The Mysteries of Jim Morrison’s Paris

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the legendary rock group The Doors. In honor of the anniversary, the city of Paris is naming a footbridge (passerelle) after the band’s front man, the even more legendary Jim Morrison. The footbridge crosses the Arsenal port (ie marina) of the Canal Saint Martin near the Bastille. (It’s more precisely situated at rue Mornay, between Boulevard Bourdon and Boulevard de la Bastille.) Access is closed during a year-long sprucing-up of the footbridge, which is due to open in February 2026. You can approach it, however — the impressive structure looks like a miniature, metallic railroad trestle. With an extensive paint-job and new concrete and wooden flooring it should look terrific when completed. (The renovation will also eliminate traces of lead from the old coats of paint.)

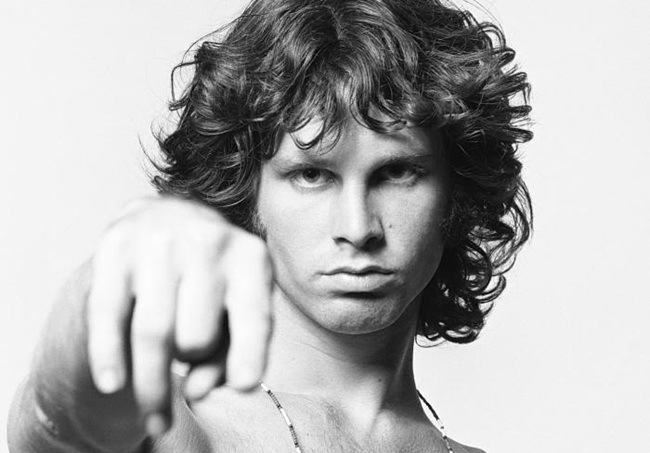

The footbridge was built in 1825, and was called the “passerelle Mornay” after the street but had no official name. Two hundred years later, the Paris city council decided to name the footbridge after Morrison, whose renown carries a special vibe in the city. The Doors’ sensual yet otherworldly sound still resonates decades after his premature death, and the singer’s deep, strong voice, and the echoing strains of Light My Fire, Ghost Riders of the Sky, Riders on the Storm, End of the Night, Crystal Ship, among others, are instantly recognizable. Morrison’s iconic image on posters, t-shirts and whatever else, for sale in dozens of gift shops on the Left Bank, easily gives Marley, Hendrix, Tupac, Cobain and even Barack Obama a run for their money.

The passerelle Mornay, now named after Jim Morrison. Photo: Mbzt/ Wikimedia commons

The crystal ship is being filled/a thousand girls/a thousand thrills

To some, The Doors bring to mind California. The group was founded as a result of a chance meeting of Morrison and keyboardist Ray Manzarek at Venice Beach, and one of their songs (and an album) is titled “L.A. Woman.” But The Doors and especially Morrison are inextricably linked to Paris as well (he also composed a song called “Paris Blues”). This is where he finished his life, in the Marais district that he loved, and where his remains repose, at Père Lachaise cemetery. The footbridge, as it happens, isn’t far from either.

As sensory and sensual as the songs could be, and with all the carousing he was prone to, there was something about Morrison’s life and death that evokes Shakespeare’s “stuff dreams are made of.” The band’s name came from the “doors of perception,” an expression coined by the great mystic poet and artist William Blake (and the title of a cult book by Aldous Huxley, an author interested in both mysticism and psychedelics). Their music was inspired not only by Blake but French visionaries like Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud. Manzarek has said that the moment after they completed “Riders on the Storm,” he had a premonition that Morrison was going to Paris. In addition, Morrison was an archetypal rebel whose anti-establishment gestures got him into trouble. He was charged with indecent exposure (on stage) in Miami, another reason he came to France. (He was pardoned posthumously.) He came to Paris in March 1971.

Break On Through to the Other Side

Morrison’s romantic vision featured metamorphoses from one state of being to another, as in the song “Break on Through to the Other Side.” He called himself (or was called) the Lizard King, and underwent his own transformations. In Paris he’d wanted to change from rock star to writer like his heroes Rimbaud and Blake. He also turned into a poète maudit at the end of his tether: He put on weight, grew a beard, became alcohol- and drug-addled. To some he was almost unrecognizable.

Many of the places in Paris that Morrison frequented also changed beyond recognition. Le Beautrellis, a traditional restaurant on the street where he lived, became a Morrison-themed hangout after his death, then a law office. L’Astroquet café, site of an impromptu jam session, became a hotel. The Rock n’ Roll Circus bar, where he may have OD’d, became Whiskey à Gogo. The Bar Alexandre became a Japanese bank. Les Fils Pervrier cheese shop on the rue Saint-Antoine is now a pizza joint. France itself was changing in the aftermath of May 1968 — Charles de Gaulle passed only a year before Morrison.

