Meet Marie Antoinette’s Favorite Artist

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun really should be much better known. The story of Marie-Antoinette’s favorite artist is a string of triumphs despite all manner of obstacles. She faced deep-rooted misogyny, both personally and in her career, she was a well-known royalist when the Revolution erupted in France and she spent well over a decade in exile, traveling between the royal courts of Europe, paying her way through commissions for her work. She was a single mother, traveling with a young daughter, yet due to a combination of artistic talent and business acumen, she thrived and was highly thought of wherever she went. What a woman!

An artist of repute

Élisabeth drew endlessly from a very early age, encouraged by her painter father who spotted her talent when she was only 8, saying: “If anybody was born to be a painter, my child, it’s you.” Despite her grief at her father’s death when she was only 11 and the arrival in her life of a stepfather who was not kind to her, nothing deterred her from pursuing art. By 1760, when she was only 14, she was visiting the Louvre to learn from and copy the paintings there, and a year later she sold her first portrait, a painting of her mother. Such was the general admiration for her work that at only 21 she got her first royal commission, a request for a portrait of the Count of Provence, the future Louis XVIII.

Elisabeth eventually painted most of the royal family, but the moment which changed her life came in 1778, when, aged only 23, she was commissioned to paint a portrait of Queen Marie-Antoinette. The finished work was much praised and over the next 10 years, Elisabeth painted her some 30 times. The two women were the same age and, despite the vast difference in their status, a friendship began. In her memoirs the artist recalled how nervous she had been for the first sitting: “The imposing air of the Queen frightened me greatly.” She continued: “However, Her Majesty spoke to me so graciously that my fear was soon dissipated.”

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun , Marie-Antoinette à la Rose, 1783, Château de Versailles.

The queen enjoyed the sittings, which often took place in her private apartments. They talked, they sometimes sang together and recalling their friendship later, Elisabeth wrote, “I was so fortunate as to be on very pleasant terms with the Queen.” It was largely thanks to Marie-Antoinette’s influence that Elisabeth was finally admitted to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture despite the protestations of the men who ran it. The artist reciprocated the queen’s kindnesses wherever she could. Her well-known work, Marie Antoinette and her Children was painted in 1787 as part of a campaign to improve Marie-Antoinette’s public image and it portrayed her as the loving mother of the royal children.

Versailles, the Chateau, Queen’s Chamber, ©Kallgan/Wikimedia Commons

A life in exile

By 1789 Elisabeth, now in her early 30s, was a familiar face at court, a popular and successful artist. But then disaster struck. In 1789, when the Revolution erupted, Elisabeth knew that her position as a well-known member of the royal court put her in great danger. On the night of October 6th, she slipped out of Paris with her nine-year old daughter and traveled across the Swiss border into a life of exile which was to last 13 years. She spent long periods in Italy, Vienna and St. Petersburg, mainly at the royal courts, paying her way through commissions and attracting admiration for her talent wherever she went. She was made a member of the Academy of Fine Arts of Saint Petersburg, for example, and attracted similarly prestigious honors in Rome and Florence.

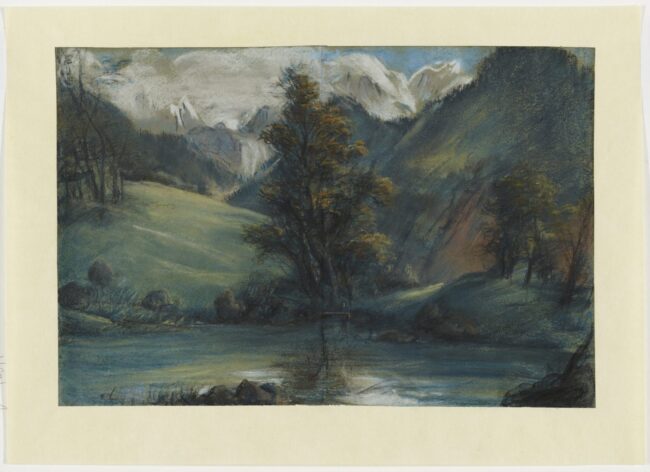

Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, Lake of Challes and Mont Blanc, painted during her travels to Switzerland, Minneapolis institute of Art. Public domain

Meanwhile, she was blacklisted in France and faced imprisonment or even execution if she were to return. Even after Napoleon had seized power, it took a petition signed by 250 artists and politicians before she could return. Out of favor with the Bonaparte regime, she spent a number of years in England and by the time the monarchy was restored in 1815, her rococo style of painting was out of fashion. She never regained the fame she had enjoyed under Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette or abroad, although she did live to see her paintings, which had been confiscated during the Revolution, reinstated in France’s museums and châteaux. She continued to paint into her 80s and died in Paris in 1842 at the age of 86.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, Self-portrait with her Daughter Julie, 1786, Louvre Museum

Three reasons to admire her

There are so many reasons to admire this incredible woman, but the first has to be for her talent and her work ethic. She took every opportunity to learn, from copying works she admired in the Louvre as a young teenager to seeking out the works of famous artists in every city she visited during her exile. Wherever she went she managed to secure commissions and she worked relentlessly. She describes in her memoirs how she did sittings morning, afternoon and evening until it took such a toll on her health that doctors ordered her to rest.

