s the coolest school on the planet. Both boys (now 24 and 20) chose to go to American universities. Both discovered when they got there that in fact, they were not as American as they thought.

What are the things you miss the most about the U.S. when you are in France? And what do you think you would miss most about France if you were to return to live in the United States?

I’m basically from a southern culture, my younger years triangulated between Florida, Central America and Venezuela, so what I miss about being there is the easy camaraderie, warmth and casual acceptance in relationships. The structure and formality of French relationships is hard for me. I often don’t see it, and when I do, I don’t know what to do with it. But when I’m in the States, I really, really miss French food! I know, it’s a cliché, but it’s just better. Have you eaten American chicken lately?

I know you’re working on your next book, and that it involves an entirely different period of history than the settings of your other two books. Is there anything you want to tell us about what you’re working on now? Or do we have to just wait?

It’s all I want to talk about! I’m diving into historical fiction for the first time and totally enjoying it. The new book is about Foulque Nerra, the count of Anjou, who invented castle-building as an offensive strategy, constructing more than 100 towers across the Loire Valley. He is a fascinating character, pulled between tendencies toward violence and war and a need for love and redemption. He made three pilgrimages to Jerusalem between 1000 and his death in 1040, looking for forgiveness for things he had done. I’m taking the factual framework of what we know about him and painting in salacious details of motive, personality, relationships. In publishing shorthand, it’s kind of Game of Thrones meets Wolf Hall.

More in Interview, Paris books