Flâneries in Paris: A Book Lover’s Walk along the Seine

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the 38th in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

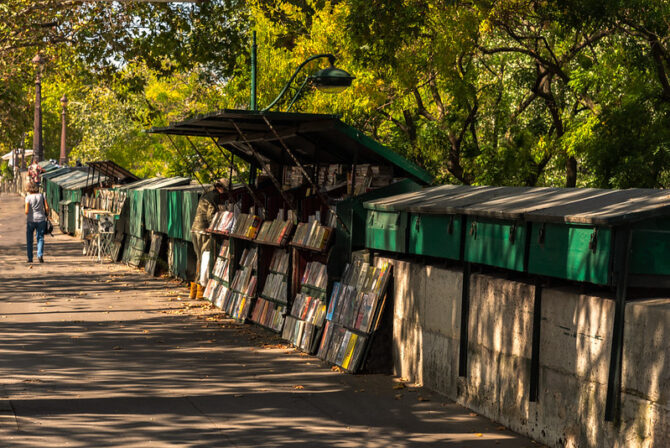

Paris: city of love, city of light, city of literature. It was this last aspect I had in mind for a little flânerie along the Seine, in search of things to appeal to the bibliophile in me. My route from the Institut de France, which houses the oldest public library in France, along the left bank to Shakespeare and Company, would have taken only 10 or 15 minutes if I hadn’t kept stopping. But there were so many things to look at or pop into along the way that a couple of enjoyable hours drifted by before I’d finished.

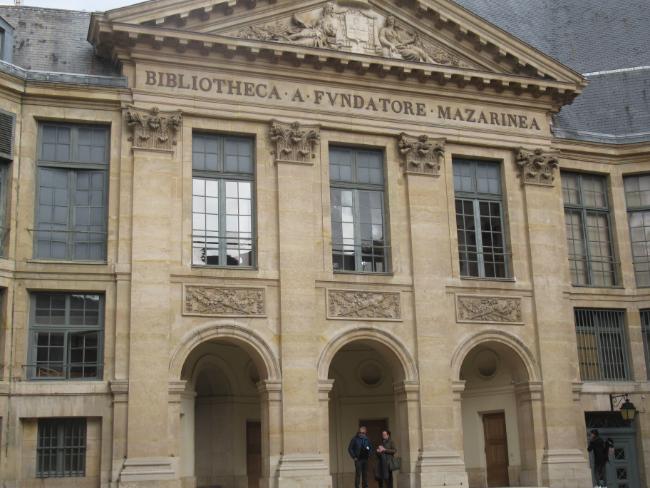

I started on the Quai de Conti, gazing up at the stately dome of the Institut de France, then headed through the entrance marked Bibliothèque Mazarine. I wondered if they really would let me in, but the wave of a passport as ID and a quick bag check allowed me through to the beautiful courtyard where a triple-arched entrance at one end was handily inscribed in Latin, explaining that it was Cardinal Mazarin, Chief Minister to Louis XIII and XIV, who had founded this scholarly haven: Bibliotheca a fundatore Mazarinae. I walked straight in, up the marble pillared staircase and into the hushed atmosphere of an academic library.

High wooden shelves lined the walls and all down each side sat the sculpted heads of admirable scholars, each mounted on its own pedestal. Here were the Roman emperors, Caracalla and Hadrien, alongside Cardinal Richelieu and Benjamin Franklin, each one adding to the learned ambiance. Leather tomes with golden lettered titles filled the shelves and all around the room academic magazines and publications were displayed. Volume L No 99 of “Papers on French 17th Century Literature” hinted at the depth in which topics are covered. A headline in the Revue des Musées de France informed me that the Louvre had just made a new acquisition and was now the proud owner of the Duc de Choiseul’s snuff box.

Practically every place at the study tables was full and about a hundred mainly young people were engrossed in research, leafing through books or hunched over computers and tablets in an atmosphere of quiet concentration. I was amused to spy a few rule-breakers, texting, whispering and in one case – quelle horreur – chewing gum. I thought of Cardinal Mazarin, who had returned from a posting to Rome in 1640 with 5000 books and later employed a librarian to scour Europe, buying up entire collections from other libraries before commissioning this building to house them all. Eager to share his treasure, he opened his collection to other scholars, thereby creating the first public library in France.

