The Shoah Memorial: Remembering the Holocaust through the Unlikely Medium of Comics

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

“Never shall I forget the little faces of the children whose bodies turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky… even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself.” “For the dead and the living. We must bear witness.” “To forget a holocaust is to kill twice.” “Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.” (Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor)

“Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous. More dangerous are the common men, the functionaries ready to believe and to act without asking questions.” (Primo Levi)

“Pardonne, n’oublie pas” (“Forgive, don’t forget”) Carved in the wall above the door as you exit the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation in Paris.

Such atrocities, in retrospect, do not seem possible in a modern society. The citizens of Germany and France were not monsters, were they? Yet somehow, in Germany the Nazis were allowed to move forward in increments – first, isolating Jews from the economy with laws prohibiting non Aryans from being in the Civil Service or practicing law; then prohibiting intermarriage, moving on to boycotts, ghettos, forced emigration, and finally, the rounding up of millions of Jews and other minorities to be killed in concentration camps in what they called the “final solution” and we call the Holocaust. In France, the Vichy government also isolated Jews, required the wearing of the infamous star, and finally rounded up and deported over 200,000 citizens.

Everyone should read “The Journal of Hélène Berr,” the daily diary of a 21-year-old Jewish literature student at the Sorbonne. Hélène wrote about her classes, music, friends and boyfriend, and slowly recognized that something unusual was happening as her daily life was restricted a little at a time. One day, she could no longer ride the Metro past a certain stop; then, she was forced to wear the star, her businessman father was taken away, and finally – her last entry on February 15, 1944 – just 3 weeks before she and her family were arrested – “Horror! Horror! Horror!” She died later that year in Bergen-Belsen. Her diary was sent to her fiancé, who was fighting with the French resistance, and finally published in France in 2008.

The take-away from reading this Journal is that she sounds like you and me. Her daily life is familiar to those of us who grew up in similar circumstances whether in Paris or Chicago, as are her surroundings, until, suddenly, they are not.

Never again, we say, as we wring our hands. We swear to be vigilent and hope that we are caring and sufficiently moral to intercede in time. But how can we be sure that dislike and mistrust by the majority of a society for the minority “others” will not lead again down a slippery slope? The United States interned 2nd generation Japanese citizens during World War II, even while their progeny fought in the army; we are reminded in the recent movie Hidden Numbers of how an African American computer expert in the space program had to run a half mile through the rain to the “colored” bathroom; and now, synagogues and mosques are being vandalized and we are vilifying all those with connections to the Muslim religion or even to countries connected to that religion – to the end that Muhammid Ali’s American-born son was held for hours before being granted entry back into the country simply because of his last name.

To guard against the recurrence of such a horrible affront to humanity, we must not ever forget the details of how it once happened.

“Shoah et Dande dessinée” exhibit at the Memorial de la Shoah in Paris.

To that end, museums and memorials exist to remind the world to never allow even preliminary steps of prejudicial actions against any minority – else yet another society may start down the slippery slope from small unfairnesses to the horrific. It is especially appropriate to visit such memorials in the spring as Holocaust Rememberance Day is April 28 (designated by a 1953 Israeli law).

Paris is the home of a number of such memorials, including a special dedicated section of Père-Lachaise cemetery; plaques with the names of children deported to the camps; a stark and dramatic stone memorial just behind Notre Dame; and, most prominent and importantly, the Memorial de la Shoah in the Marais district.

It was inaugurated by President Chirac on January 27, 2005– the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz– as the Shoah Memorial and Holocaust Center museum. Today it hosts moving temporary exhibits alongside a comprehensive permanent exhibit which includes survivor videos, collected artifacts of the dead, a memorial flame and crypt, original records, a wall of names, and photos of children who died in the camps.

