No Appetite

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

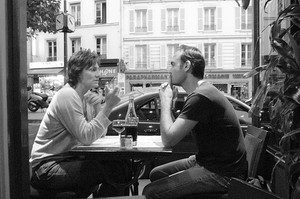

“What’s this? This is a joke? Right? Are these restaurants they’re talking about… what’s the English for trou, foutoir? I don’t understand this.” No, I tell Luc, this is not a joke. Not one of the American restaurants he was reading about in Le Figaro is a hole or a pigsty, and I don’t get it either. Luc is a middle-aged Parisian, has travelled all over Europe, and is improving his English by treating me to dinner. He is contemplating his first trip to the States—“How can one not go when the euro is so strong, n’est-ce pas?” The strength of his currency compared to mine embarrasses him a little, but he’s looking truly upset. The newspaper article was explaining to the French that American restaurants are noisy, to the point of not being able to have a conversation. Luc is horrified—and thinking of changing his ticket.

“What’s this? This is a joke? Right? Are these restaurants they’re talking about… what’s the English for trou, foutoir? I don’t understand this.” No, I tell Luc, this is not a joke. Not one of the American restaurants he was reading about in Le Figaro is a hole or a pigsty, and I don’t get it either. Luc is a middle-aged Parisian, has travelled all over Europe, and is improving his English by treating me to dinner. He is contemplating his first trip to the States—“How can one not go when the euro is so strong, n’est-ce pas?” The strength of his currency compared to mine embarrasses him a little, but he’s looking truly upset. The newspaper article was explaining to the French that American restaurants are noisy, to the point of not being able to have a conversation. Luc is horrified—and thinking of changing his ticket.

It’s not that bad, I tell him. It’s worse. A restaurant reviewer in Washington brings a decibel meter to restaurants and publishes the results next to his ratings of the food, service, and atmosphere. Luc is speechless. He finally gurgles that this last observation is my little joke. No. I tell him I have walked into restaurants widely agreed to have good food and known to have high prices, then have walked out as soon as I encountered a brain-drilling wall of noise at the door. Luc has stopped eating and speaking. For a Parisian to do this in the course of a good meal with a friend suggests something grave has happened—an act of terror or war, a loss to the Germans in the final of the World Cup, an Immortel addressing the other thirty-nine members of L’Académie française in English. Outlandish, unnatural, inouï—leaving one wordless, and for good reason. The critic George Steiner wrote years ago that some things are so horrifying we have no words to express them, only silence. Luc is living proof that silence is language, even eloquence.

He is also a vessel brimming with French expectations, which he would call the facts or simply the truth. A meal, at home or out, is about food, drink, and conversation. If you must eat alone, bring a book and converse with the author or take your chances at the table d’hôte. This is normal. I understand what he’s thinking and agree, but I try to explain further.

This turns out to be a mistake on my part. American restaurants, he needs to understand, are fond of background music—which often seems more like the foreground: to be heard, one must raise one’s voice. Many American restaurants, the more casual ones… What, Luc wants to know, is a “casual restaurant”? Something like a café, I offer, but with hanging plants and a theme—and, let me get back to the point, please. Places like these often have a television going, showing news or sports or whatever the management thinks is appropriate to their particular cuisine. Luc can’t help himself. “How is the television ever à propos to the repast? Voyons, if I am eating the moules and you are having the chicken, can the program be correct for both of us?” He is serious and wants a serious answer. Not to worry, I assure him, many restaurants have more than one TV going—something is sure to please everyone. And besides, the television distracts the diners from the background music, or vice versa, depending.

This turns out to be a mistake on my part. American restaurants, he needs to understand, are fond of background music—which often seems more like the foreground: to be heard, one must raise one’s voice. Many American restaurants, the more casual ones… What, Luc wants to know, is a “casual restaurant”? Something like a café, I offer, but with hanging plants and a theme—and, let me get back to the point, please. Places like these often have a television going, showing news or sports or whatever the management thinks is appropriate to their particular cuisine. Luc can’t help himself. “How is the television ever à propos to the repast? Voyons, if I am eating the moules and you are having the chicken, can the program be correct for both of us?” He is serious and wants a serious answer. Not to worry, I assure him, many restaurants have more than one TV going—something is sure to please everyone. And besides, the television distracts the diners from the background music, or vice versa, depending.

Luc has the cockroach, which is what the French do when they’re glum. He certainly looks as if he has seen one exiting his plate. He asks tentatively if the television drowning out the music is my joke this time, and I promise him it is—a sour one. As he falls silent again, I start thinking of ways to cheer him up. I could remind him of a restaurant not far from where we are right now with belle époque décor that prides itself on its calliope or some similar piece of Victorian claptrap playing loud music from the Gay Nineties, but he knows the place and would answer, correctly, that the music, however bad and loud, is better than the food, so it doesn’t matter, except maybe for tourists and the hard of hearing.

Telling him that Americans habitually talk on cell phones while at table is definitely out—unless I could convince him that talking on a portable is somehow more intimate than talking from lips to ear or that it might actually make it possible to hear one’s companion over, or under, the din, but that would be two cockroaches. I decide not to tell him that a few weeks ago I had a burger in a place with two televisions, even if the sound was off: he would ask if I was looking at the silent screens.

That’s it, that’s the problem. Noise horrifies him the way it horrifies his compatriots, and me, but it’s only one symptom of the more awful social disease, which is distraction. If Luc walked into a room filled with Dürers, Vuillards, Raphaels, or any beautiful pictures, he would no more think of eating a sandwich than peeing on the floor. If you want to admire Rembrandt admiring himself in a self-portrait or watch a football match on television or listen to Vivaldi (all right, Couperin), that’s what you do. These activities, these pleasures, deserve attention, not distraction, and so does dinner. Of course you can talk with a friend about the paintings and the soccer game (discussion of the music has to wait until it’s over), but that is the same as conversation over dinner, without which it is not a meal.

This is not to say that all dinner-table conversations in Paris are scintillating or even interesting. As a semi-professional eavesdropper, I know this, but the dullest conversations still pass for two people saying something to one another. I find myself wondering—and suspect Luc is thinking exactly the same thing—if Americans like noisy restaurants and distractions in general because they do not like to converse: they’d rather multitask, doling out a little stingy attention to half a dozen things at once, no more understanding or caring about what their vis-à-vis is saying than what’s on the TV or the loudspeaker or the computer monitor. If you have to yell to be heard, so much the better: there’s no danger of being subtle, sincere, or even interesting at the top of your lungs—and maybe silence, amid all the din, is golden for those who have nothing to say. Or, Steiner again: “There is something terribly wrong with a culture inebriated by noise and gregariousness.”

Shades of the lonely crowd—or just tactless self-absorption. But what can I tell my friend? He has been looking forward to seeing New York, Washington, and Miami and of course eating while he is visiting. Maybe he thinks he’s going to starve or go McDonalds, equally displeasing. He says something—I am now as distracted as he is and both of us feel rude for letting our thoughts take us away from one another over what’s left of our sad dinner—but I think he’s talking about going instead to Ireland or maybe Iceland.

I want him to see my country. I will think of something. I do not mention the American custom of dinner for two… iPods.

Photo credit: Miles Metcalf/Flickr Creative Commons

Please post your comments and let them flow. Register HERE to do so if you need a user name and password.

More in Bonjour Paris, cultural differences, Dining in Paris, Eating in Paris, English learners, Food Wine, France, French etiquette, French tourism, French wine, Learning English, Paris, Paris bistros, Paris cafes, Paris restaurants, Paris travel