‘Facing the Sun’ at the Marmottan-Monet Museum

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

“I’m fencing and wrestling with the sun. And what a sun it is…” — Claude Monet, 1888

Following the sun’s path, I ventured east to west to a small museum in a less-visited part of Paris. The late October weather was incredibly warm and prolonging the extent of the sun’s influence seemed vital before a drab, and very possibly cold, winter.

Drawing me to the western edge of Paris is the exhibition “Facing the Sun: The Celestial Body in the Arts,” on exhibit at the Musée Marmottan Monet from 21 September 2022 to 29 January 2023.

Facing the sun, courtesy of Hazel Smith

There’s more than the sun to soak up, so to start, a little history. In 1882, Jules Marmottan acquired the former hunting lodge of the third Duc du Valmy, built circa 1870 on the border of the Bois de Boulogne. Upon Marmottan’s death, his son Paul transformed the mansion into a luxurious townhouse, where he displayed the medieval and Renaissance collections inherited from his father, along with his own objets d’arts. Paul Marmottan, in turn bequeathed the house and all its collections to the Academie des Beaux Arts. A mere two years after his death in 1932, the house reopened as the Musée Marmottan. Since that time, the collections have doubled due to various gifts and bequests.

courtesy of Musée Marmottan Monet

A donation in 1940 by Victorine Donop de Monchy brought Impressionism to the Marmottan with works by Morisot, Renoir, Sisley, and Monet’s Impression Sunrise, the work whose name baptized the Impressionist movement and the raison d’etre behind “Facing the Sun.”

In 1966, Michel Monet, the painter’s last direct heir, bestowed the paintings he had inherited from his father to the Marmottan, making it the largest collection of Monet’s works. It’s known today as the Musée Marmottan Monet.

This bourgeois mansion is abundantly decorated in a lush 19th-century style. Neo-classical figures flank the checkerboard marble floor. Through rooms and corridors painted in a blue spectrum ranging from subtle goose-egg blue, to Wedgwood, to rich teal, are decorative items including a spectacular golden dinner service. Many portraits dating from the Directoire period line the walls, as does a selection of deep-dives, lesser-known gems from the usual cast of Impressionists. Monet’s paintings of Giverny are found on the lower level; Berthe’s Morisot’s Impressionistic works are on the upper level atop a magnificent curved staircase.

courtesy of the Musée Marmottan Monet

The exhibition “Facing the Sun,” found on the museum’s main floor, is housed in a modern, hushed, art-friendly exhibition space. It’s a 21st-century room within a 19th-century one. In this subtly lit inner sanctum, walls painted near-black, others autumn gold, serve to enhance the works of art.

The exhibition is a collaboration between the Musée Marmottan Monet and the Museum Barberini, Potsdam. After work carried out in 2014 by historians and astrophysicists, it was precisely determined that Claude Monet’s Impressionism, Sunrise was painted on November 13, 1872 – almost 150 years to this day. Curators Marianne Mathieu, Scientific Director of the Musée Marmottan Monet, and Dr. Michael Philipp, Chief Curator at the Museum Barberini, joined to celebrate the sesquicentennial of Monet’s famous painting. Their clever exhibition ranges from early Egyptian pieces to art completed as recently as 2019. A selection of 100 artworks from galleries worldwide have been displayed chronologically to reveal the changing representation of the sun in art from antiquity to the present day.

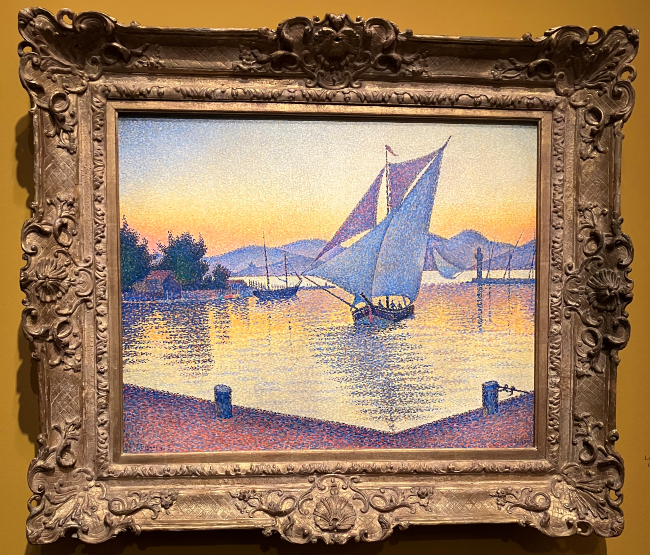

Paul Signac, 1892, Saint Tropez, Opus 236, the Port at Sunset, Museum Barbarini, Germany. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

The curators have gathered some of the greatest masters of art to celebrate art history’s most influential sunrise. Important names are included here, like Albrecht Dürer, Peter Paul Rubens, Claude-Joseph Vernet, William Turner, Gaspar David Friedrich, Gustave Courbet, Eugène Boudin, Camille Pissarro, Paul Signac, André Derain, Félix Vallotton, Edvard Munch, Otto Dix, Joan Miró, and Alexander Calder. Their paintings, drawings, engravings, and 3D works interpret the omnipotent sun.