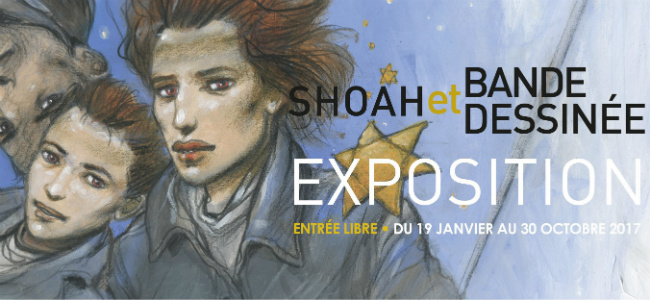

Mickey Mouse in the Gurs Camp by Horst Rosenthal (author), 1942, Mémorial de la Shoah collection. Photo: Michele Kurlander

I found the current temporary exhibit – there until October 30, 2017 – particularly moving because of the juxtaposition of an entertainment medium with the starkly tragic truth. Shoah et bande dessinée (“Shoah and comics”) is an extensive look at how the comic medium has been used to depict, comment, educate (and sometimes even darkly amuse) on the subject of the holocaust through 70 years of different genres and styles.

At the beginning, comics were sometimes produced by the victims themselves. In the first exhibit room, you encounter a small notebook entitled Mickey au Camp de Gurs, in which Horst Rosenthal, interned in the Gurs concentration camp in France in 1942, depicted in 15 pages of colored drawings how Mickey Mouse- in his own mouse words – dealt with life in that camp. You laugh a bit when you see his notation “publié sans l’autorisation de Walt Disney” and the drole and befuddled way in which the familiar Disney rodent deals with the exigencies of being in such a place, confused, for example, when asked for “papers.” Amusing, that is, until you read that Horst Rosenthal shortly thereafter was sent to Auschwitz, from which he never emerged.

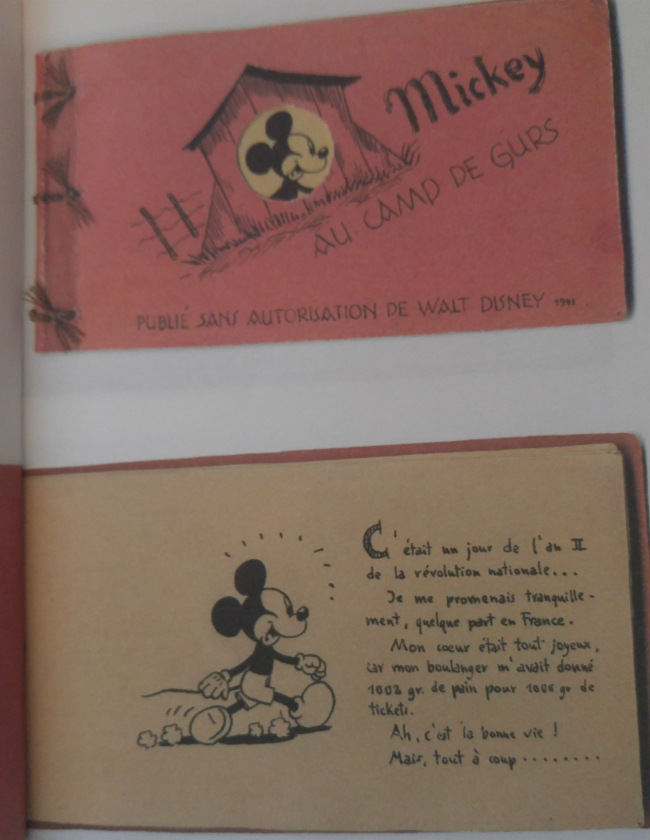

The Plot by Will Eisner

At the end of the exhibition, renowned American cartoonist Will Eisner is also featured. Two of his late-in-life comics address and correct the “two powerful anti-semitic tropes”: the greedy, corrupt Jew (through his “Fagin the Jew”) and the fabricated story about an international Jewish world-conquering cabal – “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion”, a forgery which Hitler not only believed but used as bedside reading. Eisner used his comic works to fight the returning Fagin-like stereotype and to show the “Protocols” for the blatant forgery it was in “The Plot- The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.”

