Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation: Stone Walls, Black Iron and the Seine

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Consider the current state of the world.Anti Semitism and antipathy towards Muslims, immigrants, refugees and others have become more blatant both on the streets and in the halls of government. Violence against minorities is growing. In recent news, we read of the herding of gay men into a concentration camp in Chechnya, the killing of the first female Muslim judge in the U.S., and young toughs pulling hijabs off Muslim women.

It is important to reflect on where such hatred can lead when unchecked. Memorials dedicated to the Holocaust have been built all over the world to encourage such reflection – and one of the most unusual and moving of such memorials– the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation— sits along a piece of the Seine just behind Notre Dame in Paris.

The Holocaust was real and it was horrible, but we would all like to just think of it as ancient history. No one really wants to be reminded of barbed wire, gaunt faces, and the spiraling smoke of burning bodies emanating from Hitler’s death camps.

However, as Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel pointed out so often, the only way that we can both honor the dead and make sure such an atrocity can never happen again is to not forget that ordinary citizens in what was considered a modern and civilized society somehow looked the other way or collaborated while incremental steps were taken against their neighbors. Millions of Jews and other minorities were first deprived of their rights by laws denying to them such things as the right to hold certain jobs. In successive steps, they were then forced to live in only prescribed areas; became accustomed to verbal and physical violence without remedy; had their properties confiscated and their businesses destroyed; and, finally, were rounded up and deported to be interned in camps and put to death for no other reason than that they were not Aryans and therefore not entitled to live.

In Vichy France, 200,000 people were deported to concentration camps.

The Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation is dedicated to those 200,000 souls.

“For the dead and the living…… We must bear witness.” “To forget a holocaust is to kill twice.” “Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.” — Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor

What a society permits can start with small things and grow almost unnoticed.

“Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous. More dangerous are the common men, the functionaries ready to believe and to act without asking questions.” — Primo Levi, Holocaust survivor

Hence, the memorials have been built to permit us to visit and mourn – and also to remember and learn. One such memorial is the Shoah Museum in Paris which houses extensive exhibits, both permanent and temporary.

Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation, entering the dimly lit crypt. Photo: Michele Kurlander

Although the Mémorial de la Déportation is a lesser known Paris Memorial, I believe it is more effective than others in its emotional content and in providing the opportunity to simply stop and quietly reflect in an atmosphere of stone and water and iron.

This striking stone edifice, inaugurated by Charles de Gaulle in 1962, is a small building in the shape of a ship’s prow sitting primarily below street level along the Seine and accessed by climbing down a narrow stone staircase onto a stone square surrounded by high walls – an area that is bare except for the walls surrounding it, a narrow entrance into the interior rooms, and a metal portcullis through which you can see a smidge of the flowing waters of the Seine.

I had passed by this Memorial numerous times over the years before I discovered its existence by reading about it in Thirza Vallois’ Around and About Paris (volume 1). It is a bit easier to find now because a small entrance structure and a metal wall were constructed at street level over the last couple of years, for security purposes.

The stated intention of the Memorial’s architect was to create a feeling of claustrophobia and, according to the audiotape guide available for rental at the street level entrance, the configuration of the descent via that narrow stairway is to carry you down to where the urban landscape progressively disappears and noises fade away so that you are forced to feel a kind of isolation and momentary imprisonment, a loss of the sense of time with only air and water and stone surrounding you.

According to author Thirza Vallois, the spear-like motifs of the portcullis at the river side of the courtyard are shaped out of black iron to evoke the memory of those whose flesh was lacerated by the Nazi torturers.

Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation. Photo: Michele Kurlander

Gazing at just a bit of the Seine through those bars, you do shudder for a moment. But you also feel, along with the sense of isolation, a concurrent sense of harmony, simplicity, and silence, permitting you to reflect and quiet your busy brain.

Thirza Vallois describes the interior as follows: “Respectfully austere, the bare, raw stone walls honour the bare, raw wounds inflicted upon the victims. There is no superfluous pathos in this place, just a few lines engraved on the stone walls”.

Entering the dimly lit crypt through a very narrow doorway opposite the portcullis, you enter a hexagonal rotunda containing the tomb of an unknown deportee killed at the Neustadt camp – on which sits a ‘flame of eternal hope.” Just opposite the entrance is a window through which you view a long narrow gallery lit by 200,000 glass crystals set in the walls (one for each deportee), at the far end of which there sits a single bright light.

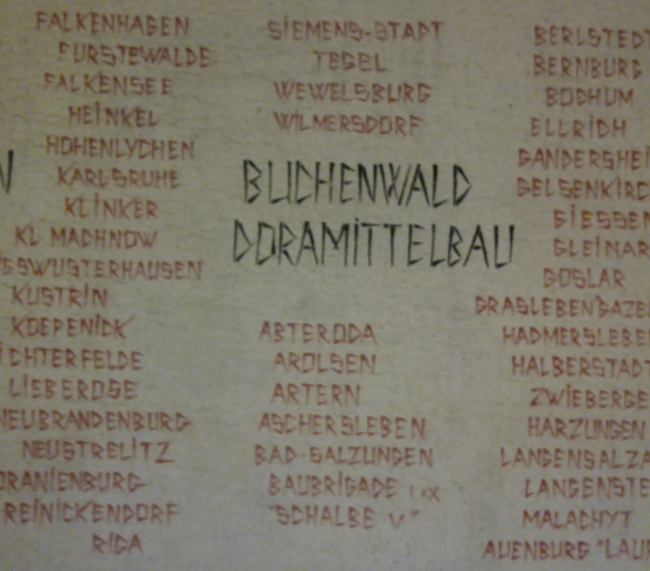

Small rooms on either side of the main room depict prison cells, and in the walls there are triangular urns labeled with the names of the death camps, in which are housed the ashes of some of the dead.

On the walls of all of these rooms, the engraved lines of which Thirza Vallois spoke above include excerpts of works by poet Louis Aragon, poet and resistence member Robert Desnos who died in Theresienstadt (now Terezín in the Czech Republic); Paul Éluard, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation. Photo: Michele Kurlander

A second level has been added to the memorial since my last visit, accessed by a small staircase in the far corner of the room to the left of the entrance. On that level, three rooms have been added. One room is surrounded by stone walls on which the names of all of the camps have been engraved – the more prominent ones in large black letters, and the many others in small letters of red. Also engraved into the walls are maps of the camp locations, and some informational documents are available.

The second room on this upper level is long and narrow and lined on both sides with alcoves- each containing a window in which is set a photograph of an element of the Holocaust experience, beginning with the transport to the camps. Under each photograph is an explanation in both French and English. The room is hardly lit at all except for the window area of each alcove, creating an eerie feeling as you walk- as if you are picking your way along a dark path. A particularly disturbing photo here is that of a dead prisoner hanging from the barbed wire – the title of this one being “Les Exécutions”.

After this room, there is a small one that contains a small screen with a video, after which you can descend via a second narrow stone staircase back to the main level.

As you exit back into the courtyard to return to the world, just before emerging with blinking eyes back into the light of the day, you can see above the doorway the following engraving:

“Pardonne, n’oublie pas.”

This Memorial was designed by French modernist architect Georges-Henri Pingusson.

Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation, Square de l’Ile-de-France, 7 Quai de l’Archevêché, 4th arrondissement. Tel: +33 (0)1-46-33-87-56. Open every day except Monday; From October 1 to March 31, 10am – 5pm; April 1-September 30, 10 am – 7pm. Generally open the last Sunday in April for a ceremony.

Lead photo credit : Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation. Photo: James Evans/ Flickr

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY