Ice Skating to ‘Bolero’ and the Brilliance of Composer Maurice Ravel

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

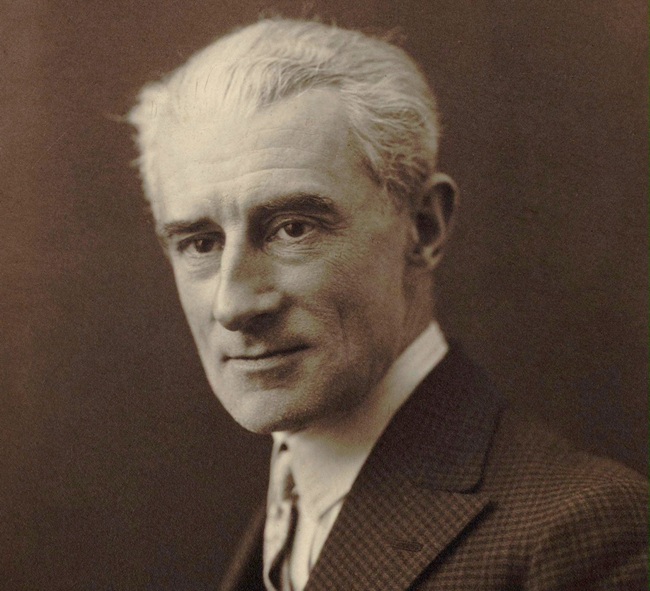

As we commemorate the 150th anniversary of Maurice Ravel’s birth, Anne Price takes a look at the life and work of the Symbolist composer who thought outside of the box

On March 7th, 1875, almost a year after the first Impressionist exhibition was held in the studio of portrait-photographer Nadar, Joseph Maurice Ravel was born. He would become, along with his older contemporary Debussey, a leading Impressionist/ symbolist composer. Paris in the 19th century was an exciting time for the artistic and literary world. Inspired by the likes of Delacroix, Monet, Baudelaire and Mallarmé, artistic movements such as Impressionism — followed in quick succession by Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, Expressionism, and Modernism in the 20th century — caused shock waves among the artistic elite. Music trailed visual artists and poets by a generation before acquiring the term “Impressionism,” which became a generic moniker for the avant-garde movements of the last decades of the century.

Maurice Ravel in 1925. Author unknown. Public domain.

Ravel’s father, Pierre-Joseph Ravel, was an educated, successful engineer and entrepreneur who came from Versoix near the Franco-Swiss border. Ravel’s Basque mother Marie grew up in Madrid. Although less educated than her husband, she was intelligent and free-thinking. The family moved to Paris when he was three months old. Ravel recalled that music was very much a part of his childhood, crediting his parents for stimulating and developing his musical interest from an early age.

When he was seven, Ravel started piano lessons with French pianist and composer Henri Ghys. At 12, he began studying harmony and composition with Charles-René, who urged Ravel’s father to send his son to the Paris Conservatory. At 14, playing music by Chopin, he was admitted as a piano student into the Paris Conservatory. Two years later, he went on to win first prize in the Conservatory’s most esteemed piano competition, but for someone who came to be regarded during his lifetime as France’s greatest living composer, it was not an easy journey.

Charles de Bériot’s class at the Paris Conservatoire, circa 1895. Ravel stands on the far left. Photo: Eugène Pirou — Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public domain

After such a prestigious start, he struggled to establish his reputation against some of the most influential names in the musical hierarchy. Ravel recognized that he was not as good a pianist as his colleagues Viñes and Cortot, believing that constant practicing dulled his creativity. This determination to learn on his own terms meant he gained no further prizes, leading to his expulsion in 1895. Despite what the Conservatory thought, his art flourished during those early years.

