La Ruche: A City of Artists in the City of Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

It’s rumored that all artists once stayed at La Ruche, the beehive of studios that many of Montparnasse’s painters and sculptors made home.

Prior to 1900, Montparnasse had been more of a place of vaunted literature than art. Poets outnumbered painters. The neighborhood was home to sheep, the occasional traveling fair, scrubby farms and malodorous abattoirs. Poets from the nearby Latin Quarter used the sublime boulders and rubble from the neighborhood’s ancient system of quarries to artistically perch upon to recite their words.

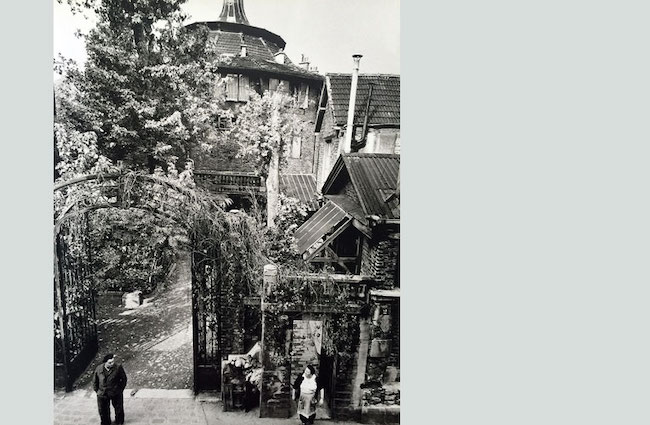

(C) Fondation La Ruche Seydoux

Gradually the sculptors who raided the abandoned quarries’ leftovers began to congregate in the area. These artisans thought the district’s repurposed farm buildings suitable for their work. The spacious greenhouses and warehouses gave them ample room. The skylights and high ceilings were perfect for them.

As Montparnasse became more accepting of the arts, more studios and painting academies cropped up. Near the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, paint and frame sellers set up shop. Models were readily found.

There were communal artists’ buildings, not unlike Picasso’s Bateau Lavoir in Montmartre with a ramshackle collection of rooms with no heat or running water. One was in the Impasse du Maine and the Cité Falgiuère housed Foujita and Modigliani. But the most important was La Ruche.

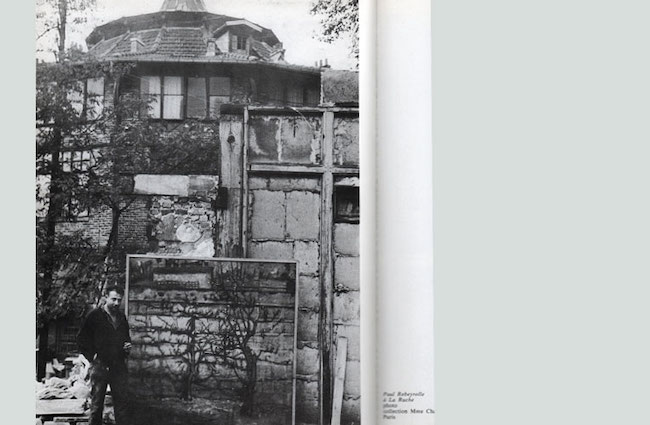

(C) Fondation La Ruche Seydoux

On a whim, the academic sculptor Alfred Boucher bought a cheap plot of land, a wasteland consisting of .4ha downwind from the slaughterhouse region of Vaugirard known as La Zone. Sitting on a bit of a windfall, Boucher was intent on creating a space to help young artists with little resources. Boucher himself was a successful sculptor and had carved the busts of the Queen of Romania and the King of Greece, which paid very well indeed. The creator of a veritable “who’s who” of Paris tombstones, he was also the friend of Auguste Rodin and the one-time mentor of Camille Claudel.

