Book Review: A Waiter in Paris

One of the books I’ve used in every one of the classes I taught in my CUNY summer study abroad program in Paris through the years is George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London. This classic, slightly fictionalized account of Orwell’s experiences living in Paris in 1928-29, including his work as a dishwasher in a “smart” hotel, and then as a waiter in a Russian restaurant, is one good way of balancing the romantic myths of Paris with one of its realities — the lives of the working poor who keep the wheels turning in the City of Light.

Despite Orwell’s shocking (and shockingly casual) use of anti-Semitic language I have always loved this book because of the light it sheds on the plight of the working poor, and for the incisive social/political analysis he applies to what he observed during the 10 weeks during which he had a good look at those realities close up.

No doubt hotels and restaurants must exist but there is no need that they should enslave hundreds of people. What makes the work in them is not the essentials; it is the shams that are supposed to represent luxury…Essentially a “smart” hotel is a place where a hundred people toil like devils in order that two hundred may pay through the nose for things they do not really want. If the nonsense were cut out of hotels and restaurants, and the work done with simple efficiency, plongeurs might work six or eight hours a day instead of ten or fifteen.

Although he never says so directly, it seems that Orwell decided to take the opportunity presented to him when he accidentally fell into poverty to tell the rest of the world what was like — partly because he could see that the people in the endless, grinding cycle of the trap they were caught in would never be able to do so themselves.

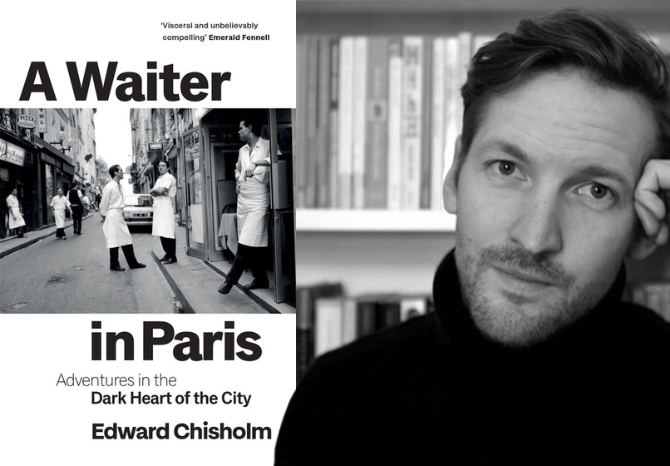

Of course one might imagine that nearly a century later, given the social safety net in modern France, the world Orwell described no longer exists. And indeed there are better protections for workers in France today. And yet — with Edward Chisholm’s A Waiter in Paris: Adventures in the Dark Heart of the City, published just last year, we are given the opportunity to see what the world behind those swinging doors is like now. And it’s hardly a bed of roses.

It is natural that Chisholm’s book would be compared to Orwell’s Down and Out, and it has been. The comparison is apt: both were penniless young aspiring British writers at the time they experienced working in Paris restaurants. Orwell had come to Paris at age 25, after resigning from the Indian Imperial Police. (He wrote later that he had resigned his position “to escape not merely from imperialism but from every form of man’s dominion over man.”) Chisholm was also in his early 20s when he came to Paris in 2011, after trying and failing to find a professional position for himself in London in the wake of the global financial crisis. For both, a memoir about the underside of the restaurant business in Paris was their first published book. And both of these works provide an incredibly detailed, often shocking look at the inside of a world most middle-class people never see and could hardly imagine. Both writers also force readers to not only see what they saw, but also to think about why such conditions exist, and consider whether all of us are complicit in the drudgery and just plain hellishness of it to some degree: at least to the degree of closing our eyes to it. And both are extraordinarily well written.

Edward Chisholm

Yet there are significant differences. One of the differences is that Chisholm sets a goal for himself to not only become a waiter, but to be accepted into the fraternity of the waiters, runners, and kitchen workers he found himself working with in a “smart” restaurant. To be sure, this was an unstable and frequently shifting fraternity, and not a fraternity of the whole staff — but there was within that closed world a meaningful fellowship of true understanding of and loyalty to one another. And Chisholm was eventually accepted into that circle of friends.

Because he stayed in that world for much longer than Orwell did — nearly a year, compared to Orwell’s 10 weeks — and because he really worked at developing real, substantive friendships with his coworkers, we learn much more about them than we do about the characters who people Orwell’s Down and Out. There is the aspiring actor reaching the age where his aspirations are becoming less and less likely to be realized; the middle-aged waiter who has no greater ambition than to marry the love of his life and provide their daughter with a secure present and future; the foreign ex-Legionnaire whose past life is a source of endless speculation among his coworkers; the disdainful sommelier who grudgingly agrees to teach Chisholm about wine once he sees that his interest in the subject is genuine (eventually he too becomes a friend).

Chisholm encourages, even helps some of his coworkers to pursue the dreams they confide in him, and they in turn encourage him in his. (“Do us all a favor,” one of them says to him one night, in a moment of drunken candor. “Get out, show us how it’s done; give us some hope. Write, I mean it.”)

One night shortly before he leaves the restaurant, as he falls asleep exhausted, Chisholm reflects:

I promise myself that I will leave the restaurant. That I must leave. I must find a way out. I understand that I’ll never be as good as the others at waiting; it’s not me. But I’ve proven to myself what I came to prove: I can do it, I know how to wait, I know how to work. Now I have to prove something else, that I can write. That I can tell people’s stories. That is what I must do—tell these people’s stories.

In the coda to the book he adds:

Of course I know now that I was never truly in the same situation as the characters I met and worked alongside—I was merely a spectator passing through on the way to somewhere else, even if at the time I didn’t realize it. My being there was part economic reality in a post-financial-crisis world, and part belief that by perhaps going and actually doing something, by living my life differently from what was expected, I could succeed at what I believed in: to experience something truthful and to write something of genuine meaning.

This final goal — to write something of genuine meaning—is so very well realized in this book. It is a deeply moving work of exceptionally beautiful prose. It is thought-provoking and heartfelt and extremely engrossing. It is funny, sad, and fascinating —fascinating, among other things, to see how this middle-class university graduate was able to persist in learning to be a waiter, and not give up at one of many points along the way where most people would have. It is a collection of compelling stories about what goes on in a world most of us will never experience — a world that most of us, to be honest, would not want to.

Last, but certainly not least, it introduces us to a handful of admirable human beings we will never have the chance to know — human beings who are worth caring about, and who represent so many others in similar circumstances who are worth caring about also.

What are we to do with the experience of having read it? I don’t think I can say it any better than Edward Chisholm himself has said it:

If there’s one thing to take away from this book, I hope that it is this: the next time you’re eating something that seems too good a value to be true, spare a thought for the people who are paying the real price. And, if you can, spare them some of your change too.

You can find our Bonjour Paris Live event “A Waiter in Paris” featuring Edward Chisholm on our video hub and you can buy the book below.

Lead photo credit : A Waiter in Paris