The Paris Courtesans and Their City Haunts

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The French have arguably more words to describe the oldest profession in the world than any other language. Putain, salope, racoleuse, grue, catin, poule, poufiasse – the list for “prostitute” goes on and on, with more words added every generation. The most innocuous– and probably still the kindest moniker– is la dame de la nuit. In addition, in 19th century France, there were other commonly used names for the different levels of prostitutes, starting with les grisettes. These were the working-class girls who were part-time prostitutes, their poorly paid work forcing them into turning tricks to supplement their income. The name derived from the grey (gris), coarse clothing they wore.

Les lorettes were considered the next step up – women who supported themselves solely by prostitution, or possibly being the kept mistress of just one man.

However, a courtesan, also known as “une grande horizontale,” was none of these, even though she may well have started out her career being called any of the above. (Coco Chanel, for example, who rose from extremely humble beginnings, became une grande horizontale, before her incredible talent, albeit originally financed by a wealthy lover, gave her the independence to choose her own lovers as and when she wished.)

An Officer Making His Bow to a Courtesan 1662 painting by Gerard ter Borch, held at the Museum Polesden Lacey. Photo credit © Polesden Lacey, Wikimedia. Public domain

A courtesan, although still using sex to fund her lifestyle, was much more than a five-minute, hourly or even nightly transaction. Being good in bed, although clearly a prerequisite for being a true courtesan, was only one factor that elevated just a few of these women to the unimaginable wealth, prestige, influence and notoriety that they ended up possessing. The most famous courtesans had several things in common: an innate intelligence and a self-taught education which they applied assiduously in learning everything they could about entertaining, running a house, servants, acquiring the right accent, being at the cutting edge of fashion, and always being interesting, excitingly different.

(The exceptions were high-bred courtesans, who for whatever reason, were no longer protected by families and husbands and, without their own wealth, fell back instead on rich patrons.)

The lower bred courtesans, however, also possessed charm and wit in abundance, and an indefinable allure, a je ne sais quoi, that fascinated men to distraction. Many were beautiful, but not all, although most had wonderful bodies, the palest of skins, the tiniest of waists, the softest of shoulders. These were women who although not strictly accepted in high society, still managed to influence fashion and inspire playwrights, authors and artists, while mixing easily with not only the powerful and titled in the land, but also enchanted even the royal. Their rewards were immense: fine houses, jewelry, clothes, money and, peculiarly, freedom.

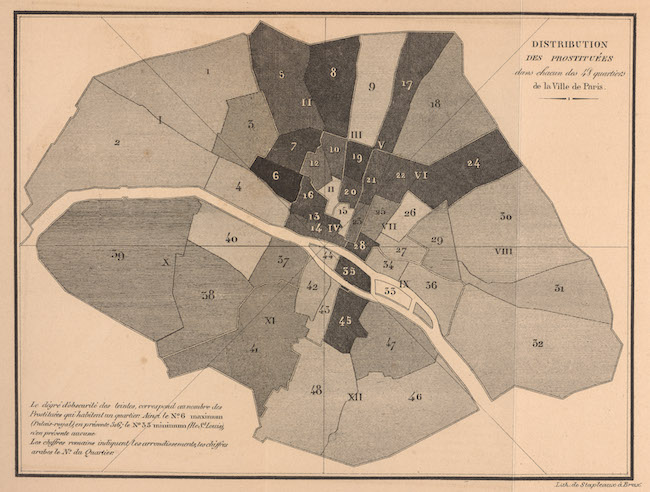

Distribution of Prostitutes in Paris, 1836 – University Library. Photo credit © Alexandre Jean-Baptiste, Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

High-class wives throughout the 18th and 19th century, during the heyday of the courtesans, were not allowed to own their own property, so being married even to the richest man in France simply meant they belonged to him. They were effectively his chattel. High-class women did not work, and in fact were mainly educated only up to the point of making them good wife material. Consequently, their prospects, their raison d’etre, depended on an arranged marriage to someone of at least an equivalent status.

A courtesan, on the other hand, unencumbered by marriage and the inheritance laws it entailed, remained free to hold on to any property she was given, any gifts of cash, jewelry whatever, and importantly, she was free to choose her own “patrons” as her circumstances dictated. Some courtesans remained for long stretches of time with just one patron, others had several at the same time and some would agree to just one night, but the price would be astronomical for that favor. Many of these courtesans were household names; their fame and fashion preceded them. It was not only men who found them fascinating and irresistible. Writers, artists, and musicians were inspired by them, high class women shamelessly copied their attire, and the general public could not get enough of their exploits.

