Suzanne Lenglen: The Tennis Champion Called ‘La Divine’

As a child, I wore my headband flat against my fringe. My dad told me I looked like “Suzanne Long-Long.” My English father’s pronunciation befuddled my little ears. Her name was, of course, Suzanne Lenglen, an athlete whose career had ended even before my father was born. By the end of the 1920s, Suzanne Lenglen was the most famous (or infamous) athlete, newsmaker or celebrity in Europe. She shone as the greatest tennis player in the world.

A century later, the French Open of tennis runs this year from May 22 to June 11, 2023 at the Stade Roland-Garros on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne. The French Open along with the Australian Open, the Wimbledon Championships and the US Open, comprises the annual Grand Slam of Tennis. Played on the best clay court in the world, the French Open is regarded as the most physically challenging of the four.

First held in 1891, the French National Championships were a men’s competition played at the Stade Français, in the Paris suburb of Saint-Cloud. Six years later, women’s matches were added to the tournament. In the days of classic tennis, players competed for silver trophies, not prize purses worth millions. But there was always intrigue and a cast of newsworthy characters. One of which, Suzanne Lenglen, was dubbed La Divine of French tennis. She had a winning percentage of 98%. She won tournament after tournament, losing only one game in seven years.

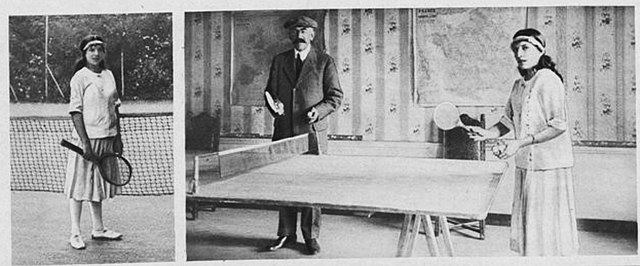

French tennis player Suzanne Lenglen at the French Championships, Photo Credit: Agence de presse Meurisse/ Wikimedia Commons

Born in the 16th arrondissement of Paris in 1899 in the private hamlet of Boulainvilliers, Lenglen triumphed over a rather sickly childhood – she suffered from asthma and insomnia – and went on to excel at a variety of sports. She earned her chops playing a string and spool game of dexterity called Diabolo on the front in Nice, the crowds boosting her confidence.

To boost her strength, her father Charles, known to all as Papa, presented Suzanne with her first tennis racquet when she was just 11. Recognizing her precocious talent, Papa Charles improvised a rigorous daily routine for his daughter which included skipping, sprinting, swimming, gymnastics and dance. Her precise footwork was practiced on a tennis court marked like a checkerboard. Charles dotted the court with handkerchiefs to use as targets. When Suzanne proved her aim, the hankies were folded ever smaller until they were replaced with coins. Though just a girl when she came into the limelight, Charles taught her to play like a man, but she surpassed her male counterparts with her agility and accuracy.

Suzanne Lenglen (left: with a tennis racket; right: with her father at a ping pong table. Credit: Jean Laporte in 1 July 1914 edition of Femina / Wikimedia Commons

At 15, Lenglen was the youngest champion in history when she won her debut game at the 1914 French Championships. At the age of 20, she made a smash at Wimbledon. In less than a decade from receiving her first racquet, she won the women’s championship at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics.

Before the French Championship was open to all comers, Lenglen held the most singles titles in the French Championships, winning the women’s side during the years 1920–1923, 1925–1926. Overall, she won 241 titles during her much-too-short-12-year career. For comparison, Serena Williams, considered the greatest tennis player of all time, has won 73 singles and 23 doubles titles over a career spanning 20 years.

In a day when – to quote a phrase – “women didn’t perspire, they merely glowed,” Lenglen played with power and aggression. Tennis was an appropriately feminine and bourgeois sport and female players deported themselves gracefully. Lenglen had no desire to compete in a lady-like manner. When asked about her method of play she said, “I try to hit the ball with all my force and send it where my opponent is not.” Like a 21st-century player, she wasn’t beyond tossing her racquet when she missed shots. But for Lenglen, missing a shot was very rare.

Suzanne Langlen (1899-1938) (right) shaking hands with Mary Browne (1891-1971) (left). Wikimedia Commons

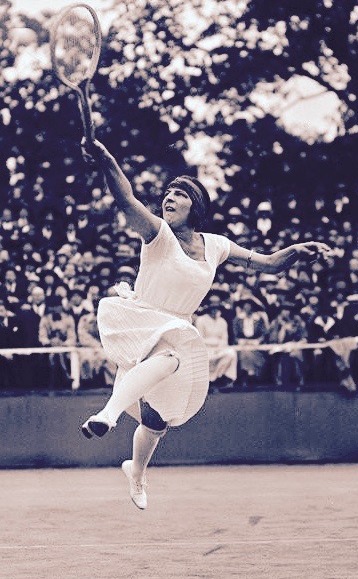

The original tennis diva, Lenglen turned her matches into performances. She played with flair, leaping theatrically around the court. Lenglen was famous equally for her fashions on the court. While most female players were constricted in corsets and ankle-length skirts, Lenglen’s athletic wardrobe consisted of shockingly short knee-length skirts and sleeveless blouses. She was instantly recognizable by her headband, dubbed the “Lenglen bandeau,” a scarf tied around her flapper hairdo and fastened with a jeweled brooch – this is what my father was hinting at. Rubber-soled “Lenglen shoes” of white doeskin, and the much-copied headband, soon trickled into the wardrobes of French women. The French design house Patou provided Lenglen’s La Mode Sportive outfits. Although not a beautiful woman, Lenglen nonetheless became a fashion icon,