Elisabeth was a trailblazer for women artists. She ignored the fact that female artists were not taken seriously in her day and just devoted herself to painting anyway. When she was 19, the authorities seized her materials, accusing her of being paid for her work without being a member of any guild or academy, despite the fact that acceptance in these institutions was difficult for women. When she was eventually accepted into the Royal Academy of Painting, it was only with the queen’s backing, despite the high quality of her work and the admiration it was attracting. Even more incredibly, she was also a single mother for much of her daughter’s childhood.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Life Study of Lady Hamilton as the Cumaean Sybil, 1792, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Her resilience in the face of her personal circumstances was unwavering. She describes in her memoirs how the money she earned as a young teenager paid for her brother’s schooling after the death of her father. Later, her stepfather expected her to hand over all her earnings to him and she complied for fear that “otherwise my mother might suffer in consequence.” She admitted consenting to marriage “to escape from the torture of living with my stepfather,” only to find that her husband, a painter and art dealer, gambled away much of her earnings and that she had, as she put it, “exchanged present troubles for others.” Incredibly, despite all of this, she completed some 900 paintings in total.

Where to find her today

Many of her works are scattered in galleries across France, Europe and the U.S. Her Self Portrait in a Straw Hat, usually on display in the National Gallery in London, was painted in 1782 when she was in her late 20s and shows her looking confidently straight at us, palette in hand. In Paris, you can find two of her best-known works at Versailles. In the palace itself is Marie-Antoinette and her Children, the poignant depiction of the queen with her three living children, one of whom is pointing at an empty cradle as a reminder of baby Sophie who died in infancy. And in the Petit Trianon, the smaller palace in the grounds of Versailles, hangs a portrait of Marie Antoinette with a Rose, completed in 1783 at the height of her friendship with the queen.

Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, Self-portrait with Her Daughter, 1789. Louvre

In the Louvre you can see a self-portrait of Elisabeth and her daughter Julie, painted in 1789, just before they left France to go into exile. It’s a touching mother-and-daughter image, all the more poignant because they had a troubled relationship when Julie grew up. Elisabeth, saddened but also exasperated by her daughter wrote that “all the charm of my life seemed to have disappeared forever. I could not find the same pleasure in loving my daughter, and yet God knows how much I still love her, despite her faults. Only mothers will understand me when I say this.” Hanging nearby is another picture, Peace bringing back abundance, the picture which finally secured her admittance to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture.

Elisabeth wrote her memoirs in the last decade of her life and they are available in English as The Memoirs of Madame Vigée Le Brun. They give us a glimpse into the mind of this talented, brave, witty woman. Details of her work are mixed with advice on dealing with servants – she sacked one who “did nothing but eat bread and butter all day” – and a warning about robbers, something she recorded “thinking it may be useful as a lesson to absent-minded travelers.” When she recalls a moment in 1814 when the newly returned king waved at her in a crowd as he passed, we are impressed. When she writes of her grief when her daughter pre-deceased her, we are moved: “I saw her again, I still see her, in the days of her childhood. Alas! She was so young. Why did she not survive me?”

Élisabeth_Vigée-Lebrun, Marie Antoinette and her Children, 1787. Palace of Versailles

She also makes a fascinating witness to history, describing momentous occasions and small details in equally lively prose. Recalling a banquet in Saint Petersburg, she describes: “At dessert, on the table were put crystal goblets full of diamonds which were served to the ladies by the spoonful.” Of Napoleon’s return to France from exile in Elba she explains her distress at “the loss of thousands of French soldiers” while Napoleon himself “had never looked so well”. She writes, “Where did his victories lead us? Do we still own any of the land which cost us so dear?”

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun was undoubtedly one of the great portraitists of her day, so it’s unfathomable to report that the first major retrospective of her work was not held until 2015, nearly 200 years after her death. All the more reason then to celebrate her today as a hugely talented artist who succeeded against odds which defeated many other women of her time. In addition to admiring her work, we should be in awe of her commitment, her resilience and her sheer exuberance for life, whatever it threw at her.

Lead photo credit : Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Peace Bringing Back Abundance (La Paix ramenant l'Abondance), 1780

More in Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Louvre, marie antoinette, Napoleon, Versailles