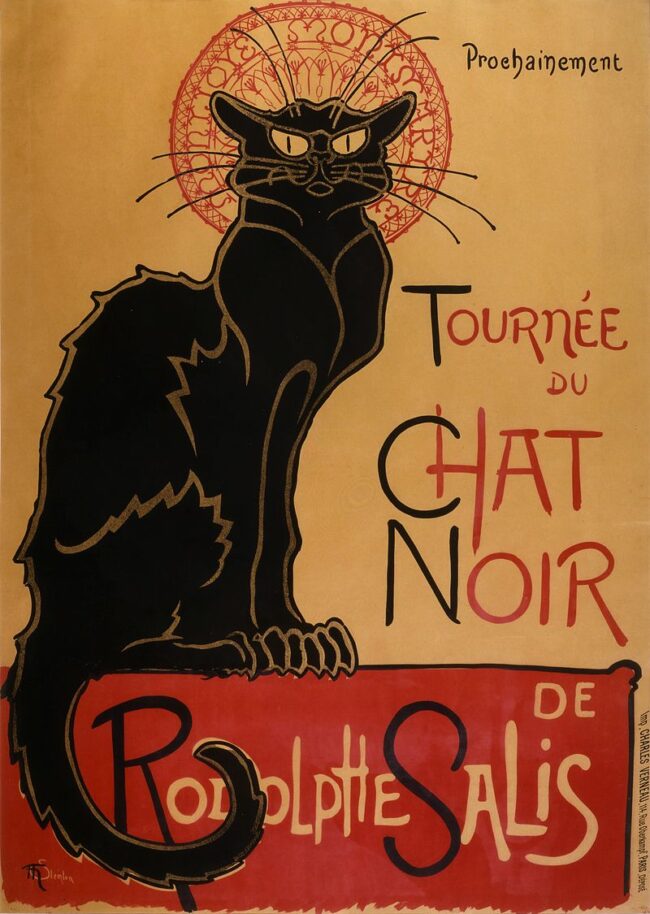

In 1891, while he was still a piano student, he composed Jeux d’eau (Play of water) regarded as one of the first great Symbolist works for piano. His father introduced him to Erik Satie, who had also been a student at the Conservatory, and like Ravel, had been dismissed for not winning any prizes. Satie, who was earning a living as a café pianist playing at Le Chat Noir, inspired Ravel with his unorthodox music and it was Satie who taught him to think outside the box.

Théophile Steinlen’s 1896 poster advertising a tour to other cities (“coming soon”) of Le Chat Noir’s troupe of cabaret entertainers. Public domain

In 1897 Ravel was given a chance to achieve his overriding ambition to be a composer, with his readmission to the Conservatory to study composition with Fauré, under whose guidance he composed some of his best pieces, including the Shéhézérade overture, the first performance of which he conducted in May 1897.

Fauré described him as having an “engaging wealth of imagination.” It was not enough to win him any further prizes and he was dismissed again in 1900. As a former student of the Conservatory, he was allowed to sit in on Fauré’s lessons and with Fauré’s encouragement, he tried for France’s most prestigious prize for young composers, the Prix de Rome. Between 1900 and 1903, he won only one prize, finally giving up on the Conservatory, recognizing that he had other avenues open to him.

In 1905, he decided to try the Prix de Rome once more. His elimination in the first round, which even his most persistent critic Pierre Lalo denounced as unjustified, led to a scandal, known as L’Affaire Ravel, resulting in a radical reorganization of the Conservatory, amid accusations of favoritism amongst the judges.

While Ravel’s music is passionate and distinctive, the man himself remains an enigma. Described as a brilliant, ironic, self-controlled, and shy person, he never married, saying that artists were not made for marriage as they were not normal and did not lead normal lives.

He enjoyed the company of others and he was completely faithful and loyal in his friendships. He used to say, “One does not prove he has a heart by simply opening up his chest,” which makes it all the more difficult to see how Ravel could ever have had any connection with the frivolity of Saint Valentine’s Day.

Most people associate the day with Eros who, according to Greek poets, was a handsome immortal who played with the emotions of gods and men by using golden arrows to incite love. It is celebrated on February 14th. On that date in 1984, British figure skaters Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean won the figure-skating gold medal at the Olympic Winter Games held in Sarajevo that year.

