Flâneries in Paris: Explore Montfort l’Amaury

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the 36th in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

I went to Montfort l’Amaury, a picturesque little town about 30 miles west of Paris, to visit Maurice Ravel’s house. There was no flânerie planned, just a quick walk up the main street in search of lunch. But I was charmed by the bright sunshine, the little town on the edge of the Forest of Rambouillet and the stunning views which opened up around it as I gained a little height. I just had to linger, explore and pause to listen to voices from 1000 years of history, so in the end I spent the whole afternoon there.

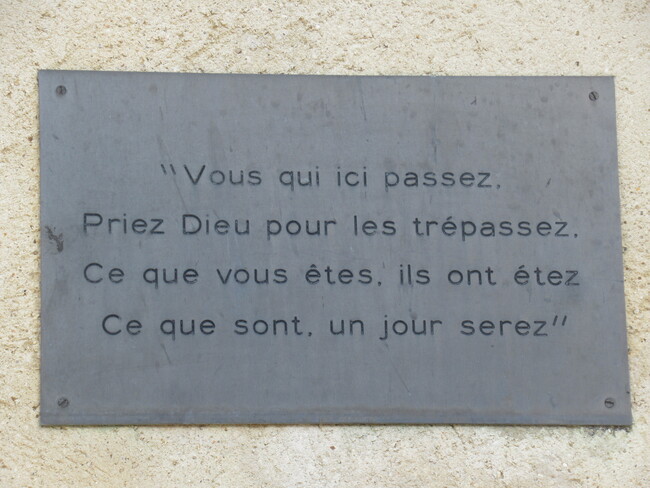

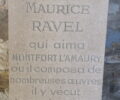

At the cemetery, the somber message on a plaque over the entrance contrasted with the spirit-lifting bright blue sky above me. It read, “what you are, they once were, what they are you will be one day.” Eeek. It’s a crowded space, with a jumble of graves set against a backdrop of pretty cottages beyond the walls. Around two edges are cloister-like covered walkways where inscriptions on the walls indicate that there are graves here too. At the far end sits a bust of Maurice Ravel, who lived here for the last 16 years of his life and, as is inscribed in French on the plinth beneath, “loved Montfort l’Amaury, where he composed many of his works.”

I followed the Rue Saint-Nicolas along the back of the cemetery and round towards the grassy mound where the castle used to be. On the way up, a lovely view opened up of the church, framed by trees, which has watched over the town since the 15th century. After a couple more twists of the little pathway, what’s left of the castle suddenly appeared, two stone towers rising defiantly against a deep blue sky, reminding me that when my countrymen, fighting for Henry V, attacked the chateau during the 100 Years War, they didn’t quite obliterate it.

My thoughts were interrupted by a lady sunning herself on the grass. Bonjour, she smiled, tilting her face upwards. This splendid weather suits me, she explained, stretching out her arms and continuing, “I am recharging my batteries, reloading my solar panels.” I wondered aloud why the towers are named after Anne of Brittany. Ah, she said, that’s because it was Anne who had the castle rebuilt after – and here she peered at me accusingly – l’invasion. Had she guessed my nationality from my accent? I told her Henry V died, it’s thought of dysentery, just a year or two later at the Chateau of Vincennes and she smiled. Entente Cordiale restored!

I found out later what happened to Anne’s new version of the chateau. It too was destroyed in the early 1800s in an attempt to blank out the atrocities which happened there in revolutionary period known as the Terreur. About 80 insurgents, opposed to the new regime, were imprisoned here and many of them never got out alive. It was hard to imagine these horrors happening here on this tranquil spot, especially on such a perfect day.

The mound is 185 metres above sea level and the views are stunning. I came upon an unexpected sighting of Le Belvédère, the charming little house where Ravel lived. From above, the slate “witch’s hat” atop the central tower stood out and I thought back to all the quirky corners I had seen inside it that morning. The decoration, which the composer had curated himself, was an artistic mix of browns, creams and gold, a setting for the kitsch ornaments he loved to collect – pottery animals, brightly painted crockery, a musical box designed as a little bird in a golden cage. He was reserved, mixing mainly with just a small group of friends, but he obviously had a sense of fun. I left his house rather wishing I’d been able to meet him.

On the way back into town I came across another intriguing character, Anne of Brittany, who was Countess of Montfort l’Amaury before she married first Charles VIII and then Louis XII and became Queen of France twice over. I found the rather shabby plaster mould of her quite underwhelming, but discovered later that the original bronze statue was destroyed in World War II. Nevertheless, Anne’s serene gaze hints at her cultured intelligence, her love of tapestries, illuminated manuscripts and music. Perhaps there’s also a hint of sadness for the many children she lost, for she bore at least 11, only two of whom survived into adulthood. I hope one day someone will replace the plaster cast with the bronze version she deserves.

I walked back to the center of town, past lop-sided half-timbered houses and businesses named with the town’s heritage in mind. An estate agent was called after la Duchesse Anne and the name of the restaurant where I’d lunched, Le Bistrot des Tours, paid homage to the towers she had left behind. It all led up to the Place de la Libération, dominated by the church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, built under Anne’s direction in the early 1500s. The front is solid and rather plain, but stretching back down each long side is an amusing surprise, a whole row of gargoyles leaning out over the street and pulling faces.

Inside the church, sunlight streamed through the high stained-glass windows, bright shafts of color bequeathed to us by 16th-century craftsmen. I found a wealth of stories: how these windows, among the first in France to use new and beautiful shades of blue and purple, were the reason the church was designated a monument historique; how brave souls continued to worship secretly during the revolution, when Ursule Thierrier, a mother of five, was guillotined because she had welcomed catholic priests into her home; how the church lay empty during the terreur and services only resumed in 1805, a moment celebrated with the installation of three new bells; how more than 20 local men lost their lives in the First World War and more than twice that many in the Second.

My walk around the rest of the town center took me over cobbled streets and past ramparts, built in the 11th century and rebuilt by the townspeople after their destruction during the Hundred Years War. I saw the Auberge des Trois Chandeliers where dashing Henri IV once stayed, and picturesque properties with connections to celebrated authors like Victor Hugo and Jean Anouilh. I went through a tiny passageway which once housed a communal bread oven and passed the Hôtel de Ville where Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité was writ large and a plaque recalled the 18th of August, 1944 when “Montfort l’Amaury was delivered from Nazi occupation by the American Army.”

To me, Montfort l’Amaury was a little haven, really totally unlike anything in the big city just half an hour’s journey away. The medieval streets and the plaques displayed on so many buildings made connections to the past. History, it seemed, was everywhere. Later, I discovered that Victor Hugo, who visited a number of times, felt the same and expressed it in a poem which begins, “I love you, ruins, especially in autumn.” In it, he recalls sitting up on the hill by the remains of the chateau, imagining scenes from the past. He pictures – I’m paraphrasing – the castle’s murderous arrow slits and the knights of old, very aware, as he puts it, that warriors once died on the same grassy spot where he is watching children play.

Victor Hugo’s poem was written in 1825, yet the feeling he described was precisely how I felt, surveying the same scenes exactly 200 years later. I had “met” so many people from bygone eras in my short afternoon of exploring that I had to agree with him: in Montfort l’Amaury the past is really not that far away.

This walk was based on a leaflet, A Cultural Walk through Montfort l’Amaury, available in French and in English from the town’s Tourist Office at 3, Rue l’Amaury.

Visits to Ravel’s house are by prior arrangement only. Email [email protected] to enquire.

Lead photo credit : Ravel's house. Photo: Marian Jones

More in Flâneries in Paris, Maurice Ravel, Montfort l’Amaury