The First Colors of Paris: When Photography Got Vivid

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

From neolithic cave painters to the mid-19th century invention of the camera, stopping time and capturing images has fascinated humanity. We are hardwired to express ourselves. The human brain processes images 60,000 times faster than words, and the language of photography has allowed humankind to pictorially record our history.

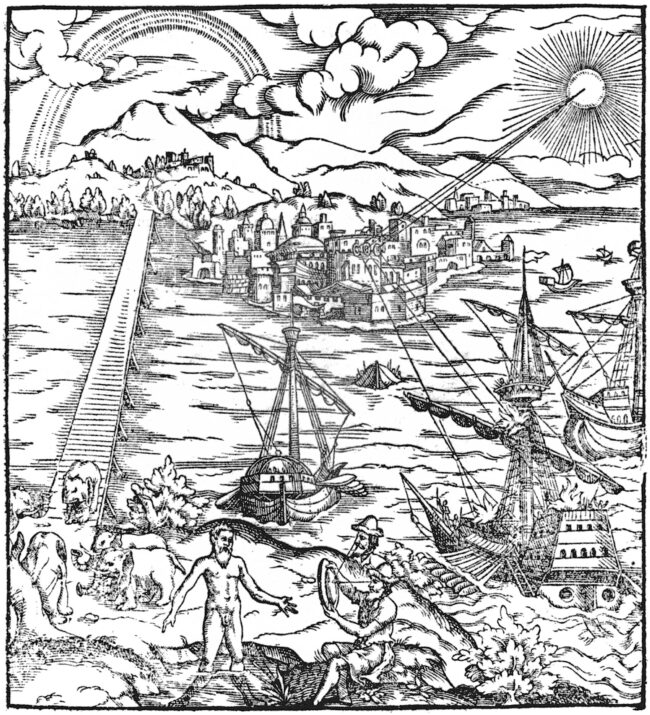

While there was no defining moment that photography was invented, the basic idea existed for centuries and developed over the ages as technology progressed. The earliest cameras such as the camera obscura weren’t used so much to take pictures as they were to study optics. They demonstrated how light can be used to project an image onto a flat surface. The Arab philosopher Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham (965-1040), a mathematician, astronomer, and physicist, is considered the father of modern optics. He studied reflection, refraction and the nature of images formed by light rays. But the actual chemistry needed to record an image was not available until the 19th century.

“Front page of the Opticae Thesaurus, which included the first printed Latin translation of Alhazen’s Book of Optics. The illustration incorporates many examples of optical phenomena including perspective effects, the rainbow, mirrors, and refraction.” Public domain, via Wikimedia commons

The earliest photograph was created by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (French, 1765–1833), produced with the aid of a camera obscura. It was a real breakthrough, after years of developments. Niépce photographic experimented with photography in order to record everyday life. As early as 1816 he produced images, or points de vue, while using a mixture of chemicals, materials, and techniques, creating héliographie, or sun writing. He dissolved light-sensitive bitumen in lavender oil and applied it on a silver plate, then inserted the plate beneath his camera obscura and positioned it near a workroom window. Exposure to sunlight would create an impression on the plate of the courtyard, outbuildings, and trees outside. Ten years later, in 1826, Niépce produced the first “photograph”, View From the Window at Le Gras, the oldest one known in the world today.

Point de vue du Gras, the oldest conserved photograph. Credit: Nicéphore Niépce in 1827. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1829 Niépce established a commercial relationship with the French artist and inventor Louis Daguerre (1787–1851), who owned the renowned Diorama in Paris. He and Niépce both sought ways of using chemistry and light to fix permanent images, but while Niepce’s process remained inefficient due to the slowness and complexity of the various operations, Daguerre produced the first sophisticated photographic process, the daguerreotype, and a more efficient camera. Daguerreotypes are created by covering a copper plate with silver, sensitizing it with iodine, then exposing it to hot mercury. Even though his photographs captured the forms of nature with beautifully rendered detail, and were wildly successful worldwide, they still failed to capture and retain their color.

L’atelier de l’artiste, daguerréotype, 1837. Louis Daguerre. Public domain.

Photography’s potential as a means of documenting reality continued. Attempting to meet consumer demand for realistic images, photographers began to add color to images by hand, but hand-coloring paled by comparison. A practical method of color photography remained elusive until 1868 when Louis Arthur Ducos du Hauron (1837 -1920), an amateur physicist and artist, patented a three-color, trichrome process by combining colored pigments instead of light. Three negatives, taken through red, green and blue filters, were used to make three separately dyed images which when superimposed, produced a colored photograph. In theory, his technique still forms the basis of today’s color processes, but it was not until the end of the 19th century that the first so-called panchromatic plates, sensitive to all colors, were produced.

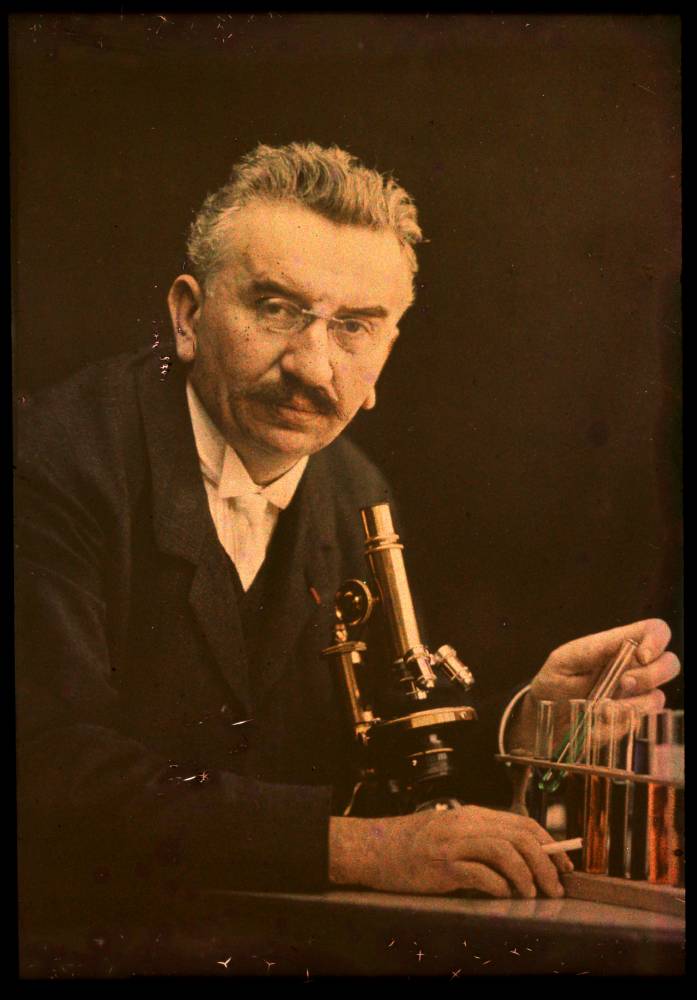

Louis Lumiere with microscope and test tubes, looking towards camera. Autochrome portrait. Circa 1910. Public domain

Based upon one of du Haroun’s ideas, Auguste and Louis Lumière invented the autochrome process. The Lumière brothers grew up in Lyon. Their father, Antoine, a painter, photographer and businessman manufactured photographic plates. In 1881, 17-year-old Louis invented a new dry plate (instant photo process) called etiquette bleue which brought fame and financial success to the family business. By 1894, the Lumières were producing some 15 million plates a year. They were known for their invention of the film camera, the cinématographe (1895), but they also worked on color photographic processes which were exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900. Three years later they patented their invention—Autochrome Lumière.

Auguste Lumière, c. 1935. Henri Lumière. Wikimedia commons

Instead of taking three separate photographs through color filters, the Lumière brothers took one. Autochrome plates were covered in microscopic red, green and blue colored potato starch grains, which were then mixed together and spread over a glass plate coated with a sticky varnish. Carbon black powder was spread over the plate to fill in any gaps between the colored grains. A pressure of five tons per square centimeter was exerted by a roller to spread the grains and flatten them out. The plate was then coated with a panchromatic photographic emulsion. When the photograph was taken, light only passed through the colored starch grains, combining to recreate a full color image of the original subject. These photos were, in fact, halfway between photography and Impressionist painting. Words can’t adequately convey their luminous beauty.

Auguste & Léon Lumière, Autochrome photo, Still Life with Flowers and Oranges, 1907. Public domain

The first public demonstration of their process took place on June 10, 1907 at the offices of the newspaper, L’Illustration, in Paris. Some 600 people, including scientists, artists and politicians, were in attendance. They witnessed, in the words of a journalist from Le Figaro, a “real revolution.” It was a resounding success.

Autochrome Lumière photographs didn’t require a special apparatus so photographers could use their existing cameras. Although complicated and expensive to make, autochrome plates were simple to use, a fact that greatly enhanced their appeal to amateur photographers. They did not require any special apparatus except a tripod, so photographers could use their existing cameras. For a simple viewing, autochromes could simply be held up to the light. For viewing by several people they could be seen by using a diascope, a device used to display transparencies. But when viewed in stereoscopes the images were nothing short of transcendent.

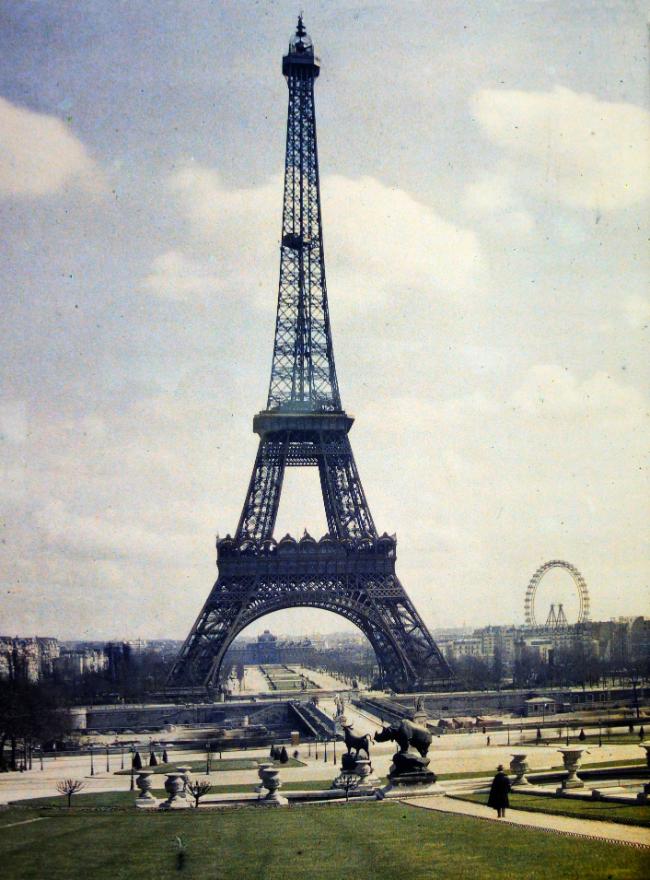

The first color images of Paris transport us as in a dream. These visually stunning clichés are framed in an almost spectral fog, a romantically poetic aesthetic which still defines our impressions of Paris to this day.

Eiffel Tower in Paris photographed in 1914 using the Autochrome process. Photo Credit: Auguste Léon, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Photographic News noted in 1908, “…when the effect of relief is joined to a life-like presentation in color the effect is quite startling in its reality. It is not easy to imagine what the effect of anything of this kind would have been on our ancestors and witchcraft would have been but a feeble, almost complimentary term, for anything so realistic and startling.” The Salon Exhibition of 1908, for example, contained almost 100 autochromes by leading figures such as the American photographers, Edward Steichen, and Alfred Steiglitz, and the French photographers, Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Léon Gimpel, Jules-Gervais Courtellement, and Auguste Léon.

Katherine Stieglitz, c. 1910. Attributed to Alfred Stieglitz. Public domain

By 1913, the Lumière factory was making 6,000 autochrome plates a day, in a range of different sizes. It brought a whole new dimension to the pursuit of realism. The value of the process for scientific, medical, and documentary photography was recognized almost immediately. Created just a few months after the start of World War I, the Army Photographic Section, which centralized and ensured the dissemination of images of the conflict, sent specially-commissioned autochrome experts to the front. Often taken far from the front lines, their images show the consequences of war: destruction, injuries, and death.

French soldier in observation, 1917. An autochrome from the First World War, Photo Credit: Paul Castelnau, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Autochrome colour picture by Jean-Baptiste Tournassoud of North-African soldiers, Pas-de-Calais,1915, Photo Credit: Jean-Baptiste Tournassoud, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1932, responding to a growing trend away from the use of glass plates towards film, the Lumières introduced a version of their own process which used sheet film as the emulsion support, marketed under the name Filmcolor. Within a couple of years this had virtually replaced glass autochrome plates. However, these changes occurred at precisely the same time that other manufacturers were successfully developing new multi-layer color film which reproduced color film doing away with the need for filter screens. It was with these pioneering, multi-layer films such as Kodachrome that the future of color photography lay. The Lumière company was a major producer of photographic products in Europe, but the brand name Lumière disappeared from the marketplace following the merger with the British company, Ilford.

The autochrome was confined to history, but it retains its place among the most beautiful photographic process ever invented. Louis died on June 6, 1948 and Auguste on April 10, 1954. They are buried in the family tomb in the New Guillotière Cemetery in Lyon.

More details An Autochrome of the pavilion of Poland in Paris, 1925. Auguste Léon (1857-1942) – Musée Albert-Kahn. Public domain

In 1854 the Société Française de Photographie was founded in Paris. Starting in the early 20th century, the SFP outlined a mission to protect historic works, and today it also functions as a research center for the history of photography. The association has a valuable historic collection consisting of some 10,000 images and 50,000 negatives including 5,000 autochromes. And thanks to the thousands of photos taken by photographers using the autochrome process, the colors of the first third of the 20th century have been preserved by the Albert Kahn Center, the French Society of Photography, The Lumière Institute, the Library of Congress and the National Geographic Society in Washington DC.

Lead photo credit : A family in the rue du Pot de fer, Paris. Autochrome from Albert Kahn's Archives de la planète. 24 June 1914. Photo Credit: Stéphane Passet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

More in Autochrome Lumière, Autochrome photography, history, Lumiere brothers, photography

REPLY