The Smart Side of Paris: Saint Médard’s Ghosts

Tucked away in the fifth arrondissement, on Rue Mouffetard, just five blocks from the Jardin des Plantes, is an exceptionally nondescript little church: Saint-Médard. It’s such a peaceful place, it’s hard to imagine the hysteria-fueled spectacles that once took place in its cemetery.

Tables from the popular Les 5 bistro crowd the plaza in front of the church, and a small rectangular park fills with children and parents every afternoon. There is a Wallace Fountain behind the church, and a sign in front designating the church as a historical monument dating back to the 12th century, long before the village of Saint-Médard was swallowed up by Paris. As far as I can tell, not many people read the sign.

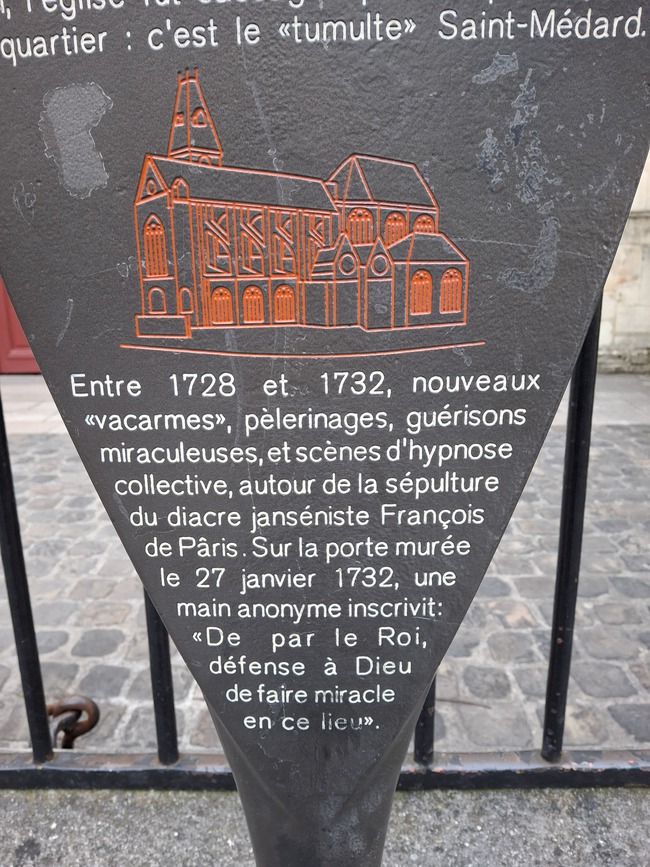

Saint-Médard historical marker. Photo: John Eigenauer

The great philosopher and encyclopedist Denis Diderot lived nearby on Rue Mouffetard. He witnessed firsthand one of the most controversial and improbable religious spectacles of the 18th century right there in the little cemetery next to Saint-Médard, where the park sits today: a spectacular series of miracles. Years later, he couldn’t help writing about them in his inimitably skeptical way: “A certain street [Rue Mouffetard] is full of shouts of joy: there, in a single day, the ashes of a saint once performed more miracles than Jesus Christ did in his whole life. People are running there… I follow the crowd. When I finally arrive, I hear cries of: ‘It’s a miracle! A miracle!’ I approach, I look, and I see a small cripple parading about with three or four charitable people holding him up. So where is your miracle? Don’t you see that this child has only exchanged one set of crutches for another?”

In a city renowned for its devotion to Catholicism, Diderot spoke too freely about his heterodox ideas concerning religion. His landlord’s wife, who took orthodoxy seriously, found Diderot’s loose tongue intolerable and reported him to the local parish priest at Saint-Médard, who investigated.

Église Saint-Médard de Paris. Photo: John Eigenauer

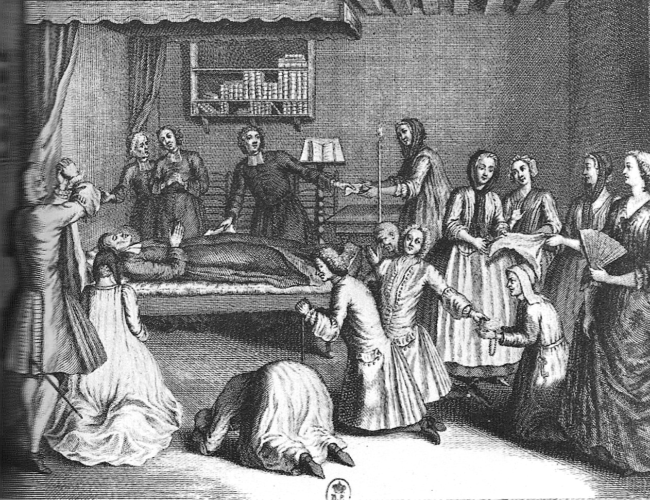

But who was this saint whose ashes performed miracles? People in the neighborhood, who were quite poor, had been deeply touched by the devotion of a local parish priest, François de Pâris. As I wrote in the book Paris and the Birth of Public Knowledge, he “earned the love of everyone he was devoted to for his willingness to do anything to ameliorate their misery, and for his extreme asceticism that included wearing a hair shirt, beating himself until he bled, eating once a day, and never lighting a fire even in the depths of winter. By 1727, he had ruined his health and he died at the age of 37. His self-denial was perceived as holiness, and his holiness deserving of devotion from the masses. After his death, everything from his fingernails to splinters from his coffin became holy relics. Miracles in his name followed his death, centered on his tomb near the church at Saint-Médard.”

Engraving of François de Pâris’s death. Anonymous. 1750. Public domain

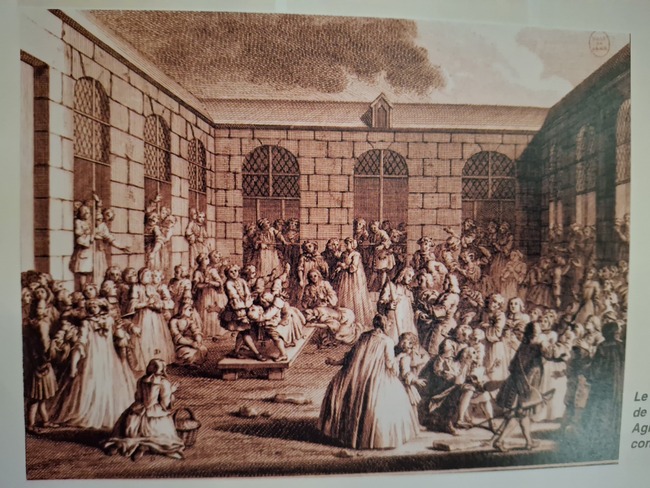

People visiting de Pâris’ grave at Saint-Médard prayed for his intercession to cure their diseases; some reported that they had been cured of every manner of disease ranging from blindness to paralysis. These reports became public, driving curiosity, which eventually turned into spectacle, the graveyard at Saint-Médard becoming a mecca of displays of hysterical religious devotion. At the peak of the enthusiasm in the Fall of 1731, things got out of hand. People “devoted to public expressions of religiosity began to convulse, their bodies thrown into paroxysms of twisting, leaping, contorting, and screaming.” Because of their wild physical displays, participants came to be called “convulsionnaires,” convulsionists.

This contemporary drawing shows a combination of convulsionists (especially in the center of the drawing) and gawking onlookers. It is reproduced from a booklet produced by Église Saint-Médard, available at the church.

This created a circus atmosphere: as more of the convulsionists gathered at the churchyard, more people came to watch. A market economy developed where people could rent chairs to watch the “moaning, yelling, whistling, caterwauling, convulsing,” and macabre dancing. Priests handed out even the tiniest relic from de Pâris: pieces of wool or wood from his bed. Predictably, merchants followed, selling “healing drugs, belts, crosses, bracelets, garters, iron bands, and portraits” of de Pâris. Surrounding cafés filled up and people sang “Here a Miracle, There a Miracle.” (My irreverent side likes to imagine this tune being a precursor to “Old McDonald”).

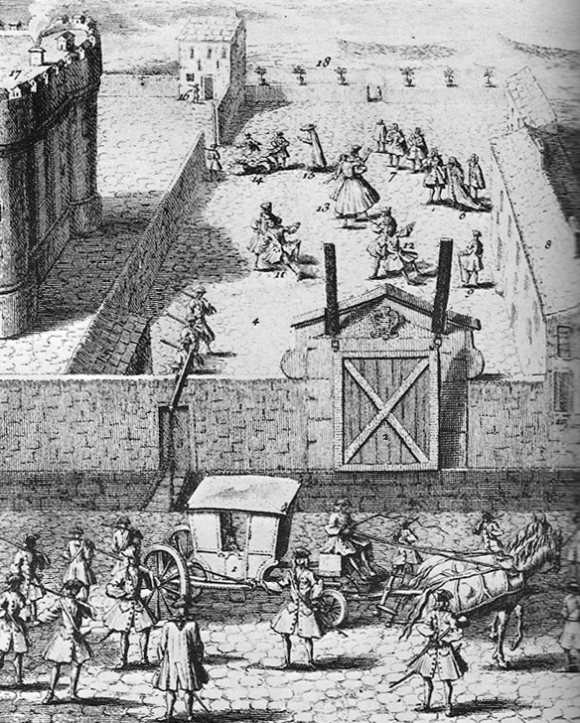

Eventually, the movement got so out of hand that King Louis XV intervened. He issued an ordinance closing the cemetery at Saint-Médard. The police arrived early on the morning of January 29th, 1732, permanently closed the cemetery, put up stronger gates, and posted guards. Later that day, someone posted the subtle and beautifully ironical message on the door of the church that, “By order of the King, in defense of God, it is forbidden to perform miracles in this place.”

Convulsionnaires confined to the Bastille, 18th-century engraving. Public domain

The prohibition only served to drive the convulsionists underground as they continued to meet privately, and their religiosity devolved into bizarre forms of eroticism, sadomasochism, and self-torture. By 1733, the penalty for public displays of convulsions was 500 livres and five years of hard labor. The few intransigent believers apparently grew more hardened: in 1736, the police discovered their plot to murder the king and take over the government.

In 1875, the cemetery was dug up and transformed into a square and a park.

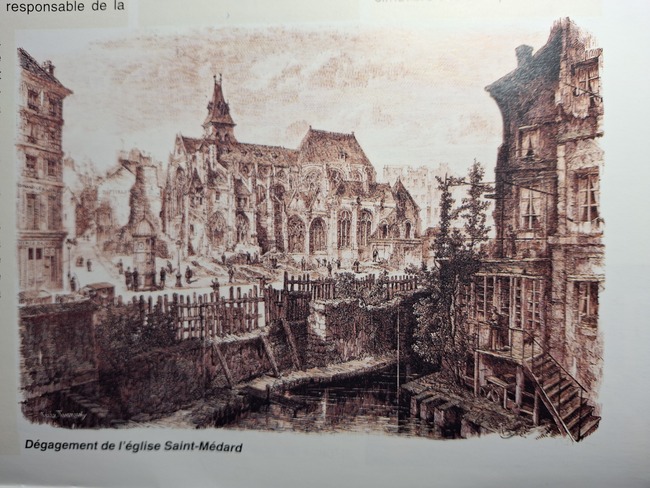

This contemporary drawing depicts the workmen excavating the graveyard. It is reproduced from a booklet produced by Église Saint-Médard, available at the church

And so today, sitting in Les 5 bistro enjoying a glass of wine, or taking your children to play in the little park at the corner or Rue Mouffetard and Rue Censier, you can hardly imagine such a peaceful little spot being at the center of one of the great controversies of Louis XV’s reign.

Louis Braquaval, (1854-1919). “L’église Saint-Médard”. Huile sur bois. Paris, musée Carnavalet.

Lead photo credit : The playground and square Saint-Médard. Photo: Chabe01 / Wikimedia commons

More in Paris churches, Saint Medard, The smart side of Paris