Figure skaters at that time edited together three different pieces of music, with varying moods and speeds. Being too different made participants vulnerable to subjective judging, something with which Ravel would have been all too familiar. Ice-dancing’s traditional ballroom roots were still preferred to the new, looser, dramatic, romantic style which was thrilling the crowds. Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean wanted to create something truly captivating.

“Maybe it was a risk in some ways but it was something we felt strongly about and believed in,” they said, referring to their choice of Maurice Ravel’s Bolero as the piece of music to which they would perform their free dance. “Bolero has one constant rhythm all the way through, with a continuous flow, a building crescendo and a dramatic climax. It is a single piece of music, with a single repetitive theme musically and yet it just builds and builds emotionally. That is what we wanted to do on the ice, build to a climatic end,” they explained. “Bolero is a very hypnotic and romantic piece. In our heads anyway, it is a love story.”

Torvill and Dean performing in 2011. Wikimedia commons

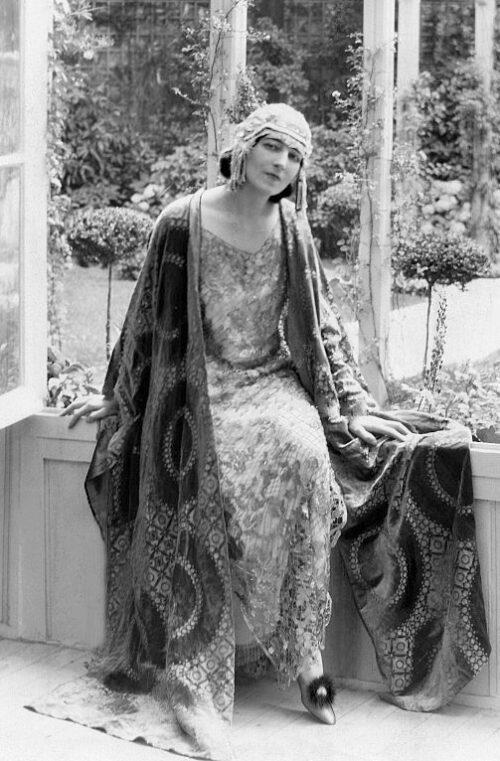

Ravel wrote Bolero almost 60 years before. It was not planned and he could not have predicted it would become synonymous with figure skating. Dance and theater icon Ida Rubinstein had asked him to write a ballet score with a Spanish theme. He could not get the rights to orchestrate six pieces from Isaac AIbeniz’s work, Iberia, so he had to compose something himself. He conceived the idea of a theme that was less than a minute long but repeated as long as necessary, taking inspiration from memories of the throbbing rhythms of the machines in his father’s factory and the melodies of Spanish lullabies of his childhood, sung to him by his mother.

He was astonished at its success, which was due partly to Ida Rubinstein’s sensual, provocative, 18-minute performance surrounded by 20 male dancers whom she lured seductively to the music’s climax. When an elderly member of the audience at its premiere in the Opéra, shouted, “rubbish!” he remarked, ‘That old lady got the message.”

Dancer Ida Rubinstein in 1922. Author unknown. Public domain

Ravel’s Bolero seems to encapsulate what Spanish writer and musician Federico Garcia Lorca referred to as the “duende,” which he described as “the spirit of the earth” and a heightened state of emotion, expression and authenticity, often connected with flamenco. Lorca saw all arts as capable of duende, but it finds its greatest expression in music, dance and spoken poetry, being as free and fluid as possible – something which, accompanied by Ravel’s composition, figure skaters Torvill and Dean achieved.

The musical score was reduced to four minutes, but their performance evoked the same strong, emotional response as, 60 years before, Ida Rubenstein had done in her performance, but by seductively luring the audience and the judges rather than 20 young males. Since then, Bolero has been used as film scores and played in jazz and rock clubs. Francois Reyes, a member of the Gypsy Kings, sings Spanish lyrics to Bolero on his first solo album of which it is the title track, and it has been used in productions of Lorca’s Blood Wedding.

There is nothing to say that Ravel and Lorca met personally, but they would certainly have been aware of each other. Lorca was a gifted musician and piano player, his musical training coming before any other. Ravel regularly hosted the meetings of a group of innovative young artists, poets, critics, and musicians formed in 1900, called the “Apaches” (Hooligans), a name coined by Ricardo Viñes to represent their position as “artistic outcasts.”

Lorca’s close friend and piano teacher Manuel de Falla was a member and attended the meetings during which they would hold intellectual arguments and perform their latest works. Lorca’s passion for music marked his entire life, and it is almost certain he learned of these meetings from de Falla. It is not inconceivable to think that when Lorca was in New York with the university theater group Barraca in 1929, he would have found time to see the performance of Bolero at Carnegie Hall.

The passion, drama and sensuality of Spanish music had already been instilled in Ravel by his mother who, in his childhood, sang to him songs from her Basque-Spanish heritage. It was revived in him by the young Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes. They met in 1888 when they were both 13. Like any young musicians today who feel passionate about their work, they would spend hours together experimenting with new sounds on the piano. Ravel and Viñes remained lifelong friends, learning from their close friend and adviser Chabrier, and sharing an interest in the writings of Baudelaire, Mallarmé and Wilde. Ravel set several of Mallarmé’s poem to music and he credited Poe with being his teacher in composition after analyzing repetition in The Raven, an influence apparent in the rhythmic repetitiveness of Bolero.

Musicians gathering at Mr. Godebski’s by Georges d’Espagnat (1910, Paris, Bibliothèque-musée de l’Opéra). This painting shows Cipa Godebski and his son Jean at their home at 22 rue d’Athènes in Paris, surrounded by musicians from the Apache circle, including Ricardo Viñes (at the piano) and Maurice Ravel.

Throughout his career, Ravel appeared genuinely indifferent to blame or praise. The only opinion of his music that he truly valued was his own. He was a self-critical perfectionist and had a strong vision of his music. His friend and biographer Alexis Roland-Manuel wrote, “He is intelligent, open, and natural in everything he says. He judges himself and others with a strong desire for impartiality and a clear-sightedness which is quite rare in an artist.”

It was this clarity of thought which led him as a young student to begin to question the Conservatory’s traditional, conservative way of teaching and ultimately led to his dismissal. Undeterred, he went on to be regarded , after Debussey’s death, as France’s leading composer, a source of great pride for his old tutor, Fauré, who wrote to him, “I am happier than you can imagine about the solid position which you occupy and which you have acquired so brilliantly and so rapidly.”

Le Belvédère in Montfort-l’Amaury, where Ravel lived from 1921 until his death. Photo: Reinhardhauke /Wikimedia commons

His accomplishments were many but he remained staunchly reserved about his private life. He loved his family, his friends ,and his music and was a truly remarkable man. Extremely distressed by Germany’s occupation of France, he tried to join the air force but was turned down because of his age and a minor heart problem. Undeterred, in March 1915, when he was 40, he joined the 13th Artillery Regiment as a lorry driver, often putting himself in great danger. His friend Stravinsky expressed admiration for his friend’s courage saying, “at his age and with his name he could have had an easier place, or done nothing”. In 1920 he declined the offer of the Legion of Honor.

The idea of “doing nothing” was not something Ravel ever entertained. He wrote music for piano, chamber music, two piano concertos, ballet music, opera and song cycles. In 1932, he suffered a blow to the head in a taxi accident which left him unable to write music or perform, although he could still hear music in his head. He died five years later on December 28th at the age of 62. His house at Montfort-l’Amaury became a museum and remains open for guided tours.

Lead photo credit : Maurice Ravel at the piano on March 7, 1928 in New York, during a party organized in honor of his 53rd birthday. Behind him, from left to right, conductor Oskar Fried, Canadian singer Éva Gauthier, Manoah Leide-Tedesco and George Gershwin. Public domain

More in Bolero, ice skating, music, Ravel

REPLY