[I purchased the latter Eisner work and recommend it as a really interesting read. Among other things, I learned that (1) The original “Protocols” was published in Russia in 1905 and written by Mathieu Golovinski at the behest of conservatives to use the made up story of a Jewish cabal to discredit Nicholas III’s proposed modernization/liberalization of Russia as a Jewish plot; and (2) Goloveski plagiarized much of the book from the “Dialogue in Hell between Machiavelli and Montesquieu” by Maurice Joly (written in France in 1864 to discredit and castigate Napolean III), switching it around as if this seeming anti-government work had been written by Jews.]

In between these two ends, the various comics are presented chronologically, also to depict the various stages of the world’s recognition of Holocaust facts.

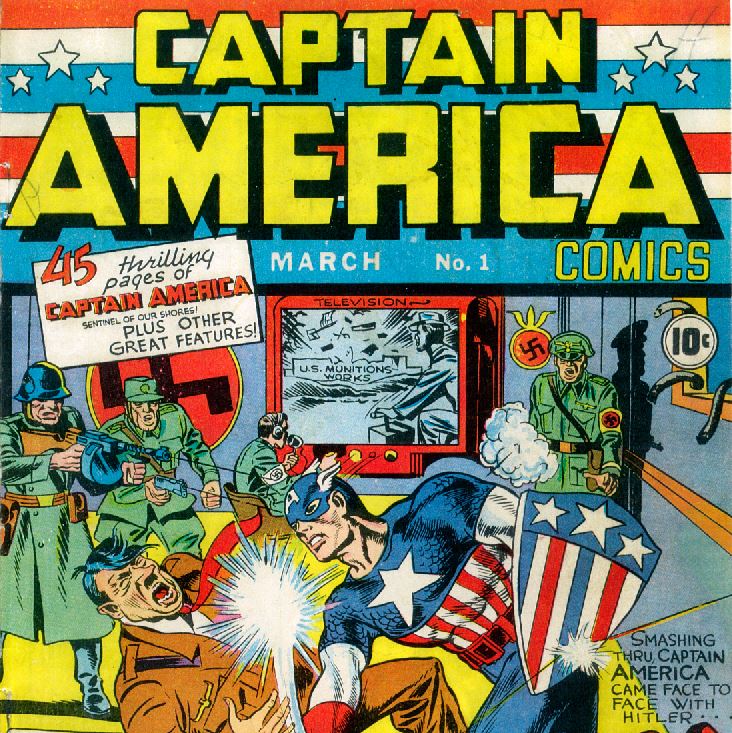

Captain America Comics, Vol. 1 #1, cover by Joe Simon, Jack Kirby, Marvel, March 1941.

I visited the exhibit twice, and still felt the need to purchase the hard cover catalogue to re-read the information.

I was surprised to learn what a “messy and difficult relationship” the world had with the truth of the existence of the Holocaust – finding to my surprise that until at least the late 1970s the Holocaust remained for the most part “taboo in comics and elsewhere.” Superheroes would sometimes end up in the camps but it was never clear that there were Jews there, nor did they try to liberate them. An example is a Captain America comic from 1945 where the cover clearly shows a camp but it is not clear that Jews are the victims…

In a 1945 work called “Dans Un Commando de Mauthausen” published in July of 1945 in the weekly Catholic magazine for young people, Coeurs Vaillants, a priest performs an improvised mass in a death camp, a tortured prisoner is superimposed over an image of Jesus, but nowhere is there any reference to Jews.

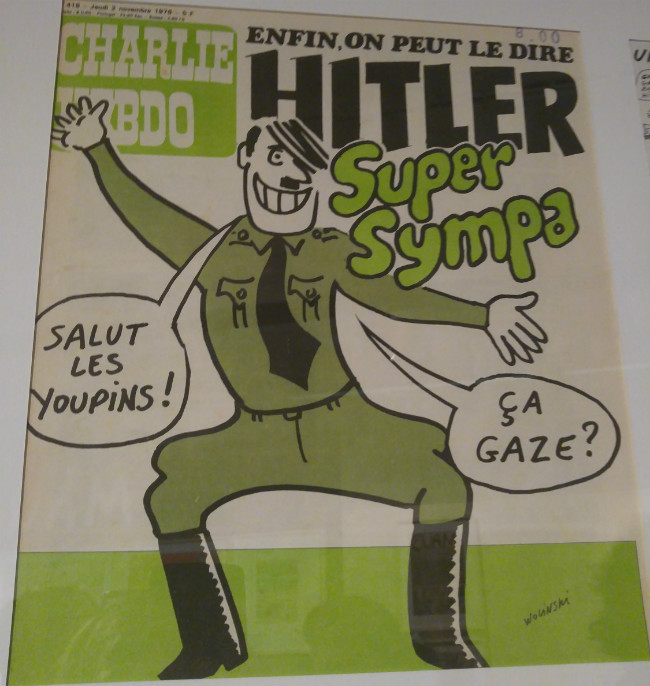

There was what they call a “turning point” in 1978 with the television miniseries The Holocaust, and then such comics as those of Charlie Hebdo brought the facts out of the closet- sometimes appearing, in typical Charlie fashion, to adopt the point of view of the adversary in order to turn against him and at the same time provoke laughter.

In one Charlie cover (number 416 – November 2, 1978) with a story by Georges Wolinski (one of the January 2015 terrorist victims at the satirical newspaper’s offices in Paris), a “Super Sympa” Hitler is laughing and dancing while saying “Salut Les Youpins”– the latter word being a French version of the pejorative for Jews beginning with “k.” At the top are the words “Enfin On Peut Le Dire”. Within the comic an elderly French grandfather tells youngsters “Une Belle Histoire” about how badly he and other French were treated by the horrible Jews until finally whole trains of them were just sent back to their original countries or put in camps to get rid of them – and the children end up yelling “when I grow up I’m going to kill Jews”. Harsh stuff – but it gets the point across unless the reader (not the case one would think with most Hebdo readers) is simplistically literal minded.

Charlie Hebdo cover, photo: Michele Kurlander

Some of the drawings in the depicted works are bare and simple, some so realistic as to be almost photographic. The works range from stark reality to fiction, sometimes substituting animals in place of humans to make the point. Examples of the breadth of the works:

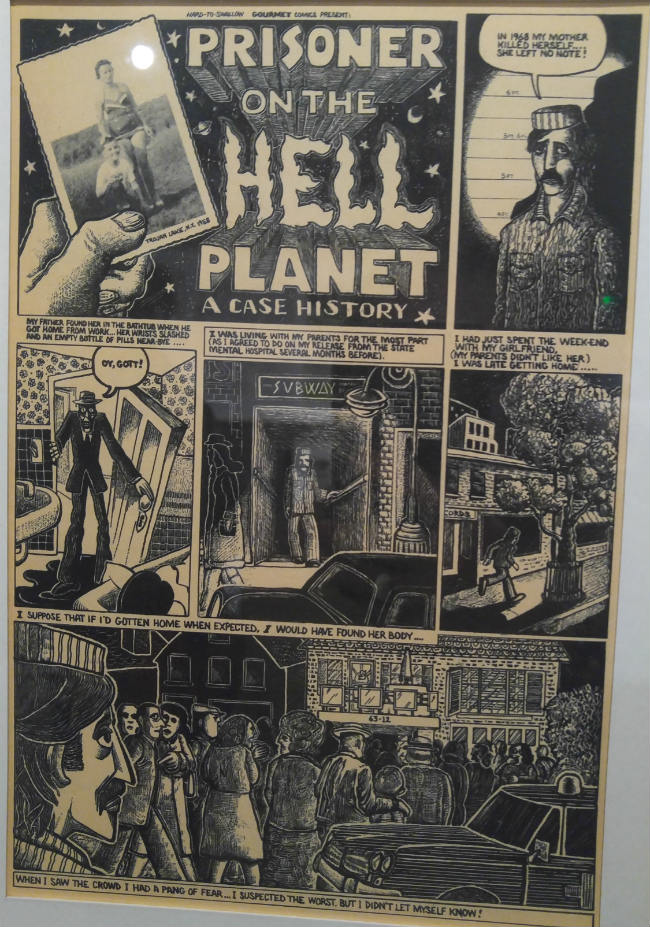

In the 1972 book Prisoner on the Hell Planet, Art Spiegelman uses what is called a “neo-expressionist” style to tell the story of his mother’s suicide in New York many years after she and his father were liberated from the camps. Spiegelman’s renowned graphic novel Maus (serialized from 1980-1991) depicts the protagonists as animals (Jews are mice, Germans are cats, Poles are pigs) and was the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer in 1992.