In antiquity, the sun was precociously perceived as the creator of life, and bygone civilizations took a heliocentric view. They gave the sun a dominant place in their iconography. The Egyptian sun god Ra took pride of place as the father of all creation. However, in the Old Testament, Genesis put paid to the heliocentric ideal, by affirming that the sun and his nocturnal sister the moon were created on the fourth day: “Let there be light.” The Christian god eclipsed the sun in medieval iconography. God commanded the space in artistic compositions, often holding the orb of the sun in the palm of his hand, no larger than an apple.

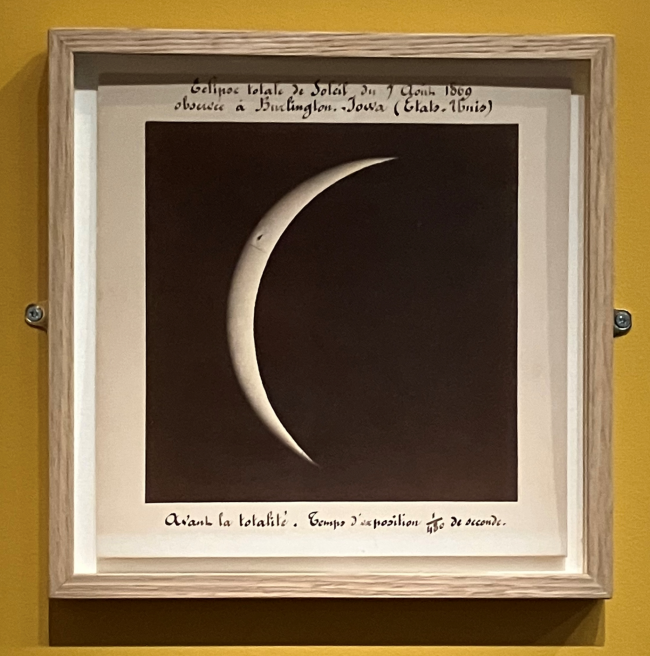

Anonymous, Total Eclipse of the Sun – August 7, 1869, Observed at Ottumwa, Iowa, source Bibliotheque de l’Observatoire de Paris. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

A mid 14th-century Florentine painting, The Vision of St Benedict by Giovanni del Biondo, shows a celestial sun with the holy man shielding his eyes from its overwhelming rays. Benedict sees the vastness of the world encompassed in a single beam of supernatural light. This divine illumination opened his soul to the true size and significance of the world. The gold leaf depicting Benedict’s vision further insists on the monk’s solar vision.

Del Biondo – Vision de Saint Benoit, end of 14th century, AGO Toronto. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

Pride cometh before a fall. Like Icarus who dared to fly too close to heaven, is Phaeton, one of Hendrick Goltzius’ Four Disgracers. The overly muscled Phaeton ignored his father’s urging not to drive the sun god’s chariot and was punished for his hubris.

Hendrick Goltzius, Phaeton, from the Four Disgracers, 1588, The Met. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

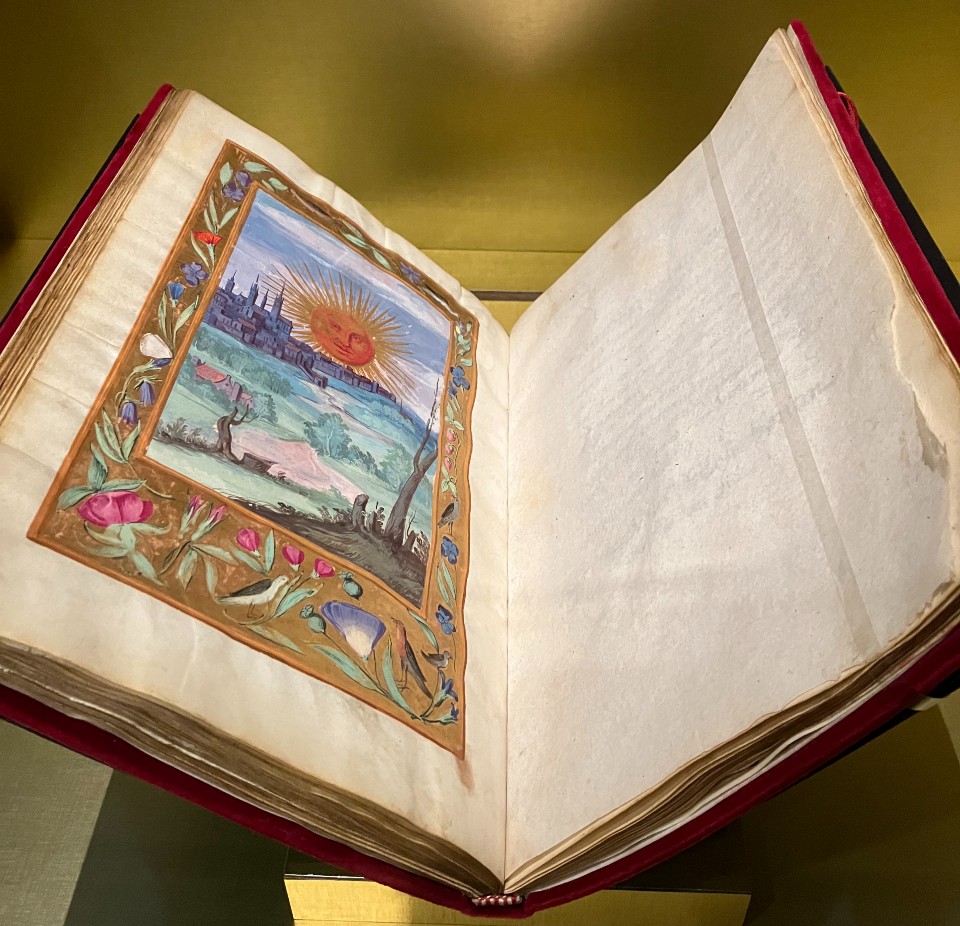

Joachim von Sandrart’s Allegorie du Jour 1643 treats the sun as a trinket. The heliotropic sunflowers behind the subject’s shoulder turn their floral faces to the sun. A gloriously illustrated but anonymous 16th-century work, Coucher de soleil sur la ville, from the volume Splendor Solis Traite d’alchemie, shows a cheeky sun setting on an unknown kingdom.

16th-century work, Coucher de soleil sur la ville from the volume, Splendor Solis Traite d’alchemie. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

The antics of the Sun King, Louis XIV, confirm that the sun of ancient legend had not in fact disappeared. The allegorical sun impressed 17th-century sovereigns, who adopted the sun as their symbol to justify their divine right to rule. Louis XIV freely borrowed details of ancient myth, particularly those relating to the god Apollo. The sun would not only beam down from the ceilings at Versailles but also from Louis’s costumes for the ballet, from his over-the-top headdresses to the buckles of his shoes. Louis also enlisted scholars to study the heavens in the name of science. In 1666, he established the Royal Academy of Sciences, and the Paris Observatory. The “Facing the Sun” exhibit doesn’t just house paintings; there are also maps, manuscripts, gadgets and measuring instruments from the Paris Observatory.

Postcard of Henri de GIssey – Noces de Thetis et Pelee, Apolon 1654. Paris Bibliothèque de Institute de France. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

Chronologically following the path of the sun, we arrive at the much-feted Impression, Sunrise by Claude Monet, which we now know was painted on November 13, 1872. This masterpiece changed the course of art history. Painted en plein air, Monet depicted a misty dawn at the entrance to the port of Le Havre. The orange/red disc, no bigger than a thumbnail is the sun breaking through. His iconic piece went on to lend its name to Impressionism. Art critic Louis Leroy snidely wrote of Impression, Sunrise, “Impression! Of course. There must be an impression somewhere in it. What freedom … what flexibility of style! Wallpaper in its early stages is much more finished than that.” Yet, just a few years later, the reputation of Monet and his fellow Impressionists could hardly have been more different. Not only were their paintings selling to avid collectors, but subsequent exhibitions were visited by thousands of people opening the way to surely the most popular art movement in the world.