The French newspapers raved that her exuberant playing style belonged in the dance world, which resulted in Lenglen’s refusal of the Moulin Rouge’s robust offer to appear in a tableau vivant with her racquet and balls. The French media were always among her biggest supporters. British reporters called Lenglen the “Queen of the Court”, and in truth, she was a bit of a princess, irritable, arrogant and prone to unpredictable mood swings. As a child, she often feigned sickness as her way of taking a much-needed respite and she carried this trick forward into her adulthood. She began to default her matches, citing illness or injury when she was plainly seen drinking or dancing in the evening hours.

Lenglen Cannes 1921. Photo Credit: Agence Rol / Wikimedia Commons

As a young girl, Suzanne’s nerves were calmed by sneaking courtside sips of brandy. It picked up her game, her father noted. When tennis officials took umbrage, her father would toss Suzanne soaked sugar cubes in cognac. It was perhaps not a wise idea to have his young daughter so dependent on hits of alcohol.

Her reputation for tippling preceded her to the 1921 US Open. When it was explained to her that Prohibition forbade her from drinking before matches, Lenglen threatened to return to France. She declared, “Nothing is so fine as wine for the nerves, for strength, for the morale. A little wine tones up the system just right.” Tournament officials kept her plied with contraband booze, her mid-match sips serving to heighten her outrageous reputation. Despite her increasing imprudent lifestyle, Lenglen continued to win match after match gathering numerous titles under her belt in a 179 game winning streak.

Photo Credit: Bain News Service

In February 1926, Lenglen would play what was then called the “Match of the Century,” facing the American Helen Wills at the Carlton Tennis Club in Cannes. The breezy, uncomplicated Wills was a complete contrast to the French star. The match drew worldwide attention. Kings, princes, dukes and a maharaja were in the stands. Fans swarmed over any available seat, some perched in trees, on ladders or on the roofs of surrounding buildings. Lenglen won against Wills but the match shook her confidence and tested her physical limits. It was Lenglen’s last match before turning pro.

Turning professional was a mistake for Lenglen. She was one of the first female players to leave amateur tennis behind. At 27 she announced, “I have worked as hard at my career as any man or woman has worked at any career. And in my whole lifetime I have not earned $5,000 – and not one cent of that by my specialty, my life study – tennis.” Unfortunately, going pro backfired for Lenglen. As a professional, Lenglen could no longer enter certain championships, like the amateur-only Wimbledon. On tour with a handful of less talented women, the outcome of matches was always predictable. Interest dwindled and Lenglen’s playing career ended. She decided to retire from tennis.

French tennis player Suzanne Lenglen playing against Mme Golding at the 1922 French Championships at the Croix-Catalan in Paris. Credit: Agence Rol / Public domain

As an amateur, Lenglen had authored several how-to-books for girls and one work of romantic fiction; The Love Game: Being the Life Story of Marcelle Penrose published in 1925. She continued writing after her retirement, her final book Tennis by Simple Exercises was published in 1937. She worked for a fashion house where she designed women’s knee-length shorts. She coached tennis in Paris, serving as the director of tennis schools for both children and adults. In 1935, Lenglen played the tennis star Madame Bombadier in a British comedy Things are Looking Up. However, Suzanne remained a confirmed mademoiselle despite her five-year relationship with a married man with the impossible name of Baldwin Baldwin.

French tennis player Suzanne Lenglen at her tennis school in 1936., Photo Credit: Agence de presse Meurisse

Though freed from the pressures of the game, health issues still plagued Lenglen. Following an appendectomy, she was rumoured to have leukemia or hepatitis. In June of 1938, she was diagnosed with pernicious anemia. Anemia plus Lenglen’s alcohol intake may have taken a toll on her liver. She died two weeks following an emergency blood transfusion. Alcoholic liver failure is one of the potential causes of Lenglen’s death, as there’s ample evidence of Lenglen’s proclivity for drink. It was part of her myth.

The myth of Suzanne Lenglen once loomed large. She was one of the best-known athletes of the 20th century. Her rise to stardom as a tennis “phenom” was meteoric. However, like many adolescent stars, the constant adulation and the glare of the limelight took its toll. Lenglen’s own light faded too quickly. Today Paris boasts tennis courts, clubs and a metro station named for this striking woman.

Lead photo credit : Photo Credit: Bain News Service

More in roland garros, suzanne lenglen, tennis

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY