Medieval Marvels at the Cluny Museum

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

It won’t matter if you are a bit hazy on the details of Charles VII who was king of France from 1422-1461. You will surely still love the exhibition on the arts during his reign which is running at the Musée de Cluny until June 16th. It is chock full of colorful medieval pieces, from large-scale royal tapestries to exquisite illuminated manuscripts, and if you wanted to wander and enjoy, rather than focus too much on the historical context, you would certainly find much to admire. Not that the history isn’t fascinating too, for it was Charles, backed by Joan of Arc, who wrested his country back from English rule and brought the 100 Years War to an end.

Art historians have sometimes commented that art was “of marginal interest” to Charles, but the variety and quality of what’s on show here is proof that many talented painters, illuminators, sculptors and weavers were at work during his reign in mid-15th century France. One stand-out highlight is the tapestry canopy of Charles VII, used to impress his subjects when he was holding court in public. Another is the collection of illuminated manuscripts and Books of Hours, such as Les Grandes Heures de Rohan, whose prayers and litanies are lavishly illustrated in jewel-like colors with gold leaf highlights.

The Receuil Poétique has an unexpectedly playful element to it. It’s a collection of poems dedicated to the king and it includes a puzzle. Letters scattered among the illustrations can be rearranged to read: “Vive le très puissant Roi de France, Charles le septième.” (“Long live the most powerful King of France, Charles VII.”) And to discover a little of Charles’ story is to understand why those artists loyal to him used their work to pay him tribute and why he himself commissioned pieces to reinforce the legitimacy of his kingship. For his reign began in turbulent circumstances.

In 1418, before he was even officially crowned king, Charles had to flee Paris when the Burgundians staged a coup and there was also the ongoing problem of fighting off the English whose king, Henry V, was laying claim to the French crown. Charles took refuge in Bourges and it was a number of years until – with the support of Joan of Arc – he was crowned at Reims. That was a turning point, but it was more years still until he managed to return to Paris and begin the second, more stable, part of his reign. It’s no wonder then, that he used works of art to proclaim his right to rule.

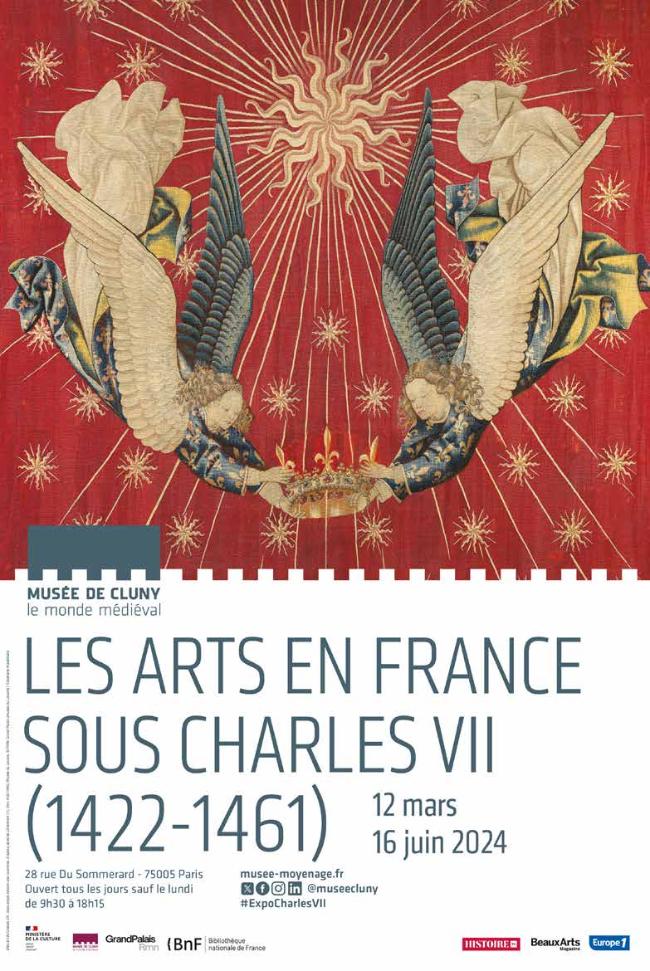

The most striking examples displayed here are two major tapestry works. The Canopy of Charles VII is the only known medieval canopy still in existence. This large piece would have been hung as a vertical backdrop when Charles appeared in public, perhaps to dispense justice or to collect taxes. Its very size is impressive, as is the colorful design showing two angels descending to crown him, thus conveying the idea that he had a divine right to rule.

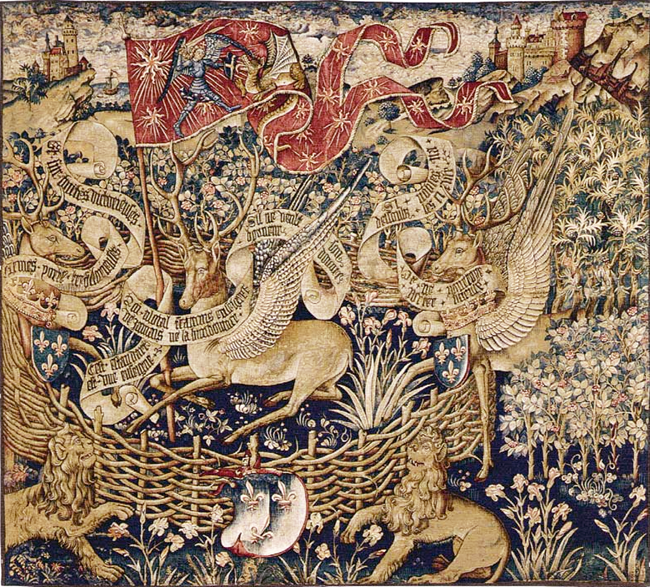

A second large work is the Winged Deer Tapestry which has been borrowed for the exhibition from the Musée des Antiquités in Rouen. The winged deer was Charles’ favorite personal emblem and this splendid depiction would certainly have conveyed the notion of his majesty to his subjects. The tapestry bears his coat of arms too, further reinforcing the message.