Courtesans were hardly exclusive to France, of course. In fact the French word, courtisane, derived from the Italian, cortigiani, where during the 16th century, it was applied to well educated, usually talented, women in either song or dance, who attended the court and were “adopted” by powerful rich courtiers. These cortigianes, as with latter-day successful French courtesans, not only possessed the requisite physical attributes, but also intelligence and wit and the ability to engage in stimulating conversation and be a worthy companion both inside and outside of the bedroom. (The hypocrisy concerning “common prostitutes” and cortigianes, was never more extreme than in Renaissance Italy where prostitutes were defiled and treated with brutality, while in the Papal court of Rome, cortigianes were hired for the pleasure of the Popes themselves. Alexander VI, elected Pope in 1492, when he was 61 years old, not content with his six children by his mistress Vanozza del Catenei, fell for the charms of 17-year-old Giulia Farnese who subsequently joined him in the Vatican. She was later, and doubtless without irony, to be the model for Raphael’s fresco of Madonna.)

From the 5th century BC, courtesans in China, Japan, India, Arabia, Italy and Europe flourished, but it is hardly surprising that in 18th- and 19th-century France, it was Paris which attracted the most famous of them.

Watercolour of Marie Duplessis at the theatre. Photo credit © Camille Roqueplan, Wikipedia. Public domain

Here is the story of just two of these fascinating courtesans.

Marie Duplessis (Alphonsine Plessis), Lady of the Camellias, (La Dame aux camélias), 1824-1847

The life of Marie Duplessis demonstrates the seemingly impossible and insurmountable rise of a poor girl from the country to one of the greatest courtesans of the 19th century.

And all in a scant seven years.

Born in Nonant-le-Pin in Normandy, Marie was reputedly sold to an old man at the tender age of 14. It’s hardly surprising, then, that a year later Marie moved to Paris to work as a seamstress. (Wages for seamstresses in Paris, as for milliners in London in the 19th century, were so low as to be impossible to live on, and prostitution in these professions was more than commonplace.)

Marie had the advantage of exceptional good looks; she was petite, fair skinned and dark haired, and had to all accounts an enchanting smile. She was also intelligent, ambitious and acutely aware of where her good looks and the patronage of powerful men could take her.

The Duc de Guiche discovered Marie when she was 16 years old. He proved a more than willing instructor of Marie, coaching her in the intricate mores of a courtesan. He had found a superb and willing pupil. Marie already had great sense of fashion and a natural elegance, and these attributes combined with her insatiable quest to educate herself. Her wit, ambition and sympathetic character propelled her to the courts of Paris in just about the same amount of time it took for her to lose her Normandy accent and acquire a Parisian one. This was a young girl who had to learn to read and write, but later, as hostess in her own salon, could competently converse on topical subjects and world affairs with politicians, writers and artists.

Laperouse restaurant. Photo credit © Carl Campbell, Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Life as a successful Paris courtesan opened doors that were utterly inaccessible to an ordinary dame de la nuit. With the protection of their wealthy and often titled patrons, courtesans frequented the illustrious Jockey Club, the Opera, and the fashionable Café Anglais, which was a particular favorite among the wealthy and the aristocracy. (Although the 22 discreet, private rooms may well have added to the allure of the renowned menu.) Another favorite restaurant famed for its private, richly ornate upstairs dining rooms was the famously decadent Lapérouse at 51, quai des Grands Augustin in the sixth arrondissement. (Happily still in existence.)

Marie Duplessis differed from some other courtesans– who perhaps had made long-term plans for when their looks had faded, accumulating wealth and property as a pension– in that she needed no such forward planning. By the time she was 20 and had met the Count de Stackelberg, she already had tuberculosis, which in the 19th century, was an almost certain early death sentence. Marie determined to lived what was left of her life to the full. She spent more money than she was ever given, entertained lavishly, and her warm character was such that her patrons adored her even after their affairs were over. In 1844 Marie became the mistress of the son of Alexandre Dumas until 1845 when she met Franz Listz who fell in love with her while giving her piano lessons. She married briefly the comte de Perregaux and both the comte and her former lover Gustave Ernst von Stackelberg were with her when she died in February 1847.