Detail from “Impression Sunrise.” Photo credit: Hazel Smith

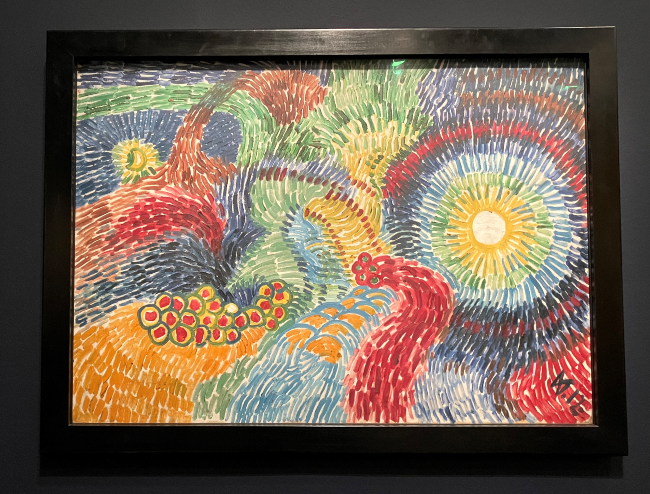

In the 19th century, the sun was no longer a mystical phenomenon, but became understood scientifically as a giant, renewing sphere of flaming gas. Solar eclipses were tracked, photographed and recorded. The science of Spectroscopy used a prism to break down the sun’s pure white light into the rainbow-colored spectrum. Signac, like Seurat, disassembled color and put it back again anew, making a recipe for color that our eyes took in and absorbed. Wilhelm Morgner took the sun and made it dance with unexpected colors. His 1912 Astral Composition evokes Van Gogh’s Starry Night with the energy of a child let loose with felt pens. Sonia Delaunay’s interrupted arcs and rays create colorful sun-like halos.

Wilhem Morgner, Astral Compostion XII 1912, Wilhelm Morgner Haus. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

Edvard Munch’s Le Soleil 1910-13, featured on “Facing the Sun’s” promotional material shows the sun almost as an extraterrestrial being offering part of itself to the slumbering shoreline of violet-grey boulders.

Also included in the exhibit are mobile works by Alexander Calder and Joan Miro. Artfully lit, their shadows create doubles, further iterating the importance of the sun as a central light source.

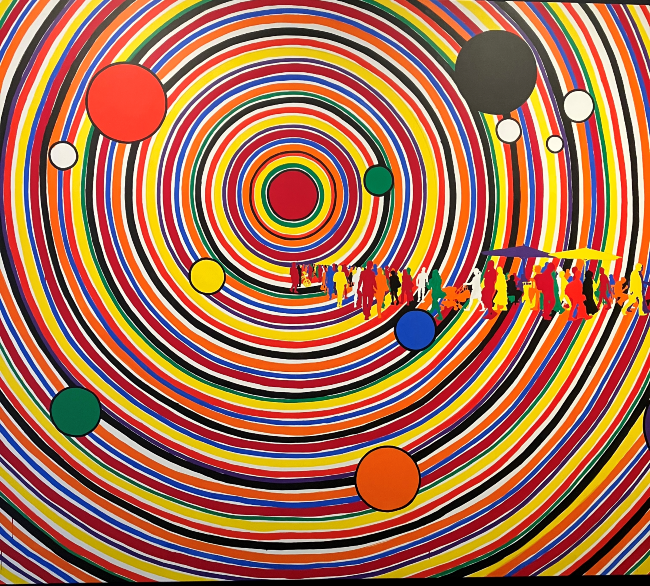

Gerard Fromanger’s Impression Soleil Levant 2019 is a massive painting showing a diminishing line of humanity drawn toward the center of a solar system of concentric rings. Fromanger was asked by the Marmottan to create his own version of Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, and came up with an image reminiscent of long-gone cinematic time machines. To me it was evocative of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Are they seeking sustenance? Will they emerge from their encounter with the sun renewed? Unscathed? Will they come out at all?

Detail of Impression, Soleil Levant 2019 by Gerard Fromanger, Collection Anna Kemp. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

“Facing the Sun” is a cleverly curated exhibition, uncovering for the viewer an esoteric element in art that may not have entered our consciousness. Creating such an exhibition from such disparate sources is quite brilliant. Unfortunately, even with such a lovely building as its home base, the show still looks very much like traveling exhibition, but with lighting and environmental concerns, the room within a room is completely logical.

Is it worth the visit to Paris’s western Périphérique? Yes. Included in the price of admission are a wide array of Monet’s Giverny paintings and a charming look into Berthe Morisot’s life and work.

DETAILS

Musée Marmottan Monet

2, rue Louis Boilly, 16th arrondissement

Tel: + 33 (0)1 44 96 50 33

The nearest metro stations is La Muette or Ranelagh on line 9.

Open Tuesday-Sunday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Closed Mondays. Late closure on Thursday at 9 p.m.

The full-price ticket for “Facing the Sun” is 13,50 €.

Lead photo credit : "Impression, Sunrise," by Claude Monet, 1872, at the Marmottan-Monet Museum. Photo credit: Hazel Smith

More in Art, artist, culture, exhibition, facing the sun, marmottan-monet museum, Monet, musée marmottan monet, Museum, Sun

REPLY