One section explains how, during Charles’ absence from Paris in the first half of his reign, many artists worked in the regions. If the court wasn’t in Paris, then those able to commission new works were not there either and artists preferred to work in areas with royal connections. Exhibits illustrate many examples, including the rose window at Le Mans Cathedral which was surrounded by stained glass portraits of Charles and his queen, Marie of Anjou. It was at the court of René d’Anjou that the Hours of Rohan book referred to above was produced. Also exhibited are beautiful little colored statues found in a church near Bourges, the place to which Charles initially fled when he left Paris.

Statue from a church near Bourges. Photo: Marian Jones

Key artists from the period featured here include Barthélemy d’Eyck who left the Netherlands to be a court artist for René, Duke of Anjou. The Book of Hours Eyck created for his patron is here, a prayer book with such beautiful illustrations as his depiction of Mary in a variety of vibrant blues. Also on show is his Livre des Tournois, commissioned to explain the rules governing tournaments, whose lively illustrations are a contrast to the religious works we are most used to associating with the period.

One of the stars of the show is a triptych thought to be by the painter André d’Ypres, who was born in northern France and trained in Flanders. Its three parts are now owned by different museums, but they have been brought together for this exhibition. They are: The Kiss of Judas and the Arrest of Christ (from the Louvre), the Crucifixion (usually at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles) and the Resurrection (from the Musée Fabre in Montpellier). The left-hand panel, portraying the scene where Judas betrays Jesus, was unusual for its time, being one of the earliest attempts to paint a night-time scene.

The best-known French painter of the period was Jean Fouquet, whose portrait of Charles VII has a prominent place here. It was painted in oil on wood in the 1450s just as the king was reestablished in Paris and beginning the second, more stable part of his reign. It is a “no-frills” depiction, without royal emblems, of a man who has earned the right to be king. It pays homage to Charles’ success in stabilizing his realm with the wording painted around the top of the frame, which reads: Le très victorieux Roi de France, the most victorious King of France. Fouquet was a versatile artist who also painted on enamel and glass and designed tapestries. His miniatures for the Book of Hours belonging to Étienne Chevalier – one of which is here – are some of the most exquisitely beautiful little paintings you will ever see.

Detail of a portrait of Charles VII at the Cluny Museum exhibit. Photo credit: Marian Jones

An over-arching theme of the exhibition is the fact that Charles’ reign can now be seen as a turning point in French art, sitting between the gothic period and the renaissance. Political instability led artists to travel around in search of patrons, meaning that ideas were spread and exchanged. A major outside influence came from the Flemish painters who were active in the powerful Burgundian court. From them, French artists took on ideas such as painting in oil on wood and placing a greater emphasis on realism, both of which can be seen in Fouquet’s portrait of Charles. There were exciting new ideas coming from Italy too. Fouquet, for example, had spent time in Rome and must have been inspired by the new ideas taking root there in the earliest days of the renaissance.

Exhibit at the Cluny Museum. Photo: Marian Jones

It’s quite something to have so many top-quality examples of medieval art brought together, especially in such a variety of media. Anyone who is drawn to this period should certainly try to see this exhibition and while you’re there you can explore the museum’s permanent collection at no extra cost. That includes an outstanding piece from just a few decades after Charles’ reign, namely the six tapestries which make up the Lady and the Unicorn series, woven around 1500. Their colorful depictions of the mysterious lady, attended by a lion and a unicorn, seemingly acting out the five senses, then posing a riddle in the last piece, are the museum’s biggest draw.

Musée de Cluny – musée national du Moyen Âge © Alexis Paoli, OPPIC

There are other places in Paris where you can enjoy 15th century art and culture. The collection at the Bibliothèque Nationale includes many superb books and manuscripts from the period, some of which were borrowed for this exhibition! And the Tour Jean-sans-Peur in the 2nd arrondissement was completed in the first decade of the 15th century, when Charles VII was a child and is now a museum. There, you can explore the tower itself, see the bedchambers and other rooms which are furnished in period style and learn about the furniture, clothing, daily life and battle experiences of Charles’ subjects and their descendants.

A mon seul désir, The Lady and the Unicorn – Musée de Cluny Paris, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons

We tend to think the 15th century is too far back to see clearly. But when, thanks to exhibitions like this one at the Musée de Cluny, there’s a chance to reach back into it and admire the art that was being produced, what wonderful treasures there are to be found.

DETAILS

Arts in France during the time of Charles VII

Musée de Cluny

Nearest métro station: Cluny la Sorbonne

Until June 16th, 2024

Hours: 9:30 am – 6:15 pm every day but Monday

Entry 12€

Concessions 10€

Free to under 18s and EU citizens 18-25

Affiche© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle

Lead photo credit : Cluny Museum exhibit. © Marian Jones

More in Cluny, history, Museum