Marie Duplessis was 23 years old. Alexandre Dumas immortalized her as Marguerite Gautier in La Dame aux camélias, and Verdi was so moved by the novel that he wrote La Traviata, the opera of Violetta, a courtesan with tuberculosis.

Marie’s funeral was attended by hundreds of mourners. She was buried in Montmartre cemetery.

Original photograph of Cora Pearl by Eugène Disdéri. Photo credit © Eugène Disdéri, Wikipedia. Public domain

Cora Pearl (Eliza Emma Crouch), 1836-1886

Cora Pearl was an import to Paris. At the time putative courtesans gravitated to Paris from countries like Russia and Italy, convinced that their unique talents would be best served in France’s capital city. They weren’t wrong.

Eliza Emma Crouch was born in Plymouth, England and although certainly not blighted by the same poverty as say, Marie Duplessis, Cora’s life was irrevocably changed when her father left her mother and married someone else. He then abandoned both families and set sail for America. When Eliza’s mother brought another man into the household, a new stepfather,Richard Littley, Eliza was sent to a boarding school in Boulogne. Whether Eliza was already a headstrong child is not possible to ascertain, but she described her convent education as being more than a religious experience. She returned to London, but this time to live with her grandmother who took religion a little more seriously than her erstwhile school friends. Consequently the boundaries of Eliza’s new life– reading to an old woman and going to church each Sunday– soon stifled her. We only have Eliza’s version in her memoirs, describing her unintentional fall from grace and the new career that swiftly followed. It went like this:

When the maid who accompanied Eliza to church did not appear one Sunday, Eliza set off to explore London alone. She accepted the offer of a drink from a man called Saunders, who had been following her in the street, and woke up the next morning in a bed upstairs in the drinking den. Eliza claimed that she had been drugged, which of course was possible, but whatever the truth, Saunders had left her five pounds. Eliza determined that as she was now “ruined” so she could never return home again and since five pounds was more than she could earn as a milliner for weeks of soul-destroying work, the choice for Eliza was not a difficult one.

Eliza Emma Crouch was now relegated to the past and Cora Pearl emerged seamlessly from her ashes. Being both pragmatic and ambitious, Cora soon became the lover of Robert Bignell, the owner of the Argyll Rooms in London. Cora already had a taste for the high life and an even bigger appetite for money, and when she accompanied Bignell on a tour of France after spending 200,000 francs of his money, she sent him back to England alone. She had known instinctively that Paris was her natural home, where she belonged as she could nowhere else in the world, and where she would rise in spectacular fashion in her chosen profession.

Descriptions of Cora Pearl differ wildly. It would be fair to say that her face divided opinion, but where opinion was unanimous was in descriptions of her body which, in every account, was “second to none.” Her physical allure was so overwhelming that faults normally unacceptable for a successful courtesan became part of her attraction. She could be uncouth and earthy. She was an exhibitionist and a superb horsewoman. (Her detractors claimed that she walked bow legged like a jockey). Fiercely independent, she was not seeking marriage and– perhaps more importantly– did not give a damn what anyone thought of her.

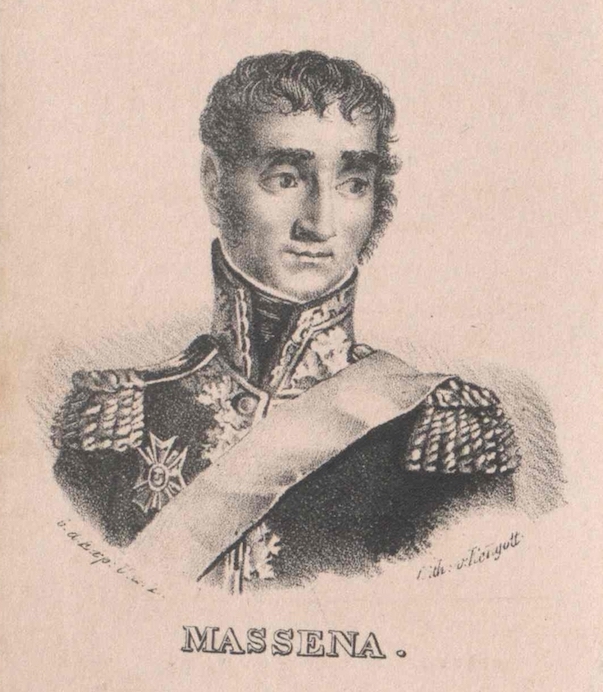

Masséna, André Duc de Rivoli Prince d’Essling. Photo credit © Austrian National Library, Picryl. Public domain