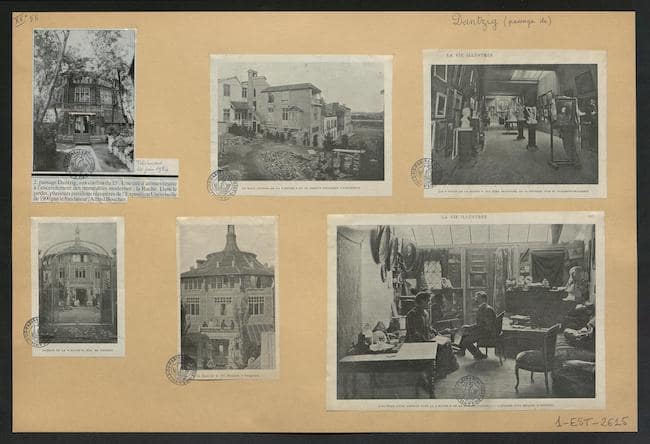

Boucher didn’t build from scratch but created his folly from pieces salvaged from the 1900 Exposition Universelle. He reclaimed most of the Wine Rotunda that Gustave Eiffel had designed as a temporary structure and created over 100 primitive artists’ studios within it. Two caryatids from the British-India Pavilion flanked the front entrance. He sealed it off from the street with repurposed wrought iron gates brought from the Exposition’s Women’s Pavilion. Grandly christened the Villa Medici, the place was quickly known as La Ruche due to its beehive shape and the artists buzzing with intensive creativity within.

La Ruche Montparnasse in 1918. Public domain

Most of the Russian and Eastern European artists who came to Paris around 1910 had no expectations of returning home. The expat Russian community was large and well organized and they made the La Ruche studio complex at 2, passage Dantzig their home. Many artists valid for their time lived there, but their names mean little to us today. However at one time or another La Ruche’s historical occupants included Constantin Brancusi, Marc Chagall, Robert Delaunay, Nina Hamnett, Max Jacob, Moise Kisling, Marie Laurencin, Fernand Léger, Jacques Lipchitz, Marevna, Amedeo Modigliani, Max Pechstein, Diego Rivera, Chaïm Soutine, Marek Szwarc and Ossip Zadkine, plus writers Blaise Cendrars and Guillaume Apollinaire.

An inventor called Gabriel Voisin set on creating a viable aircraft was allowed to stay once he had used up all his savings. His machine was immensely successful. Leon Bakst, famed for making costumes and sets for Les Ballets Russes, also called this place home. Alfred Boucher would have enjoyed the lively and heated discussions emanating from the rooms of his tenants.

La Ruche in 1950. (C) La Ruche Seydoux Foundation

Most of the rooms were tiny triangles with a platform above the door where tenants slept on thin mattresses. The rooms were cramped, squalid, without heat, water, gas or electricity and therefore largely dark. Artist Zadkine described La Ruche as a “sinister Brie cheese, where every artist had a piece – a studio began as a point and ended in a large window.” During sunny days the wide windows, light compared to the thin end of the wedge, were a bonus.

When Boucher bothered to ask for rent, it was just 37 francs per quarter. Alfred Boucher had a laissez faire attitude about rent; he didn’t always insist on it being paid, so La Ruche was usually the first step for artists arriving in Paris. In this way, La Ruche became a home to not just artists, but also an array of misfits, drifters and people down on their luck.

La Ruche in 1950. (C) La Ruche Seydoux Foundation

As early as 1902 small buildings were created around the rotunda of La Ruche that included a 300-seat theater called La Ruche des Arts, exhibition rooms, and an academy where guests could draw from live models. These outbuildings were situated on charming tree-lined gardens and tiny alleyways with poetic names such as Flower Drive, Boulevard of Love, and the Avenue of the Three Musketeers. Some Sundays fairground performers would show up in the gardens with minstrels and accordions to remind the émigré artists of their native lands.

During the First World War, La Ruche was requisitioned for refugees arriving from the Champagne region. The lawns around the rotunda became vegetable gardens. Trees were sacrificed for firewood. Marc Chagall had lived at La Ruche since 1910. He painted many of his famous works there including his “Fiddler on the Roof”. Chagall retreated to Russia during the war and didn’t return until 1923. The building’s concierge let himself into Chagall’s studio and helped himself. The roof of the porter’s rabbit hutch was in need of repair and the concierge replaced it with panels made from Chagall’s abandoned paintings.