One of the few examples in the 1950s of a straightforward story about Jews in the camps – published in “Impact #1, 1955”, Bernard Krigstein’s “Master Race” shows in a frighteningly realistic manner the story of a Jew and one of his tormenters in a concentration camp, who then meet by chance in a New York subway. Movie-like camera angles and symbolism such as prison bars and crucifixes add to the impact of this work.

La Bete Est Morte, published in 1944, does depict the Holocaust just after the war – through a world of animals, where the Germans are wolves, the French rabbits, the Belgians lion cubs, the English dogs, the Americans Bison, and the Russians bears- in accurate detail, but leaves the impression that the Jews were rebels and rounded up for that reason, not because of their so-called race. This work is brilliantly colored and looks like a Disney cartoon with real bullets dealing out real death.

In the 2012 “L’Enfant Cachee”, Dounia, a grandmother, tells her grandaughter the story that even her son has not heard before about how she was hidden away for years by neighbors and friends who risked their lives to save her when her parents were taken away to the camps, and how, after a long search, she was able to find her mother at the end of the war, though her father had died. This hardcover comic was written by Loic Dauvillier and drawn by Marc Lizano and Greg Salsedo, and can be found in English under the title “Hidden.”

The story of Irena Sendlerowa, a Polish nurse, humanitarian and social worker in Warsaw, who risked her life to smuggle 2500 Jewish children and provide them with false identity documents and shelter. She was arrested, tortured and sentenced to death but survived the war and was recognized in 1965 by Israel as one of the “Righteous”. She died in 2008 after receiving numerous awards, and recently a three-volume comic series is being published entitled simply “Irena”. You can see – and purchase – the first volume at the Shoah Memorial.

Finally, in the last room of the exhibition, there’s a bin where you can see the originals of many of the works seen on the walls.

Photo: Michele Kurlander

When you visit, leave plenty of time to wander through the rest of the building. The permanent exhibit is on the lowest level, and the Memorial to the Unknown Jewish Martyr is reached by descending a staircase around the corner from the reception area.

This site began with the construction of the building housing the Memorial to the Unknown Jewish Martyr in October, 1956; in 1957, ashes of victims from Auschwitz-Birkenau, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor, Treblinka, Mauthausen and the Warsaw Ghetto were buried in the memorial crypt which also contains a map of the Warsaw Ghetto and a door from that Ghetto; and behind glass in an alcove near the crypt are housed the index cards created by the Vichy government between 1941 and 1944 to identify Jews and aid the French police and the Nazis with roundups. This building still exists, as it was incorporated into the new construction in 2005.

Don’t miss the bookstore which houses France’s largest number of titles on the subject of the Holocaust. It currently contains copies of many of the comic book works featured in the temporary exhibit – in both French and English versions.

I visit the Shoah Memorial every couple of years to see the temporary exhibit and, at the same time, to revisit the photos, artifacts and videos in the permanent collection. This time, I sat at the entrance to watch a video depicting the history of anti-semitism, spent some time seated in front of a video of one of the Shoah victims telling her story, stood at the wall covered with photos of children who did not live through the war, and took a deep breath as I looked again at the personal belongings, letters and photos of those who did not survive to claim them.

Finally, I went back to the comics exhibit to sit around the bin of original comics and leaf through the pages – then descended to the bookstore where I purchased some to read on the plane home.

An emotionally draining but informative and important experience.

Mémorial de la Shoah, 17, rue Geoffroy l’Asnier, 4th arrondissement. Tél : + 33 (0)1 42 77 44 72, [email protected]. Website: www.memorialdelashoah.org/en/. Open every day except Saturday (10 a.m. to 6 p.m.) and until 10 p.m. on Thursday

Lead photo credit : "Shoah et Dande dessinée" exhibit at the Memorial de la Shoah in Paris.

REPLY

REPLY