Memorial de la Shoah: Past Exhibit, Benjamin Fondane

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

To live in Paris is to live intimately with its history. Paris has been the stage for many of humanity’s greatest achievements; it has also been the setting for unspeakable tragedy. The Mémorial de la Shoah serves as a reminder of the most horrific of this second category of history, a history difficult to confront: that of France under German occupation during WWII. Through January 31, 2010, the museum dedicates a temporary exhibition to the works and life of Holocaust victim Benjamin Fondane, Romanian poet, essayist, playwright, filmmaker, and philosopher.

To live in Paris is to live intimately with its history. Paris has been the stage for many of humanity’s greatest achievements; it has also been the setting for unspeakable tragedy. The Mémorial de la Shoah serves as a reminder of the most horrific of this second category of history, a history difficult to confront: that of France under German occupation during WWII. Through January 31, 2010, the museum dedicates a temporary exhibition to the works and life of Holocaust victim Benjamin Fondane, Romanian poet, essayist, playwright, filmmaker, and philosopher.

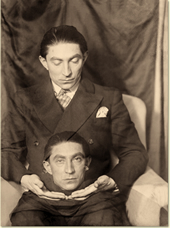

Born Benjamin Wechsler in Romania in 1898, by 1923 he had begun a promising writing career and established himself among the intelligentsia in Paris as Benjamin Fondane. The exhibit includes not only the poetry and essays of Fondane, but works by the artists that ran in his circle as well. These include the striking portrait of Fondane by Man Ray in which Fondane appears to be holding his head in his lap as well as portraits by the likes of Victor Brancusi and Victor Brauner.

Married to Geneviève Tissier (a French woman) in 1931, Fondane became a naturalized French citizen in 1938. After a brief period fighting in the French army, Fondane maintained his residence on rue Rollin during the occupation. It was not until March of 1944 that Fondane was arrested in his home along with his sister, Line, and taken to Drancy, then in May of that same year, to Auschwitz. Although his wife managed to arrange for him to be released on the grounds that he was the husband of an Aryan, he refused to leave the camp without his sister. Shortly after, he was murdered in a gas chamber on the 2nd or 3rd of October, 1944.

The impassioned humanism that emerges in Fondane’s writings is all the more powerful in light of his historical context. His thought was heavily influenced by the Russian intellectual Leon Chestov and more indirectly by philosophers such as Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, and Heidegger. Fondane used his poetry to develop his philosophy, which set a particular store on the individual—a view directly opposite the Nazi rhetoric in which the notion of the individual was only a function of a person’s relationship to the state. Though profound, Fondane nevertheless maintains a simplicity in his language: as he describes in one of his poems, “L’exode” [“Exodus”], of 1942: “Je parle d’homme à homme.” [“I speak of man to man.”]

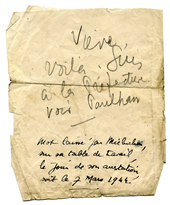

In addition to the numerous philosophical and poetic works on display at the exhibition, the curators have also managed to procure a sizable portion of Fondane’s correspondence. His personal writings reveal the same piercing intelligence as does his academic work—and often an ominous perspicacity. Among these letters, many of them addressed to some of the greatest artists and thinkers of the past century, one small note, in a corner towards the end of the exhibition, persists in my memory. It is only a few lines long, written in pencil on a battered envelope, from Fondane to his wife, “Viève.” It was found on Fondane’s desk on the day he was arrested in his Paris home. The “letter” says close to nothing, if one considers only the words, but brings a stomach-dropping moment to life in a way that defies description. Fondane would never see his wife again. She nevertheless continued to wait for him to come home for one year before learning for certain of his death. In this way, the exhibit is not only of Fondane’s oeuvre, but also profoundly exposes his humanity while calling to mind the humanity of so many others who shared his fate.

In addition to the numerous philosophical and poetic works on display at the exhibition, the curators have also managed to procure a sizable portion of Fondane’s correspondence. His personal writings reveal the same piercing intelligence as does his academic work—and often an ominous perspicacity. Among these letters, many of them addressed to some of the greatest artists and thinkers of the past century, one small note, in a corner towards the end of the exhibition, persists in my memory. It is only a few lines long, written in pencil on a battered envelope, from Fondane to his wife, “Viève.” It was found on Fondane’s desk on the day he was arrested in his Paris home. The “letter” says close to nothing, if one considers only the words, but brings a stomach-dropping moment to life in a way that defies description. Fondane would never see his wife again. She nevertheless continued to wait for him to come home for one year before learning for certain of his death. In this way, the exhibit is not only of Fondane’s oeuvre, but also profoundly exposes his humanity while calling to mind the humanity of so many others who shared his fate.

The decision to focus the exhibit on only one particular man is not only in keeping with the philosophy that Fondane himself espoused, but also reverses the violence of the destruction of individual identity so rampant during the Holocaust, when humans were literally given numbers instead of names. To attend the exhibit is to participate in a kind of resistance as well, that of remembering the individuals a group tried so desperately to erase. Fondane’s writing is more than just philosophically enlightening: it also reveals the human tragedy, the dark history, of the City of Light.

The exhibition will offer several screenings, lectures, and conferences to discuss Fondane’s work as well as the historical context of the period. Additionally, the Memorial will provide free, guided tours for individuals on the 5th and the 19th of November and on the 17th of December. (No reservations are required, and entry to the Memorial is free.)

The exhibition will offer several screenings, lectures, and conferences to discuss Fondane’s work as well as the historical context of the period. Additionally, the Memorial will provide free, guided tours for individuals on the 5th and the 19th of November and on the 17th of December. (No reservations are required, and entry to the Memorial is free.)

The Mémorial de la Shoah is located on 17, rue Geoffroy-L’Asnier. Metro: Saint-Paul or Hôtel-de-Ville. The Memorial is open every day, except Saturdays, from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., and Thursdays until 10 p.m. For more information, visit the Fondaine exposition mini-site or Mémorial de la Shoah.org.