Scrapbook of La Ruche. (C) BNF Gallica/ public domain

La Ruche consolidated the artists’ studios dotted around the 13th and 14th arrondissements. After the First World War, it supplanted Montmartre as Paris’s artistic hub.

Boucher, despite his dedication, was no longer in vogue and as money was no longer coming in, La Ruche fell into decline. Boucher died in Aix-les-Bains in 1934. After World War II, La Ruche was a dilapidated wreck. The French Resistance was active in La Ruche and it was a hiding place for weapons.

La Ruche was temporarily reborn as an artistic center when the Salon de la Jeune Peinture was created. However, by the end of the 1960s, when La Ruche was no more than a “slum stuck in muddy ground,” the heirs of Alfred Boucher decided to sell the property to a real estate developer for inevitable demolition. It was then that a defense committee formed. Spearheaded by Marc Chagall, dozens of other personalities including Jean-Paul Sartre, Alexander Calder, Jean Renoir, and Sonia Delaunay came together to save the once-thriving city of artists. However, the auction bringing together paintings and sculptures by resident artists and elders wasn’t enough to buy La Ruche back from the developer.

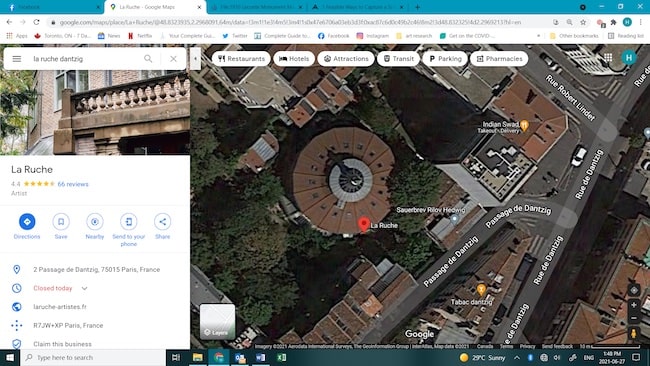

La Ruche via Google Maps

The Seydoux family, philanthropists who were concerned by the imminent disappearance of one of the last artists’ communities in Paris, donated the remainder to save the building. Once the rescue was completed, restoration work was undertaken, thanks to the action of the Ministers of Culture at that time, Jacques Duhamel and Bernard Anthonioz. La Ruche was turned back into a collection of working studios. Since 1972, the facades and roofs of the buildings have been listed as historical monuments. From 1985, the La Ruche-Seydoux foundation has managed the site. The city of artists is still very much alive and artists continue to create new works there.

The restored La Ruche now hosts upward of 50 artists. Some of the artists assembled there have been under the dome of La Ruche for over 50 years. Their rents are still ridiculously small. An article by Benoit Hasse in the June 11th, 2019 edition of Le Parisien ratified the low rent via the words of ceramicist Leonard Léoni. Born in 1933, Léoni is the oldest occupant of La Ruche and the most enduring tenant. “I was born there and have always lived here. My grandfather, an artist too, was one of the first to settle there.” The octogenarian confirmed, “It’s true that we pay almost nothing.” These reasonable rents unfortunately don’t cover the heavy costs of maintaining the buildings of La Ruche. Therefore, the La Ruche-Seydoux foundation regularly calls for donations.

Exhibitions at La Ruche are open to the public all year round. Each exhibitor manages their own opening times. The gardens and the interior of the rotunda can only be visited with the accompaniment of a guide. The exterior alone may be well worth the visit.

La Ruche

2 Passage de Dantzig, 15th

Métro: Convention

Exhibitions listed on the Facebook page

Lead photo credit : La Ruche Seydoux (C) La Ruche Seydoux website

More in artists, exhibition, Montparnasse, painting, Paris, sculptor

REPLY

REPLY