How the Catacombs Built Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Notre Dame Bridge in 1511, oil by Nicolas Raguenet, 1756

Where did all the ruins go?

Speak about “underground Paris” and visitors usually think of the Catacombs. But few visitors to the city know that these same Catacombs were once quarries used to extract the stone that built Paris throughout the centuries. If the small portion of the Paris Catacombs open to visitors today covers 1.7 km, there are, in all, some 278 km of such halls and passageways beneath the streets of Paris. This is their story.

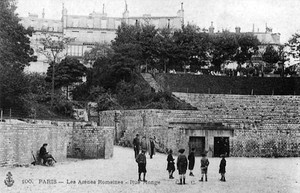

When the Romans invaded Paris in 52 BC and began building temples, baths and a vast Forum they needed a lot of stone overnight. They began by digging open air quarries in the city and replaced the Celts’ adobe wall and branch houses by limestone blocks. Before becoming a showplace for gladiators and other drama, the Lutèce arena in rue Monge was actually the Romans’ first Parisian quarry.

Lutèce arena, 100 AD, Victor Hugo helped save the city’s Coliseum

Over the centuries following the fall of the Roman Empire, architecturally speaking, little changed in Paris. The city became more and “Christianized”, so temples gave way to monasteries and abbeys, but the Merovingian and Carolingian Monarchies during the “dark ages” worked mostly to maintain the bridges, roads, baths, sewers, and arenas, often reusing the stones left from previous Roman structures. Philippe Auguste (1165-1223) used a part of the Cluny baths to build his ramparts.

Clovis was France’s first Christian king and the first monarch to make Paris France’s capital, yet nothing is left of Clovis’ St Etienne church, either. Built in the 6th century and dedicated to Saint Paul, it was totally destroyed when Notre Dame Cathedral was built in the 1100s.

A plaque tells the story of a city built on and from its own ruins

A plaque tells a part of the story: “Here, where we find present day Clovis Street, is where St Peter and Paul’s Basilica once stood. Founded around 510 AD by Clovis, consecrated by St Remi, it was renamed St Geneviève Basilica in the 11th century and rebuilt between 1176 and 1191, by Etienne de Tournay, Abby of St Geneviève. Abandoned in 1790 and destroyed in 1807, only the tower remains, now enclosed by the buildings that house the Henri IV high school, itself built where the former abbey once stood. In 1767 the building of another monument was begun, now known as the Pantheon and originally intended to replace the former Basilica.”

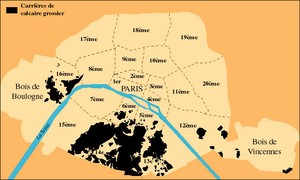

A map of the quarries used to build Paris until the 19th century

Digging deeper into history

Beginning in the 12th century, with the advent of Philippe Auguste (1165 – 1223), more and more people poured into Paris. To avoid wasting precious farm land, the above ground quarries used to extract limestone gave way to deeper and deeper excavation. Philippe built his ramparts between 1190 and 1225 to protect Paris while he was off on the 2nd crusade to the Holy Land with Richard I of England. By clicking on the three photos here, you can see a map tracing the wall and its only remains still visible on both banks of the Seine today. Under Philippe Auguste there were 50,000 inhabitants in the city. By 1328 there were an estimated 200,000 people living in Paris. Their houses lined the city’s bridges and covered the esplanade in front of Notre Dame Cathedral, still under construction at that time. You can see an amazing slideshow of Philippe’s Paris here.

“Colombage” houses in the city of Rennes, Brittany

Most of the houses at that time were built in timber and adobe. Unlike London in 1666, by some miracle, no fires ever swept over Paris.

Whenever former temples or churches were torn down, their stone was used to help rebuild newer religious structures. When more stone was needed, with a few rare exceptions such as Notre Dame Cathedral where rock would be dug up at the foot of the construction or under today 16th and 17th arrondissements to the west, the majority of the city’s structures, as shown on the map below, would all be built with stone extracted from quarries located mainly on the left bank, in or around the Catacombs. One advantage of going underground was also that the stone was much more resistant.

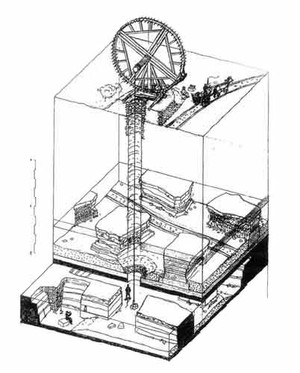

Extracting stone, by use of a squirrel wheel, during the Middle Age

Going to Hell

Traditionally the city of Paris belonged to the King of France and each king leased out the right for individuals to dig tunnels and mine stone. But all that changed in 1601. Henri IV did away with a royal tax paid to contractors hired to oversee such activities. Little by little over the next two centuries, anarchy set in. Tunnels and quarries were formed then promptly abandoned. As a result, streets above began caving in without warning, causing several deaths.

Finally, in 1777, an “Inspection Générale des Carrières” was created in an attempt to solve the problem by consolidating the underground walls and ceilings. On the very day of the Inspection’s creation, the rue d’Enfer, the “street of Hell”, above today’s Catacombs, collapsed and simply “disappeared” swallowing up an entire house!

The Catacombs, once an underground quarry

At about this same time, the stench and insanitary conditions of cemeteries in Paris were also finally drawing public attention. Back in Roman times, Lutitia, the Roman name for Paris, had a population of no more than 50,000 to 80,000 inhabitants. Districts, like Montparnasse, were not as yet incorporated, so Roman cemeteries were still located on the outskirts of the city. But as the population had grown, so had Paris. By the 1500s the city had spread to include both quarries and cemeteries. In 1786, three years before the Revolution, Louis XIV decided to have the remains from most of the Paris cemeteries moved to catacombs.

Stone remains of the Bastille prison in Henri Galli Square, 4th arrondissement

Napoleon slept here

Despite efforts of monarchs like Charles V or Marie de Medici to improve Paris, for the common of mortals, by the 1800s the rest of the city hadn’t really changed much physically since the Middle Ages. With the arrival of Napoleon III and his decision to modernize the capital, the Baron Haussmann altered most of those dark and narrow passage ways into the large avenues and boulevards we see today. In addition to installing a modern underground sewer system, some 20,000 substandard buildings were torn down and another 30,000 new ones built in their place. But, by now, using the left bank quarries was out of the question! Haussmann had to dig up and bring in his stone from the Oise suburbs north of Paris.

In 1913 a governmental decree brought a firm and final end to all mining inside the city of Paris. What remains today, not including either the sewers or the Paris subway, are those 278 km of gallery and tunnel. Over 40% of Paris is built above former quarries, what the Parisians call humorously their “gruyere” or swiss cheese.

Historical sources:

Population in the Middle Ages

History of the Paris Catacombs

Paris in the Dark Ages

Catacombe quarries

History of the quarries in Paris

History of quarries in Paris!

Buildings in ancient Paris

Photos credits:

Oil by Nicolas-Jean-Baptiste Raguenet, Musée Carnavalet, Wikipedia commons

Lutèce arena

Plaque indicating Clovis’ former Basilica

Map of the quarries

Timber and adobe houses in Rennes

Drawing of extraction of stone in the Middle Ages

Quarry worker(Paris Mayor’s site)

Remains of the Bastille

More in catacombs, Paris, Paris history