Letters from Paris: Janet Flanner’s Love Affair with the City of Light

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

September 1922: two women disembark from their train at the Gare de l’Est. One is Solita Solano, already an established journalist and critic in the United States. The other is Janet Flanner, still relatively unknown despite some journalistic success in her native Indianapolis. They have just spent two months touring Europe while Solita writes articles for National Geographic. Now arrived in Paris, the City of Light was to remain Janet’s home, off and on, for the next 55 years and become the wellspring of her fame and prestige. Through her “Letters from Paris” in The New Yorker magazine, she carved a unique niche in journalism and nurtured a love of the French capital in the hearts of millions of Americans.

Janet was born in 1892. After expulsion from the University of Chicago for “rebelliousness,” in 1916 she started working as a journalist on her local newspaper the Indianapolis Star and quickly gained a reputation as a theater and early movie critic. In 1918 she married an old university friend called Lane and moved to New York.

She quickly discovered that she and Lane had virtually nothing in common. He was a typical banker while Janet discovered Harlem’s jazz clubs, Greenwich Village’s bohemian scene and the salon of artist Neysa McMein. Fatefully, Janet met Solita Solano at one of Neysa’s parties and fell in love. After an amicable separation from Lane, she traveled to Europe with Solita and thus found herself in a tiny hotel room on the Left Bank.

Solita Solano, born Sarah Wilkinson, was an American writer. Unknown author. Public domain.

1922 was the perfect time to be an American in Paris. Hundreds of ex-soldiers had stayed after the war (especially Black soldiers who found the lack of segregation liberating), bringing jazz and new dances like the Charleston. Other new arrivals also made an impact on the city’s cultural scene. People like Sylvia Beach, who arrived in 1917, opened her famous bookshop Shakespeare & Co. two years later and, in 1922, had just published James Joyce’s untouchable novel Ulysses. Ernest Hemingway was scratching out a living as a journalist and living modestly with his wife Hadley while trying to become a novelist. The Americans brought a kind of showy glamour far removed from the reserved elegance of upper-class French Paris.

Le Select in 2008. Photo credit: Airair / Wikimedia Commons

Janet and Solita threw themselves into this expat scene enthusiastically. Le Select, the Dingo, Bricktop’s – these were the fashionable bars and clubs for meeting other Americans. The pair were regularly seen at the salon of wealthy heiress Natalie Barney and at Shakespeare & Co., meeting and befriending the cream of American literary Paris. Janet felt immediately at home in Paris in a way she had never felt anywhere in America. It was love at first sight, and it never diminished.

She knew she was sexually oriented towards women and regularly cruised the bars known for their lesbian clientele. While people still had to be discreet, same-sex relationships were tolerated much more than in New York. Janet thrived (to the chagrin of Solita who once said Janet still lived with her when she remembered to come home).

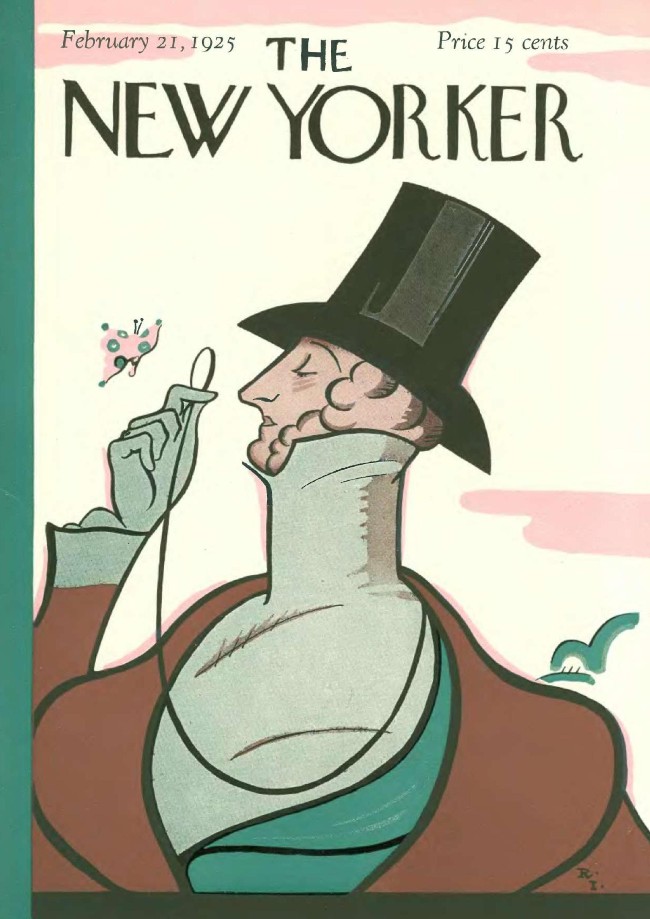

Janet had decided to write a novel, but it proceeded at a snail’s pace. What she had no difficulty doing was writing letters to her friends back in America. These letters were full of Paris gossip, news of gallery openings, theater previews, cabaret shows. One of her regular correspondents was Jane Grant, feminist and wife of Algonquin Round Table regular Harold Ross. When Ross started a new weekly magazine called The New Yorker in 1925, Jane proposed that Janet should write a column in the style of her letters. It would be called “Letter from Paris.” For many years it appeared under the pen name of Genêt (nothing to do with the French writer: Ross thought that was how the French spelled Janet).

The iconic cover of the debut issue of The New Yorker. Public domain.

Although she didn’t know it, Janet had found her vocation. Over the next 50 years she would become synonymous with the magazine and generations of Americans would have their first vicarious experience of Paris through her writing.

For the first few years, the “Letters” continued the witty, gossipy style of her private correspondence. With her pithy one-liners illustrating the movers and shakers of Parisian society, fashionable social events and touching on current affairs, she captured perfectly the essence of the Jazz Age in the City of Light.

As the 1920s ended, however, the atmosphere darkened. Many of her friends lost their savings in the Wall Street Crash and returned to America. Feeling more confident in her writing, Janet started to cover current affairs in greater detail such as the Stavisky financial scandal of 1934. She started writing about events outside France, including the Nuremberg Rallies. In 1935 she persuaded Ross to accept a lengthy profile of Adolf Hitler, who was barely-known in America. Although Janet never actually met Hitler and relied on research and friends in Berlin who had access to his circle, it remains an insightful portrait of the Führer and the new Germany he was creating.

Solita Solano and Djuna Barnes in Paris (Maurice Brange, Au Café, 1922). Public domain

When war in Europe broke out in September 1939, Janet and Solita immediately returned to the United States. It wasn’t exactly Janet’s finest hour to abandon France so quickly, but she admitted she didn’t have the aptitude nor the resources of major news organizations to follow events from the front line. The invasion of France in spring 1940 put paid to any thoughts of returning but she continued to write her “Letters from Paris” from her New York desk. She relied, as she had done with the Hitler article, on her network of correspondents and acquaintances with Parisian connections.

The result was a unique chronicle of life in Occupied France, counterpointing factual newspaper reports with a lively insight into daily life. Readers had a close-up view of the privations, restrictions and downright fear experienced by the French under Nazi rule. One of her best pieces is “The Escape of Mrs Jeffries,” the real-life story of Resistance agent Mary Reynolds as she fled Occupied France to safety back in America. Janet continued her profiles, introducing Americans to the then little-known General de Gaulle commanding his Free French forces from London exile. Her tour-de-force was a four-part profile of Marshal Pétain, the World War I hero turned Nazi collaborator running the Vichy government. It wasn’t just a journalist’s portrait: Janet’s exhaustive research produced a piece of historical analysis in its own right.

Throughout the war years she remained the thread of contact with her readers who longed to visit Paris. By now, her name was synonymous with The New Yorker, whose circulation flourished during the war. When she finally returned to Paris in November 1944, she was fêted by the younger journalists in the American press corps.

Paris, though, was a shadow of its former self. Although it escaped the bombing that devastated cities like London, it was physically and mentally scarred by its four years of occupation. Coal and food were in desperately short supply and it rained incessantly.

Nonetheless, Paris picked itself up and rediscovered its irrepressible joie de vivre on its streets and café terraces. Janet resumed her love affair with the city and her inimitable perspective on Parisian and French life. Her “Letters” discussed the new plays, books (like The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir) and artists that were recreating Paris as a world cultural capital. At the same time, she covered the Nuremberg Trials, Pétain’s trial for treason, and the plight of the millions of refugees trying to return and pick up their lives. Her reputation at home was assured and she was in a unique position to show Americans the realities of life in postwar Europe.

General de Gaulle and his entourage proudly stroll down the Champs Élysées to Notre Dame Cathedral for a Te Deum ceremony following the city’s liberation on 25 August 1944. Unknown author. Public domain.

Although she regularly visited the United States, France was henceforth her home for the next 30 years. Her “Letters from Paris” now read as a fascinating history of France in the mid-20th century. Her eclecticism ranged from the Algerian War of Independence, the funeral cortège of writer Colette, summer heatwaves, the return of de Gaulle and establishment of the Fifth Republic, the student riots of May ’68 and the New Wave of French literature and cinema. Not to mention numerous recollections of France’s cultural icons of the early 20th century as, one by one, they passed away.

It’s particularly illuminating to read her articles on Paris’s redevelopment plans in the 1960s – plans that would have razed its entire historic center for skyscrapers and a grid plan of freeways. And to see how things have turned full circle, so that even the riverside freeway that was built, has been returned to cyclists and pedestrians.

Ill health forced Janet to move back to New York for the last three years of her life. She died in 1978. Throughout her life she had suffered from self-doubt in her abilities. It was only in the 1970s, when she started to win awards, that she finally believed that she had created a body of work that might outlive her. There’s no doubt about that; Janet Flanner is still one of the most perceptive and witty chroniclers of the City of Light.

Janet Flanner, as Uncle Sam, at Nancy Cunard’s fancy dress party, Paris, 1925. Photographed by Berenice Abbott. Public domain

Lead photo credit : Janet Flanner at Les Deux Magots, during the Liberation of Paris, 1944, with Ernest Hemingway. Unknown author. Public domain.

REPLY

REPLY