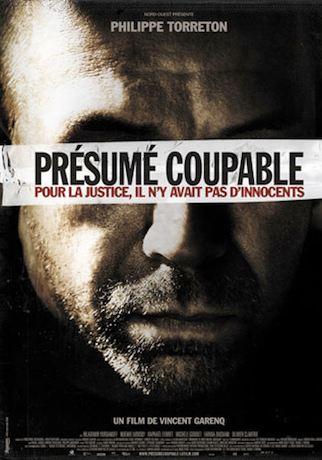

Film Review: Presume Coupable (Presumed Guilty)

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Présumé Coupable: J’Accuse!

Présumé Coupable: J’Accuse!

Presumed Guilty (Présumé Coupable) is a film one can only speak of in strong terms. It is not an uplifting film, but it is the most powerful French film to appear in a very long time. It is a testament of horrific injustice—and ultimate justice, as well, though after seeing this movie the expression “all’s well that ends well” will leave a sour taste in your mouth. Although Presumed Guilty is a semi-documentary feature film, it evokes Shoah more than Schindler’s List. Perhaps the comparison is inapt: Presumed Guilty isn’t about a crime against humanity, but it depicts an innocent man framed for paedophilia and child rape of his own children and others in the small Normandy town of Outreau in 2001. L’affaire d’Outreau rocked French society and has been called the greatest miscarriage of justice in France since WWII. It involved a large group of blameless citizens who were falsely accused; however, director Vincent Garenq chose to focus on the tragedy of a single man, Alain Marécaux.

The role of Marécaux is played by Philippe Torreton, one of France’s greatest actors (former sociétaire of the Comédie Française and winner of the Best Actor César for Bertrand Tavernier’s Capitaine Conan). Marécaux was a huissier de justice, a legal professional with some of the functions of an American process server and marshal. Married, with a brood of children, he seemed to be a paragon of provincial respectability. One night a pack of police raided his house and terrorized his family (here the comparison with the Occupation isn’t so inapt after all). Marécaux found himself roughed up and harshly questioned by police officers. He was strip-searched and thrown into a cell with a group of thuggish cellmates. Afterward, he was interrogated again and again by a bloodless juge d’instruction (investigating judge).

Torreton’s riveting performance is painful to watch, not just because of the horrible things that happen, but because of the impression that we’re seeing the suffering of a real person, not an actor. We remind ourselves that it is an actor we’re watching—then we remind ourselves that he’s playing a real person.

As we follow the ordeal of Marécaux, step by agonizing step, we learn more about the French justice system than we’d like to know. In France, juges d’instruction are in charge of investigating crimes, not district attorneys as in the U.S. The positive side of the system is that the juge d’instruction is neutral, only interested in discovering the truth of a case. Unlike an American district attorney, he isn’t automatically on the side of the prosecution, mostly interested in racking up convictions. The negative side is that, with the status of judge, the juge d’instruction has enormous power. Investigating judges also tend to be quite young; they have been specially trained for their jobs, but they lack the judgment that comes with maturity.

The most Draconian power of the investigating judge is to keep the accused in jail before trial. The concept of bail is not as established in France as in Anglo-Saxon countries. Marécaux wound up staying in jail for about two years. Also, contrary to the American notion of “discovery” (the exchange of relevant information between defense and prosecution), the French principle of secret de l’instruction means that a case can be as opaque as in any dictatorship.

The most Draconian power of the investigating judge is to keep the accused in jail before trial. The concept of bail is not as established in France as in Anglo-Saxon countries. Marécaux wound up staying in jail for about two years. Also, contrary to the American notion of “discovery” (the exchange of relevant information between defense and prosecution), the French principle of secret de l’instruction means that a case can be as opaque as in any dictatorship.

In the past, an additional problem was that the person under investigation did not have ready access to a lawyer. (The accused isn’t officially accused, after all.) This, at least, has been reformed. From nearly the beginning, Marécaux has the assistance of veteran attorney Maître Hubert Delarue. Wladimir Yordanoff gives a solid performance as Delarue, portraying him as competent, intelligent, sympathetic, but limited by the system. He does give a dramatic speech toward the end of the movie worthy of both Zola’s J’Accuse and Lumet’s Twelve Angry Men. But Yordanoff’s character isn’t romanticized—he’s a genuine lawyer, not Perry Mason.

