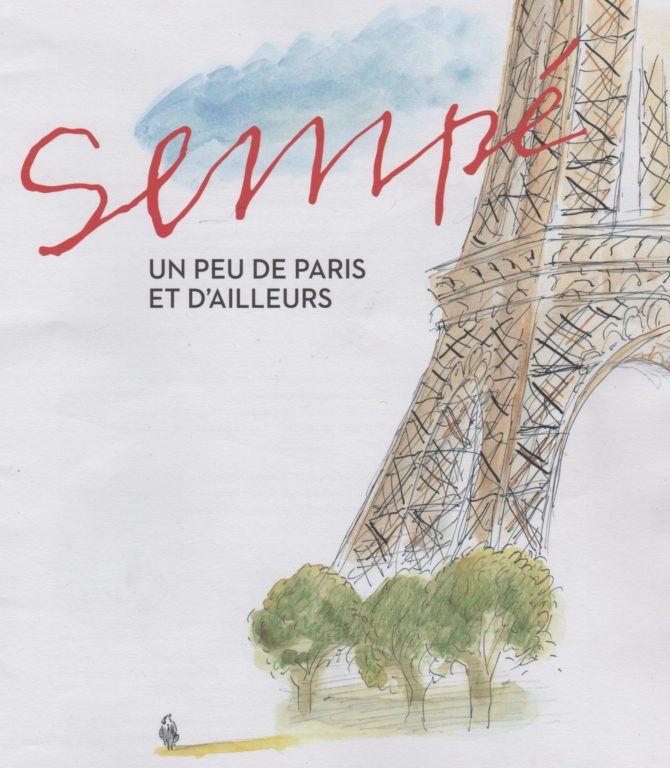

Sempé, the Celebrated Cartoonist, and His Love for Paris

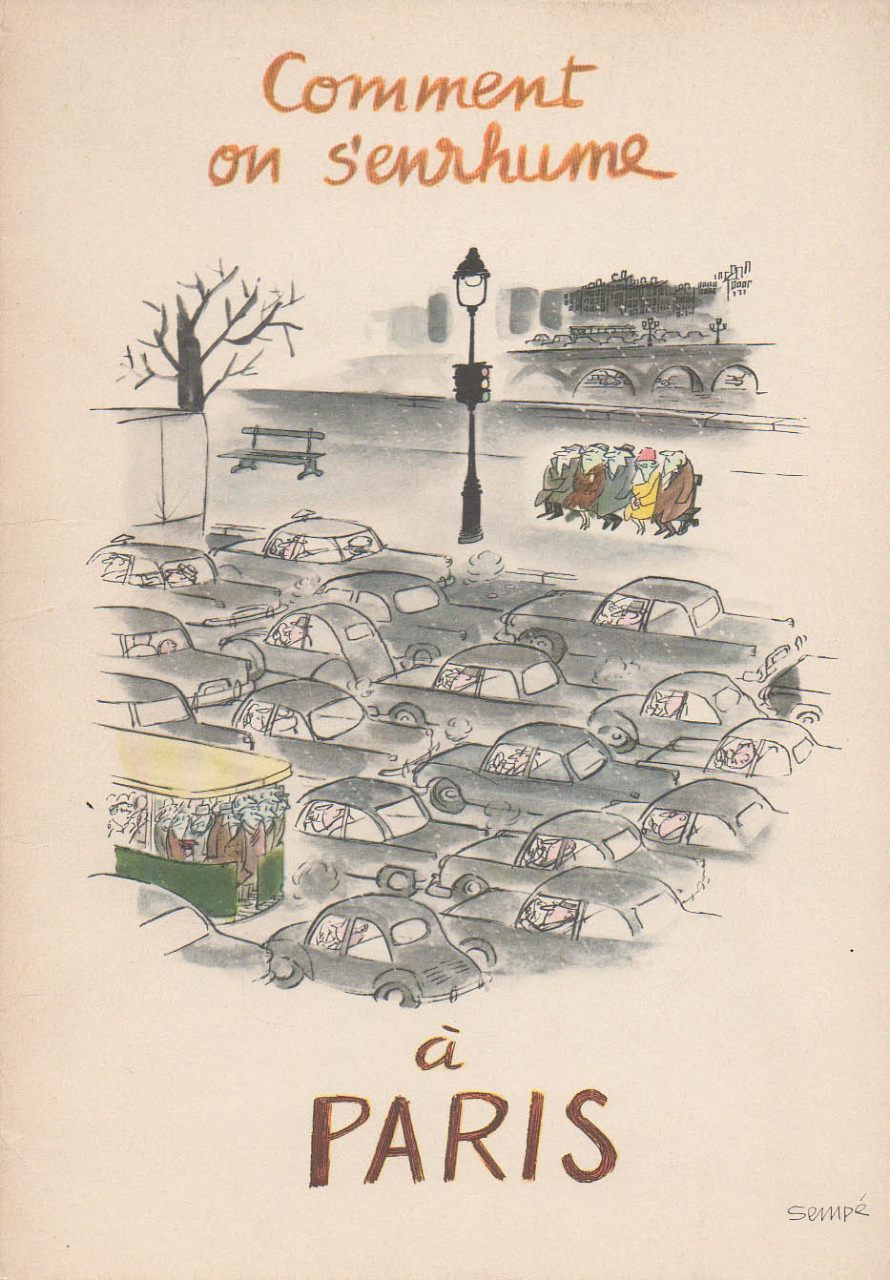

The illustrator Sempé was born Jean-Jacques Sempé in the small village of Pessac, in the Gironde départment near Bordeaux, in 1932. Sempé’s work is instantly recognizable. He is known internationally for his whimsical illustrations of countrysides and cityscapes. His watercolor and pen & ink drawings are typically drawn from either a distant or high viewpoint and are often set in a Paris of mansard roofs, French windows, wrought-iron balconies,and Deux Chevaux cars, painterly impressions of a Jacques Tati wonderland. Dwarfed by their surroundings, his figures are generally small men, sometimes balding, stick thin or plump, with big noses and neat little mustaches in the company of small wives, equally thin or plump, who usually match their spouses’ foolishly defeated yet hopeful demeanor. His humor ranges from mildly ironic to riotous, but his love of Paris and Parisians is unmistakable.

Jean-Jacques Sempé at the Salon du Livre in Paris 2011. Photo: Thesupermat /Wikipedia

Sempé was a late bloomer. He was expelled from school as a young man and subsequently failed to pass exams for employment at the local post office, bank or railroad. He finally found work as a door-to-door salesman, selling tooth powder and delivering wine by bicycle in the Gironde. Bicycling soon became the joy of his life and later on a motif in his drawings. Many years later he said, “For thirty years, I went around everywhere on my bicycle. No matter the destination, rain or shine, I’d go there on my bike. Even if I was going to a fancy event, I’d show up in my tux in ankle straps, rain-drenched but happy.”

Sempé exemplifies the saying, “Do what you love, love what you do.” In 1950, after lying about his age, he joined the army. It was the only place that would give him a job, a meal, and a bed. He would occasionally get into trouble for drawing during guard duty while he was supposed to be keeping watch.

After being discharged from the army, he followed his heart to Paris and began to draw earnestly everyday, trying to sell his cartoons. In fact, there wasn’t a day that went by when he didn’t draw something and try to sell what he’d created to newspapers. He won his first award in 1952, which was given to encourage young, amateur artists to turn professional.

“Le petit Nicolas prend l’avion” by Sempé

It was while working within the cartoon industry that he first met René Goscinny– who is remembered for the wildly popular Astérix comic books. In 1954 Goscinny suggested to Sempé that they collaborate on a series of books called Le Petit Nicolas, to be written by Goscinny and illustrated by Sempé. The first of these was published in 1959. The books depict an idealized version of childhood in 1950s France. Sempé illustrated Le Petit Nicolas based on his own childhood memories. It was unusual at the time for children’s literature, even comics, to depict experiences of the child rather than an adult interpretation of a child’s world, and he slowly gained attention and a following.

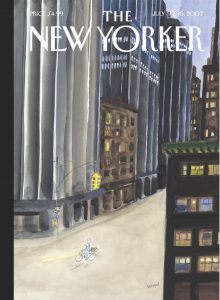

Sempé’s “Fresh Produce” illustration for the cover of The New Yorker

Though Goscinny’s encouragement was significant, nothing was more influential than the cartoons of Charles Addams, Saul Steinberg, and James Thurber, which Sempé first discovered in discarded copies of The New Yorker magazine. He was so moved and overwhelmed by their work, that he swore he’d never look at another New Yorker until they hired him. In the late 1970’s Sempé followed his dream and traveled to New York. Soon, his illustrations began to appear on the covers of The New Yorker, 166 to date.

Some of his more recent cartoons have timely, universal references, while others are quintessentially French. There are a few involving cellphones, and one reflects the doping scandals that plagued the Tour de France, depicting a little old lady shooting up before pedaling her bike up a steep country road.

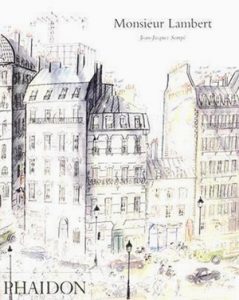

“Monsieur Lambert” by Jean-Jacques Sempé

Monsieur Lambert, written in 1965, is a graphic novel set entirely at a small bistro called Chez Picard, where the same men gather every day to dream and lie about the three predominant French themes – sex, politics, and football (soccer). Recently, I found four small paperback volumes of his collected cartoons at a vide-grenier (flea market), the titles of which speak for themselves: Nothing Is Simple, Everything Is Complicated, Sunny Spells, and Mixed Messages. In 2014, Phaidon Press– normally a publisher of high-end art books– released the largest collection of Sempé’s work in English for the first time; it is a remarkable collection.

Sempé will be 84 this August. He no longer gets around on a bike, but finds adventure in simply getting in and out of a car and watching people on the streets from his apartment on the Left Bank in Paris.

“Comment on s’enrhume à Paris” by Jean-Jacques Sempé

REPLY