Our love’s a funeral pyre

Morrison didn’t come to Paris with his bandmates but he didn’t come alone, either. Pamela Courson was his most significant companion. Her father had been in the Navy, like Morrison’s. She was a beautiful adventuress, a heroin addict, and Morrison’s femme fatale. Literally: one rumor had it that Morrison accidentally ingested her stash of heroin, mistaking it for cocaine. He considered her his common-law wife, and she’d later go by Pamela Courson Morrison, yet they had an “open relationship.” She was notably involved with a French aristocrat and drug dealer. Shortly before his death they saw a film called Pursued (starring Robert Mitchum), in which the hero suffers in part thanks to a couple of femme fatale-types. Morrison didn’t care for the film; Pamela liked it. She inherited his entire estate though only lived a few years to enjoy it before she overdosed at age 27. Her family and Morrison’s fought over the estate before agreeing to split it. (Morrison was estranged from his father, an important admiral during the Vietnam War who later became active in overseeing his son’s legacy.)

Place des Vosges. Photo credit: Marko Maras/ Flickr

Strange Days

Morrison liked the rue Beautrellis, where he and Pamela sublet an apartment, and enjoyed walking over to the Place de Vosges to read or write. He also liked to relax on the Quai d’Anjou at Ile Saint-Louis. He hung out in other parts of Paris, such as Saint-Germain-dés-Prés, still a hub for intellectuals and artists. He preferred the Deux Magots, while Pamela preferred the Café de Flore (where her lover-dealer and his crowd hung out). He loved La Palette, an artsy café-bar in the 6th that I happened to frequent in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and that’s still going strong. L’Hotel, where he fell out of a window and survived unscathed, remains, as does Le Mazet, a favorite restaurant on rue Saint-André des Arts.

La Palette in the 6th. Photo: Sorin Popovich/Flickr

Can You Picture What Will Be?

Morrison had been a film student (like Manzarek) and had odd brushes with film. He was slated to appear in an Andy Warhol film but dropped out (his co-star would have been Valerie Solanas, who shot Warhol). In France he visited the set of the classic-to-be Peau d’Ane, directed by Jacques Demy. Pursued, the last film he saw (at the Action Lafayette cinema, closed in 1986), was a lugubrious “Western noir” about a survivor of a family massacre. Demy’s wife, the great New Wave director Agnes Varda, spoke at his burial, its only ceremonial aspect. In 1991, Morrison became the subject of an Oliver Stone biopic starring Val Kilmer (the surviving Doors disliked it). He had his own unrealized film projects, and brought short Super 8 versions with him to Paris, entitled Highway, Feast of Friends, The Doors Are Open

His one true contribution to film is in Apocalypse Now, where “The End” figures in a significant way. I remember the sneak preview in Manhattan, the 70mm print projected onto a huge screen: the surreal opening with gliding helicopters and silent explosions to the tune of “The End” is still one of the most unforgettable sequences I’ve ever seen. (The film was the subject of my first review, for a college newspaper.) It’s ironic that Morrison’s father was an admiral during the war — most of the film’s main characters are sailors on a Navy PBR (Patrol Boat, River).

Morrison and his father George Morrison on the bridge of the USS Bon Homme Richard, January 1964. Public domain.

No One Gets Out of This Alive

Morrison’s romantic vision was also obsessed with death: The End, End of the Night (inspired by Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s novel), Ghost Riders in the Sky, When the Music’s Over. Morrison’s own death was mysterious — like other famous rock icons he died at the age of 27. He was allegedly found in his bathtub in the rue Beautrellis flat, the death reported by Pamela. The coroner’s report stated the cause of death as a heart attack, but no autopsy was performed. There were reports he’d died of an overdose in the restroom of the Rock n’Roll Circus nightclub, and that his drug dealer transported the body home (there was a book to this effect written by the club’s proprietor). Marianne Faithfull, who’d been involved with the aristocratic dealer, corroborated this version.

He was buried in the fabled Père Lachaise cemetery, but his funeral was cheap and quick for such a prominent person. Only a handful of people attended. The tomb immediately became a shrine for his fans, constantly decorated, the decorations constantly graffitied over, damaged or stolen, then redecorated. As with many others, it was one of my first destinations on coming to Paris. Graffiti in the cemetery (disrespectfully painted on other tombs) pointed out Jim This Way. The tomb had a bust of Morrison perched on it, a real joint stuck in the mouth. Supposedly the grave is still the fourth most visited site in Paris.

Grave of Jim Morrison, Paris, France, Photo: Suzanne GW/Wikimedia Commons

People Are Strange

It might have been more appropriate if the footbridge had been named after The Doors as a collective, instead of just Morrison. They were always known as The Doors, never became, say, Jim Morrison and The Doors. The songs came out of a collaborative, improvisational process. (Manzarek provided insightful descriptions of the different ingredients that went into their magical brew.) Yet it’s true that Morrison provided the band’s lyrical heart and his voice was central to the songs, just as his physical presence was the molten core of the live performances. No great Doors songs came after his death. Although he wrote “Paris Blues,” he never performed here outside of jam sessions in homes and bars. It was the surviving Doors who later played at l’Olympia, the legendary venue for so many iconic performers, but not Jim. On his tomb his family inscribed the Greek KATA TON DAIMONA EAYTOU, which has been interpreted as either To the divine spirit within himself or He caused his own demons.

Street art depicting Jim Morrison, “This is the End,” by Jef Aerosol in Rue Mouffetard. Photo: KoS / Wikimedia commons

Lead photo credit : Jim Morrison. Photo: Dayan80/ Flickr

More in Jim Morrison, Père-Lachaise

REPLY

REPLY