The rest of the cast give impeccable performances. Raphaël Ferret is fine as the smooth investigating judge. Farida Ouchani is thoroughly creepy as Marécaux’s accuser, a low-life child-molester who began making wholesale charges to save herself and her spouse after being caught. Noémie Lvovsky is also fine as Marécaux’s wife, though we get only a dim picture of what she’s going through because the spouses are kept isolated from each other.

The rest of the cast give impeccable performances. Raphaël Ferret is fine as the smooth investigating judge. Farida Ouchani is thoroughly creepy as Marécaux’s accuser, a low-life child-molester who began making wholesale charges to save herself and her spouse after being caught. Noémie Lvovsky is also fine as Marécaux’s wife, though we get only a dim picture of what she’s going through because the spouses are kept isolated from each other.

The film moves implacably forward, with dramatic moments but no real dramas. Vincent Garenq (whose last film was a comedy, Comme Les Autres) shoots the movie in a slightly antiseptic light for the most part, which suggests a documentary. But as the ordeal goes on and on, and as the protagonist’s despair deepens, the movie resembles a contemporary retelling of the Biblical Story of Job. Marécaux takes to praying to God and even to his mother (who dies in the course of his troubles). Whether because of an implicit spiritual dimension or Marécaux’s deteriorating psyche, Garenq’s filming turns a bit distorted—when Marécaux comes out of a cell into bright light, it’s blindingly white. He attempts suicide twice and goes on a hunger strike, and we practically feel his torment. Here Torreton’s performance stands comparison with Robert de Niro in his most demanding roles.

Presumed Guilty is a movie one can describe as harrowing, except that here the word is an understatement. But as you watch, you know that you’re bearing witness.

Official film website & trailer [in French]

Facebook official page

Production Company: Artemis Productions (with France 3 Cinéma, Nord-Ouest Productions, Radio Téléivision Belge Francophone)

Distributor: Mars Distribution (France)

Based on the book by Alain Marécaux, Chronique de mon erreur judiciaire: Une victime de l’affaire d’Outreau

Released in France in September 2011

Photos courtesy: Mars Distribution

Dimitri Keramitas is a Paris-based film writer who reviews the latest French film releases for BonjourParis every other Wednesday. Click on his name to read his past reviews published in BonjourParis.

Subscribe for free so you don’t miss story & don’t forget our searchable library of 6000+ stories about France travel & Paris events, dining, lodging, shopping, French lifestyle news & more.

Get a free copy of Zagat Paris Restaurants 2012/13

Just click and write a few clever remarks about your favorite Paris restaurants …

Who knows?

You might be quoted in the next issue that you’ll receive for free just for participating.

Shop our Amazon.com Boutique for the very latest available at Amazon.com…everything, from books to travelers essentials to music & DVDS, gift cards & imported French good. Merci, your support has allowed us to publish BonjourParis since 1995.

Search hint: start at the back pages for the most recent stock.

Short-cut to our 100 TOP SELLING ITEMS (please wait for widget to load—changes daily)

DVD…Paris: Luminous Years [PBS documentary released Dec 2010]

book…Cannes Cinema [May 2011 release for serious cinephiles; visual history of the world’s greatest film festival.]

book…Fashion in Film [June 2011, collection of scholarly articles that make for stunning look at fashion in film]

book w/movie tie-in…SARAH’S KEY by De Rosnay, Tatiana [Summer 2011 film release in U.S.]

Over 850 past guests rate this hotel 8.7 of 10…an excellent central Right Bank choice

The Joyce Hotel is a 3-star located near several cineplex movie theaters in the heart of Paris. Near Opera Garnier transporation hub, main dept stores & Montmartre. Spacious, chic design rooms (some w/stone walls) were renovated in Summer 2011; hotel opened in 2009. Comfortable rooms w/ free Wi-Fi, AC, soundproofing, iPod dock, organic toiletries & satellite TV. Daily breakfast highly recommended by past guests. Relaxing on-site lounge under the glass roof. Lobby has complimentary light snacks & soft drinks. Great Métro access; near Gare St. Lazare & countless restaurants, cinéma, cultural sites, etc..

859 past guests rate this hotel 8.7 of 10–that’s a lot of happy guests!

**** Eligible for the best-price match guarantee from Booking.com.

Be smart! Reserve your hotel at Booking.com…then keep shopping online & if you find a better rate for the same deal, contact Booking.com for your BEST PRICE MATCH GUARANTEE.

Bookmark this link & use it everytime you shop so your preferences are stored & deals are updated when you return: Booking.com.

More in film review, French film, movie, Paris movie, review