Théodore Vacquer: Archeology in Paris, Old and New

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Parisians live their everyday lives surrounded by history, but they live on top of it too. Remnants of long-gone civilizations lay just beneath their feet. City planners have long been content to keep these artifacts buried beneath the pavements of Paris. From 1853 to 1870 Paris was refashioned into a modern city, and that, said Baron Haussmann, was that. It’s only been in the last-half century that these treasures have been seen as important. Today there are ongoing archaeological excavations of note.

In 2023, archaeologists uncovered 50 graves in an ancient necropolis – a “city of the dead” – just meters from the Port Royal RER on the Avenue de l’Observatoire. Dating from 2,000 years ago, this cemetery was unearthed during the construction of a new exit to the Port Royal station. This surprising discovery – just three meters beneath the well-walked pavement – offers a rare look into the Roman outpost which existed here before Paris: Lutetia.

Referred to as the Saint-Jacques necropolis, Lutetia’s largest burial site was partially excavated in the 1800s. Only artifacts considered valuable were removed; skeletons and funereal offerings were reburied with the rest of the site. Today’s archaeologists have uncovered a new section of the same graveyard. Safe to say these 21st-century scientists have a full appreciation of what they have.

The Saint-Jacques necropolis archeological site. © Camille Colonna / INRAP

Although the dead were interred in wooden coffins, the only remaining evidence of the caskets are their metal nails. Some of the bodies were buried with offerings, such as jugs and goblets, and archaeologists have also found personal effects like jewellery, hairpins, belts and shoes alongside their bones. Archeologists from the Institute Nationale de Recherches Archeologiques Preventatives, (INRAP) were able to date the burial site to the 2nd-century CE, due to a coin found in one of the skeleton’s mouths. The coin was a bribe to the ferryman of the underworld.

INRAP says the necropolis may spread further across the south of Paris. However, its secrets will remain buried – archeologists are consulted only when new construction threatens to damage historic sites.

A bronze key from Gallo-Roman Lutetia, displayed at the Carnavalet museum. Photo: Pierre-Yves Beaudouin / Wikimedia commons

Five kilometers to the south of Port Royal, in Ivry-sur-Seine, a group of INRAP archeologists have been analyzing the beginnings of Paris urbanization. Found in the form of a village dating back to 4,200 BCE, these remains dating from the middle Stone-age to the early Bronze-age, were uncovered during the building of a monumental urban project, the Ivry Confluences. The rich and densely packed dig-site, found off one of the spokes of the Place Gambetta, contains the remains of four houses from the Early Bronze age and over 1,200 artifacts. The INRAP team had just six months to examine the site before handing it back to developers.

Excavation of the Bronze Age houses in Ivry-sur-Seine. Photo: © Denis Gliksman, Inrap

In the early 1800s, the discoveries of pagan tombs became more prevalent as Paris developed. Experienced archaeologists from Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition came to realize that their hometown was built over the traces of Roman streets. Scholars began to take note; every new discovery forced them to re-examine what lay just beneath the Paris map.

Then came the great urban reconstruction program of Baron Haussmann and his back-pedaling foil, Théodore Vacquer. As Haussmann created a new city out of the murky, winding Paris streets, many archeological relics were exposed. Haussmann had no interest in the Paris of antiquity, but in the rubble Vacquer discovered the lost city of Lutetia.

The Gallo-Roman thermal baths inside the Cluny museum. Photo: Céline Rabaud / Wikimedia commons

As a very young architect, Théodore Vacquer (1824-1899) watched the chance discovery of 6th-century tombs at the abbey of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois. This developed in Vacquer a strong appetite for the history of Paris and he began to travel around the city’s construction sites cataloguing what had been exhumed in his abundant countless notes. His devotion and his methods of observation caught the attention of the Parisian administration.

“I soon realized that the diggers’ pickaxes were destroying ancient remains on a daily basis in all neighborhoods. I then formed the project of carefully monitoring all the excavations that were being carried out in Paris.” T. Vacquer.

Théodore Vacquer was a quiet, peculiar man, rumored to be as tense as a tightly wound hedgehog. In 1866, Vacquer was commissioned by the Parisian administration to monitor all of Haussmann’s building sites and draw up an inventory of archaeological remains. His research brought to light the Roman origins of Paris, while Haussmann tried to cover it up again.

Portrait of Théodore Vacquer. Unknown author. Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris. Public domain.

As the demolition progressed, Vacquer identified the medieval ramparts on the Île de la Cité, the Roman street plan, a theater on the Rue Racine, and a forum complex on the Rue Soufflot, to name only a few. His discoveries were numerous. He was responsible for the partial excavation of the baths at the Cluny museum site, once erroneously thought to be an imperial palace. He investigated cemeteries to the southeast of the Luxembourg gardens which extended along Boulevard Arago towards the Gobelins neighborhood. Vacquer presided over the first excavations of the Saint-Jacques necropolis, where Boulevard Saint-Jacques and rue Pierre-Nicole meet – part of the necropolis which the modern-day archaeologists are researching now. It’s easy to see why Paris’s fifth arrondissement is called the Latin Quarter!

A sarcophagus found during excavations on the rue de la Montagne-Sainte-Geneviève. Photo: Emonts ou Emonds, Pierre. Between 1862 and 1905. Carnavalet Museum.

The most accessible of Vacquer’s findings was the Arènes de Lutèce. These ruins were found in 1869 during the construction of one of Baron Haussmann’s new streets – rue Monge. Built in the 1st century, this arena is one of France’s largest examples of a Roman amphitheater. Its 15,000 spectators – double the population of Paris/Lutetia at the time – would have witnessed gladiatorial battles, animal fights and aquatic events. When the Romans retreated from Gaul, 4th-century Christians took over the area for their own burial ground. A 12th-century English eyewitness spoke of a great circus full of immense ruins. Those ruins would have been further decimated by the building of the city wall in 1190-1215. Its medieval name “Clos de Arènes” was forgotten, and the site became overgrown.

Haussmann, like most municipal officials, largely ignored the astonishing Gallo-Roman theater that Vacquer wanted to save. Judged not grand enough to be worthy of preservation, it contributed nothing to the myth of modernity that Haussmann was busy constructing. Haussmann designated the area for an omnibus terminal. However, demolition dragged and the site was spared.

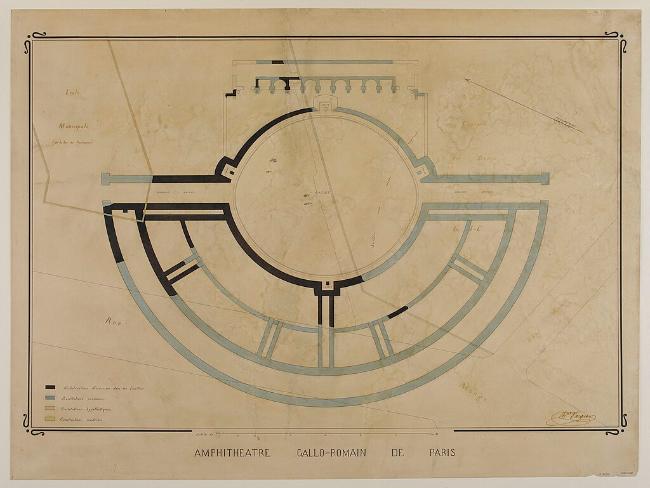

Restitution of the arènes de Lutèce by Théodore Vacquer (drawing, 1871). Wikipedia commons

In the 1880s when more of the rue Monge location was unearthed, Vacquer was too disenchanted to care about its preservation. Fellow archaeologists, and amateur conservation enthusiasts including Victor Hugo, took the reins. “It is not possible,” Hugo proclaimed in an open letter to the administration, “that Paris, the city of the future, should renounce the living proof that it was a city of the past. The arena is an ancient mark of a great city…The municipal council which destroys it would in some manner destroy itself.” These words from the venerable poet had effect.

Conservation was instantly decreed, but the restoration work of the arena was anything but instant – it was finally finished in 1918. Today the arena hosts Les Nuits des Arènes, an annual treat which includes family-friendly music, theater, and acrobatics. In 2024, the emblematic arena will be one of the locations of Paris fête les Jeux, festivities celebrating the Olympic Games. Mainly the quiet, treed arena is a place to have lunch, or watch a game of pickup football.

Les arènes in 1897. Photo: Clément Maurice. Public domain.

An easy (and free!) way to appreciate the development of Paris’s urban archaeology and to see Vacquer’s contributions to Parisian history, is to visit the Musée Carnavalet, located at 23 rue de Sévigné (3rd arrondissement). In 1872, Théodore Vacquer was appointed as a curator of the new Musée Carnavalet, which was specifically created to showcase the history of Paris. In the basement vault he began to amass a collection of architectural artifacts drawn from Haussmann’s deconstructions, including Roman sculptures and stele, carved pillars, and, before they were lost forever, remarkable architectural elements taken from medieval households.

Vacquer made destruction and reconstruction his life’s work. Only recently has he been recognized for his labors. Although Vacquer published nothing during his lifetime, his copious notes are at the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, 24 rue Pavée (4th arrondissement). In 2022, the city of Paris paid tribute to Théodore Vacquer by giving his name to one of the approaches leading into the Lutèce arena. After so many years diligently working on the sidelines, Vacquer is now seen as one of the great contributors to Parisian history.

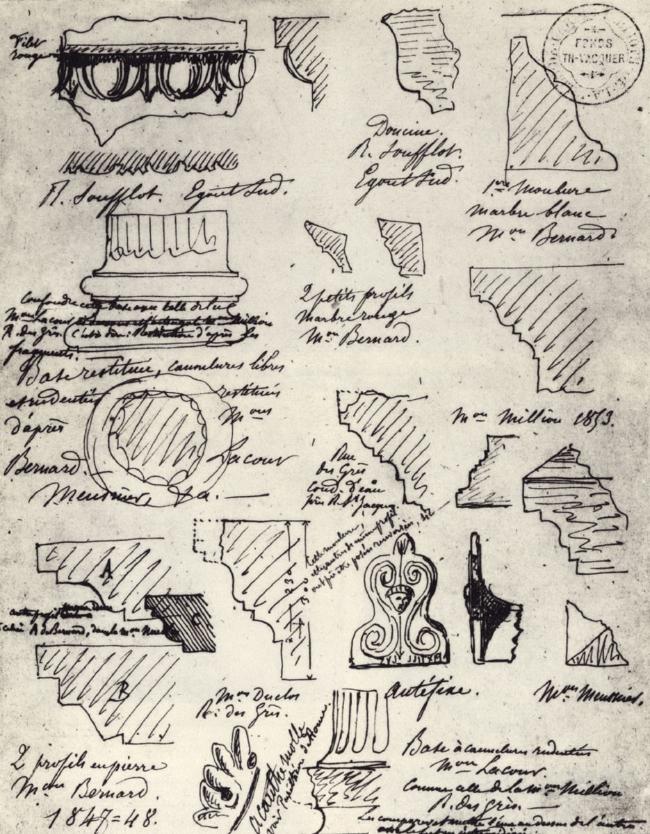

Vacquer’s sketches of artifacts excavated from the forum on rue Sufflot, ca. 1847. Credit: Cabinet magazine

Besides the Arènes de Lutèce and the Musée Carnavalet, Roman Paris can be experienced at the Crypte Archéologique de l’İle de la Cité. Found in the forecourt of Notre Dame, the crypt displays archaeological remains discovered under the cathedral during excavations from 1965 to 1972. It’s a unique view of the urban and architectural development of Paris’s historical heart.

Visible from the corner of the boulevards Saint-Michel and Saint-Germain, the Roman Thermes de Cluny are among the largest ancient remains in northern Europe. These baths are part of the Musée de Cluny, a really amazing tribute to Medieval Paris.

Lead photo credit : The Arènes de Lutèce, Photo Credit: Mbzt/Wikimedia Commons

More in Archaeology, archeology in Paris, Necropolis, Paris history, Vacquer