Bibliothèque Mazarine. Photo: Marian Jones

As soon as I left the tranquility of the library, two jarring notes yanked me back to the 21st century. Someone (possibly one of the studious library users I’d just seen?) had expressed their thoughts in neon spray all over the paved entrance to the Institut de France. Fluorescent green and garish yellow clashed with radioactive purples and pinks, but the writer’s key thoughts remained a mystery. The combination of French handwriting and slang meant I could not decipher what had got them so enraged. As I turned right along the quai, a combination of Ambulances Saint Germain and vans from the Gendarmerie flashed past, their blue lights and wailing sirens another reminder that rarified near silence is not the norm in modern Paris.

Courtesy of the Monnaie de Paris. Photo: Gilles Targat

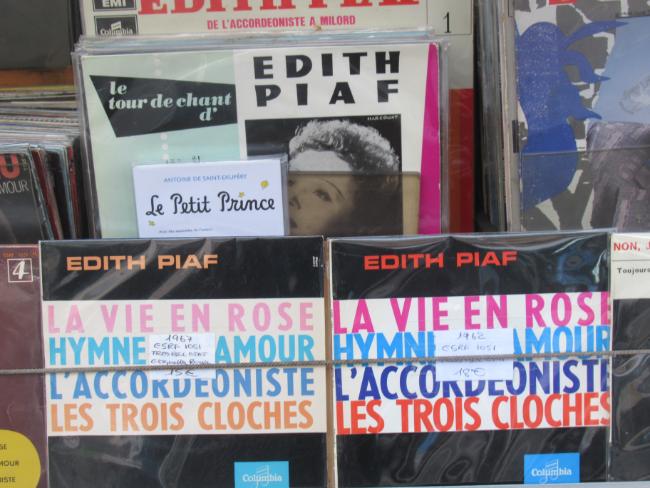

My route took me past the imposing Monnaie de Paris, today’s version of the national mint, established – almost unbelievably – in 864 by the wonderfully named Charles le Chauve (Charles the Bald). One day, I’ll go back to see its collection of coins and medals through the ages, including those struck for last year’s Paris Olympics. Today however, my focus was on literature and so it was disappointing to find that the first few bouquiniste stalls I passed were shuttered. Then came a stall whose weather-beaten owner had carefully laid out some French classics to attract attention. There were more vinyl records – Edith Piaf’s L’Hymne à l’Amour, a set of Françoise Hardy singles – than books, but I did spot a prominently displayed copy of that favorite childhood read, Le Petit Prince.

A cheerful young Irish man, minding the next stall for a friend, was happy to chat about books set in Paris and told me every word of George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London rang true, adding that he should know because he was really a waiter, not a bookstall owner. If I enjoyed that, he advised, I should get hold of Edward Chisholm’s A Waiter in Paris, published some 90 years later and “proof” (he claimed) that not much has changed. He had a few more reading recommendations, plenty of ideas on lesser-known Parisian sights for me to visit and views on diverse topics including Oscar Wilde in Paris and how Dublin compares with the city of light, then he bade me “Slán leat” which I found out later is Irish for goodbye.

Rue de Nevers. Photo: Marian Jones

The side streets off to the right were an eclectic mix. The narrow and eerily quiet Rue de Nevers led away from the quai, home to a fusty little jeweler’s shop whose window sign stated firmly “Mornings only, by appointment.” On the corner of Rue des Grands Augustins, named, I presume, after the Augustinian Order, was a jaunty restaurant called Lapérouse whose sign announcing that it has been a maison de plaisir since 1766 sat oddly with the poverty and chastity vows of the aforementioned monks. Its decoration had an art nouveau flavor with wrought-iron lanterns and feminine portraits, its various painted signs advertising cuisine et vins and their seafood speciality of produits de mer.

Laperouse. Photo: MBZT/ Wikimedia commons

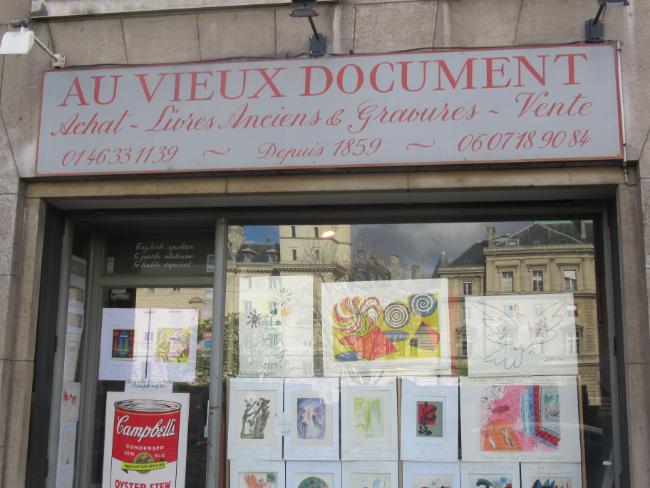

Among the little galleries and wine bars I passed were various antiquarian bookshops. The Librarie des Neuf Muses had nothing on display in the dusty window except a sign with a phone number for those who’d like to make enquiries. The sign above the nearby Au Vieux Document announced that they bought and sold old books and engravings, yet when I peered through the window and saw a man leafing through an enormous pile of old papers at his desk, I found it strange that he didn’t even look up. In a shop where customers seemed lacking, I thought the appearance of one might rouse his curiosity, but no. However, the shop has been there since 1859, so I guess they are managing somehow.

Au Vieux Document. Photo: Marian Jones

Next, I stopped at the Place St Michel to admire the fountain, resplendent with its statue of the Archangel Michel, dating, said the plaque in Latin, from MDCCCLX. 1860 then, part of the Haussmannian enlargement of this riverside square. It was paid for by the city of Paris and dedicated, ran the inscription, to Emperor Napoleon III, then in the middle of his 18-year reign. I’d read that originally, the central statue was to be of Napoleon, but perhaps that was deemed too imperial for the soon-to-be-republican times because eventually they opted for St Michael fighting the devil instead.

A bit further along was a branch of Gibert, a favorite haunt of Parisian students hoping to buy or sell second-hand books. Bargain-hunters are drawn to the sign which reads la librarie des petit prix: “the bookshop with low prices.” Here they can rifle through the boxes displayed outside on the pavement, one full of works on the environment, another rammed with well-thumbed paperback classics. Bold slogans remind customers that the second-hand market is “ecological” and “better for your wallet” and promise “more low prices inside.” Gibert is a reminder of a past era, a little fight-back against the digital dominance taking over our lives. I love it and I stop for a rummage every time I pass.

Gibert. Photo: Marian Jones

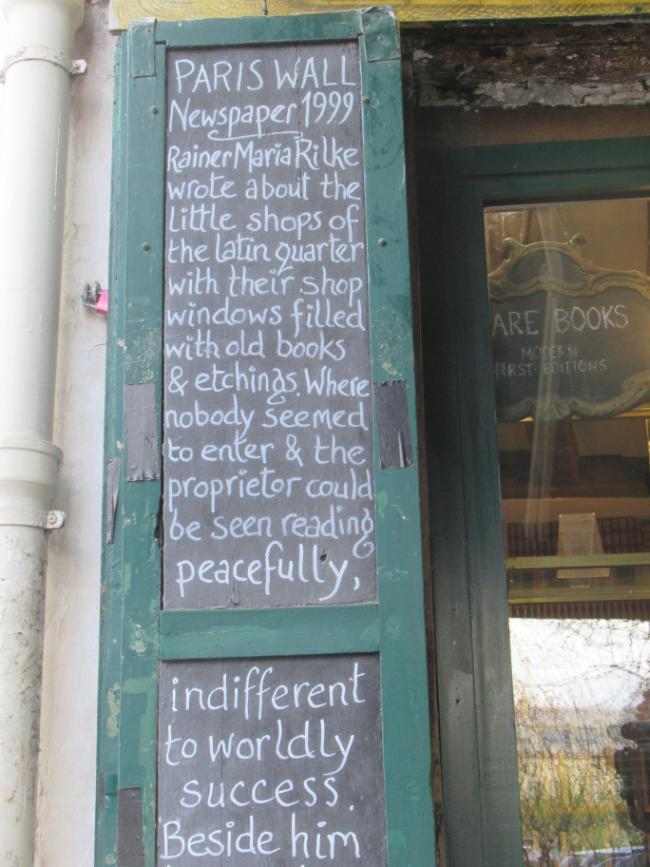

Shakespeare and Company in Rue de la Bûcherie, set just back from the river and opposite Notre Dame, was the end goal of my book-lover’s walk. I have written in a previous flânerie about the delights of its ramshackle interior, so instead of repeating myself, let me end with one of the anecdotes chalked up on the blackboards crowded onto its shop front. It quoted the German author Rainer Maria Rilke describing “the little shops of the Latin Quarter, with their shop windows filled with old books and etchings, where nobody seemed to enter and the proprietor could be seen reading peacefully, indifferent to worldly success.” It may have been written at the turn of the last century, but it was a fitting summary of the walk I’d just completed.

Practical information:

Shakespeare and Co. Photo: Marian Jones

Lead photo credit : Bouquinistes. Photo credit: Claude Attard/ Flickr

More in books, Flâneries in Paris, Seine