A certain Monsieur Roubisse with connections to the upper class had set Cora up in suitable accommodation and taught her the rudiments in refining and broadening her repertoire of professional skills. (In other words, this monsieur was a high-class pimp.) One of these “introductions” was Victor Masséna, the Duc de Rivoli (later Prince of Essling). Cora described their relationship as the first link in her “chain of gold.” This first link, which lasted six years, propelled Cora into a life of opulence, even Cora could not in her wildest dreams have imagined. Masséna set her up with money, jewels and servants and paid her gambling bills. Cora instinctively knew how to entertain in a grand manner, and with Masséna’s wealth behind her, she was soon spending obscene amounts of money. In just two weeks entertaining at Vichy, the household bill topped 30,000 francs, and Cora became the most sought after courtesan in Paris. She became the mistress of the Prince of Orange, Ludovic, Duc de Gramont-Caderousse and the half brother of the Emperor Napoleon III, Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte.

Bonaparte bought Cora several homes including a palace, Les Petites Tuileries. Prince Achilles bought Cora her first horse. It was soon joined by another 30 Cora stabled behind her house in Rue de Ponthieu. (It was estimated that over a three-year period Cora spent more than 90,000 francs with one horse dealer.)

Cora’s suitors were forced to offer higher and higher sums of money for her favors and more inventive gifts to please her. She had a jewelry collection worth one million francs, owned three homes and was dressed by the couturier Worth. One single night with Cora could cost as much as 10,000 francs.

It was L’Affair Duval that was to provoke Cora’s decline as a courtesan. An affair with the obsessed, extremely wealthy Alexandre Duval, who was 10 years younger, ended in disaster for Cora’s reputation and finances.

The young Duval had spent his entire fortune on Cora and when she finished with him, Duval snapped. Intending to shoot Cora, the gun misfired almost killing Duval instead. The publicity and scandal that ensued caused the authorities to order Cora out of the country. The final nail in Cora’s coffin came in the shape of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, which not only heralded the end of the Second Empire, and the birth of the French Third Republic, but also the end of an era for Cora, with its resurgence of conservative values replacing aristocratic privilege.

Napoléon Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte painting. Photo credit © Hippolyte Flandrin, Wikipedia. Public domain

In 1874, her longest patron, Prince Napoleon, ended their relationship. Cora had been profligate with her fortune, and no longer able to attract aristocratic patronages, she was compelled to slowly liquidate her houses and her jewelry. Her decline was brutal and by 1883, Cora had come full circle and was once more a common prostitute receiving clients in an apartment above a shop in the Champs-Élysées.

Despite this ignominy, Cora Pearl still managed to leave a legacy, not a monetary one, but one in the form of her autobiography, the Memoires de Cora Pearl, which was published in Paris in 1886 and later in London. Famous names were altered but in the main eminently recognizable. She did not censor intimate details however, and the book remains a testament to Cora’s ambition, inhibitions and superb skills as a courtesan.

Cora Pearl died not longer after the publication of her memoirs in July 1886 and was buried in Batignolles cemetery.

Marie Duplessis and Cora Pearl were just two of the famous courtesans who were made famous and wealthy in Paris, a city that reveled in their exploits, applauded their sexuality– as fascinated by them as their influential patrons had been.

Of course other names have also gone down in legend: Ninon de Lenclos, Jeanne Granier, Liane de Pougy, Rosalie Duthé, Claudine Guérin de Tencin, Marie-Louise O’Murphy (one of the lesser mistresses of Louis XV), and the Marquise La Païva, known with good reason as the hardest and cruelest of them all. Despite the changing eras, and moral beliefs of the times, these historical figures were the unarguable proof that sex plus a certain “je ne sais quoi” would always remain a lucrative and unchangeable currency.

Lead photo credit : Cora Pearl and Prince Achille Murat (1865). Photo credit © Louis-Jean Delton, Wikipedia. Public domain

More in french women, Parisian history

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY