Jacques Villeglé, the Poster Thief of Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The walls of Paris’s buildings have always been a canvas for artists, from early Roman graffiti to today’s taggers and street artists all basically saying “je suis ici,” here I am. It’s no wonder that after World War II, artist Jacques Villeglé found inspiration in Paris’s walls: adorned with colorful paper posters advertising everything from cinema to products to concerts.

Like any good street artist, he waited until the right time to strike. Over time, the layers of posters on a street would be torn and ripped by passersby, also by the team pasting up new posters. At this stage they became, in Villeglé’s perspective, Post-Cubist art, and so he boldly ripped the thick layers from the walls, in effect stealing them. Villeglé took the stolen, rolled up posters to his art gallery then mounted them on canvas. He presented the layered, ripped posters as a new kind of art alongside a group of avant-garde artists called Les Nouveaux Réalistes such as Niki de Saint-Phalle, Yves Klein, Christo and his wife Jeanne-Claude.

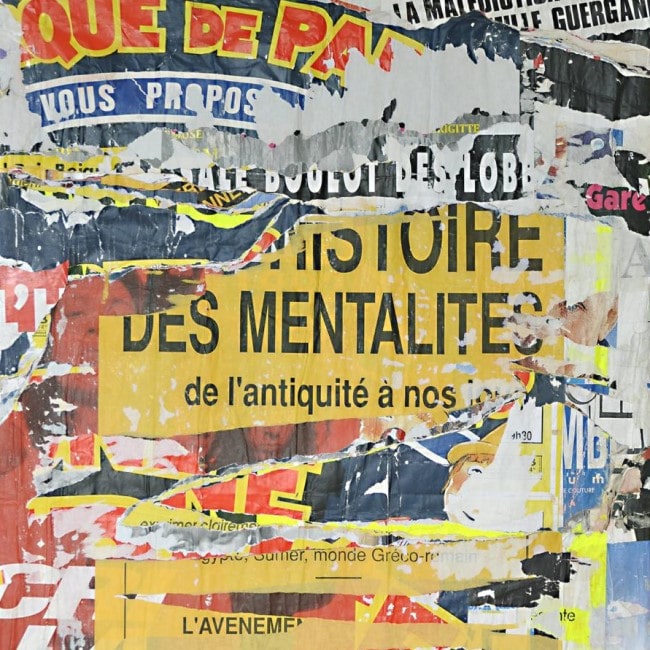

Jacques Villeglé, Rue Pastourelle, 1972, 25 x 27 inches. © Modernism Inc., San Francisco

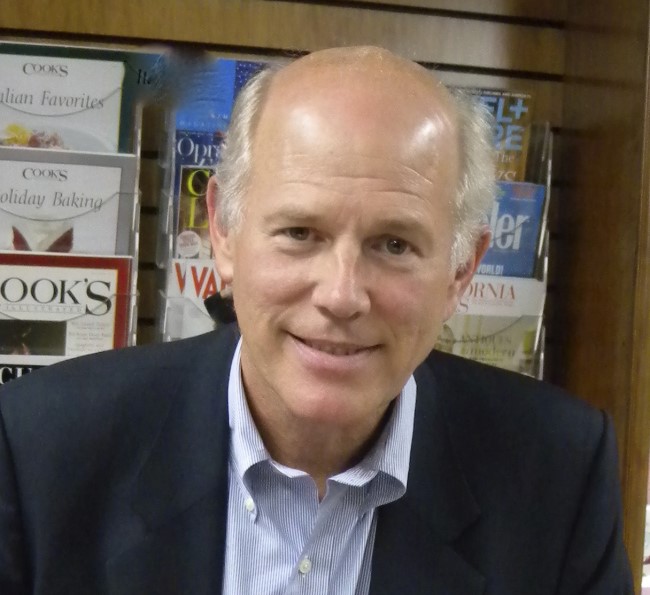

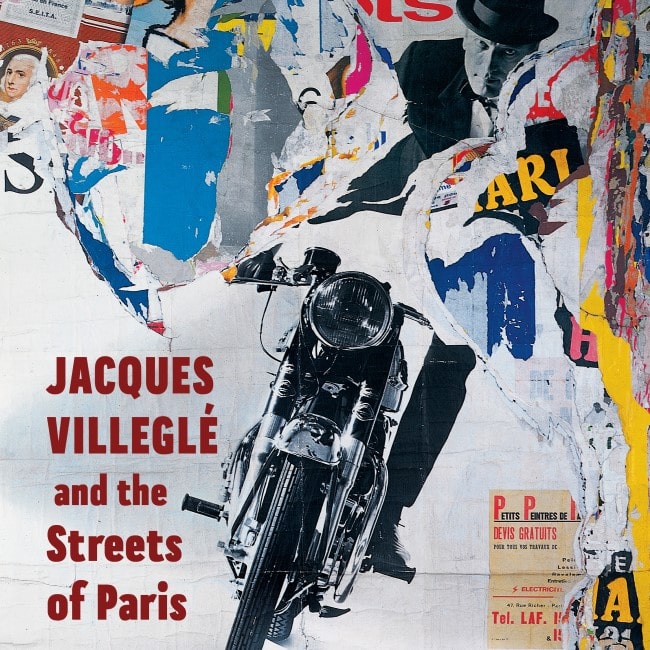

Villeglé’s life story is told in Jacques Villeglé and the Streets of Paris by Barnaby Conrad III. It’s the first English language book on Villeglé who turns 96 on March 27 and lives in Paris and St-Mâlo, Brittany. It’s full of pictures of Villeglé’s art – and a few of him stealing posters on the streets of Paris. Conrad first got to know Villeglé in 2004 in Paris and was inspired to write the book, ultimately interviewing Villeglé over three years’ time. The book covers Villeglé’s entire life but is told in the manner of an ongoing conversation between the two men. They meet throughout Paris in cafés like Brasserie Lipp, walk the streets where Villeglé found and stole his famous posters, or visit Villeglé’s atelier on rue au Maire. It’s like an ongoing tour of Paris listening to these two men chat.

Jacques Villeglé, Sorbonne, January 1992, 44 78 x 35 inches. © Courtesy of Modernism Inc., San Francisco

Conrad is an excellent historian about things French and an artist in his own right. He was born in San Francisco and graduated from Yale with a B.A. in Fine Arts in 1975. In New York he served as senior editor of Art World and Horizon, and editor-at-large at Forbes Life. He was a correspondent in Paris for the San Francisco Chronicle from 1982-87 and has written a number of books including several with French angles such as Absinthe: History in a Bottle (1988), Les Chiens de Paris (1995), and Les Chats de Paris (1996.)

Although trained as an architect, Villeglé and his friend Raymond Hains explored various types of abstract art but Villeglé wasn’t inspired. His inspiration came when the friends were walking on Boulevard du Montparnasse the winter of 1949 and spotted a huge collection of torn posters on a fence. They impulsively stripped them off, took the sections back to their apartment, and created an eight-foot-long mural of tan, red and black shapes and letters they named Ach Alma Manetro. It ultimately became their first masterpiece and was acquired by the Pompidou Center in 1987.

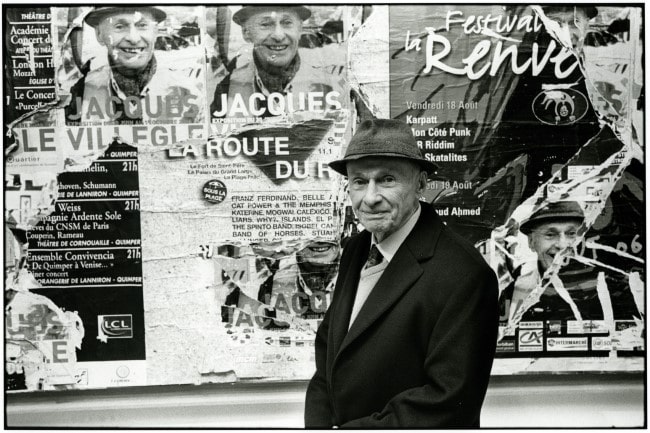

Jacques Villeglé, quai d’Ivry, 27 novembre 1989. Photo by François Poivret

Conrad asked the question, “Were people watching you?” Villeglé’s answer was, “No one cared! They probably thought we were workmen cleaning up the fence.”

Throughout the book there is a discussion between the two men about the philosophy of Villeglé’s art. Other artists created pieces made of torn colored paper and letters so what was the difference between their work made in a studio and Villeglé’s “Lacéré Anonyme” – artwork made by “anonymous lacerators” whose hands ripped up posters that Villeglé would then steal from the streets?

Villeglé portrayed himself as a medium for the faceless people who actually tore and reshaped the posters into something that caught Villeglé’s eye. “What I like above all about the posters is the disorder,” he said.

Villeglé working in the Rue de la Perle, 1962. Photo by J.P. Biot

In another chapter Villeglé said, “Hains and I took something useless … created by multiple human hands – and called it ‘a painting.’ It actually becomes something else. It becomes unique. And then it becomes artwork.” He also said, “…the anonymity gave me the liberty to choose posters where the theme, composition or color could shock me. The posters allowed me to embrace eclecticism – all different styles, from figuration and surrealism to abstraction and Pop.”

In another discussion Villeglé says, “…Our work didn’t come out of Cubist collage as practiced by Braque or Picasso … but out of reality, the street itself.” Ultimately Villeglé claims, “I’m not a philosopher! I’m an artist who steals posters! Picasso and Dubuffet stole a lot of ideas from other artists. Art is theft.”

Author Barnaby Conrad III

Villeglé’s first sale was in 1959 to Swiss collector Hilda Dreiding-Guggenheim. His first solo exhibition was that year in Paris and he spent the next few decades working with Les Nouveaux Réalistes and building his art career. He was one of the few artists that had a strong family life and a full time job as a building inspector for the City of Paris. His job took him out on the streets which allowed him to spot posters at construction sites and see their changes over time.

Villeglé has spent most of his life watching the streets of Paris change. He was born into an aristocratic Brittany family in 1926 and moved to Paris in 1944 after the Liberation. Advertising used posters for many years but technology changed that. Radio, television and computers with apps like social media changed advertising and now there is much less on the streets. Plus, advertising itself became electronic with signs that change every few seconds. The book spends many interesting chapters about his life as he developed as an artist, how the art world discovered and treated him, and how art itself changed with influences from Pop Art and street artists that took over tagging Paris’s walls.

Conrad claims that Villeglé stole more than 4,500 poster works from all 20 of Paris’s arrondissements between 1949 and 2003. At that time, Villeglé retired from his Paris day job and worked to promote and build his collection with art dealers and museums around the world. He became famous in France and Europe and is beginning to be recognized in the U.S. In 2003, an exhibit was held in San Francisco and the San Francisco Chronicle gave a positive review. Art Critic Kenneth Baker wrote, “Representing the conscious intentions of un-numbered hands, Villeglé’s decollages may be beyond critical interpretation. If so, that makes them an underestimated artistic phenomenon.”

But to Conrad, it was Villeglé’s interesting life that helped him develop his art.

“He’s heading toward a century of French life and I think he, like Paris, is always old and new,” said Conrad. “Jacques is kinda old but new as new things interest him. I hope that people remember how wonderfully graphic and visual Paris was with posters that were there because they are all gone now. Jacques saved pieces of history and we may have taken it for granted about how everything changes. He is very much a historian of Paris and I think people will be interested to see how typography was different, varied and rich and to remember something before the world of electronics.”

To enjoy Villeglé’s art in Paris, the Centre Pompidou Musée National d’Art Moderne has several of his pieces including the first piece Ach Alma Manetro. The Galerie Georges-Philippe & Natalie Vallois on Rue de Seine showcases his art. Villeglé can also be found in the collections at London’s Tate Modern and New York’s MoMA and in dozens of museums throughout France and Germany.

The book Jacques Villeglé and the Streets of Paris by Barnaby Conrad III is available for preorder at Inkshares, Amazon and Modernism, Inc. It will be published on May 31, 2022.

Lead photo credit : Jacques Villeglé, 7 avril 2016. Photo by François Poivret

More in Art, history, posters, street art