The Miracle Courts: Paris’ Notorious Neighborhoods in the 17th Century

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Paris in the 17th century was not a safe city to live in. The streets were mostly unpaved and there was no street lighting. Add to that a street plan that had barely evolved since the Middle Ages and you had the perfect combination for criminals, prostitutes and beggars to thrive. All law-abiding citizens made sure they were safely at home when dusk fell, and even during daylight hours they had to be constantly on their guard against cutpurses and footpads.

Petty criminality was so pervasive it formed its own self-contained sub-society. Whole communities survived in separate neighborhoods across Paris, each with a strict hierarchy, rules and regulations. They hid in squalid, slum courtyards and ancient buildings, generally known as the Cours des Miracles, or Courts of Miracles.

But what, exactly, were the Miracles? Ah, well, you see, these beggars and thieves weren’t quite what they seemed. By day they would appear to be crippled, blind, or otherwise horribly disfigured, all to play on people’s sympathy. At night, back home, off would come the bandages, crutches thrown in the corner, eyepatches removed. “Miraculously” they were not disabled at all.

Jacques Callot, The Beggar with the Wooden Leg (1622). A realistic vision of the beggars of the time on crutches, by an artist from the era of the Court of Miracles. Public domain

Cours des Miracles had existed since the Middle Ages. The late-medieval poet François Villon was well-acquainted with the courts around Les Halles and wrote poems about them. Their peak, though, came in the 17th century. Thousands of impoverished rural migrants, fleeing years of failed harvests and uprooted by war, poured into Paris in search of work – itself in short supply. Inevitably, many of these migrants fell into destitution and were forced to turn to crime. By the reign of Louis XIV, the courts had extended beyond their medieval origins in and around Les Halles to establish themselves throughout the modern 1st, 2nd and 3rd arrondissements.

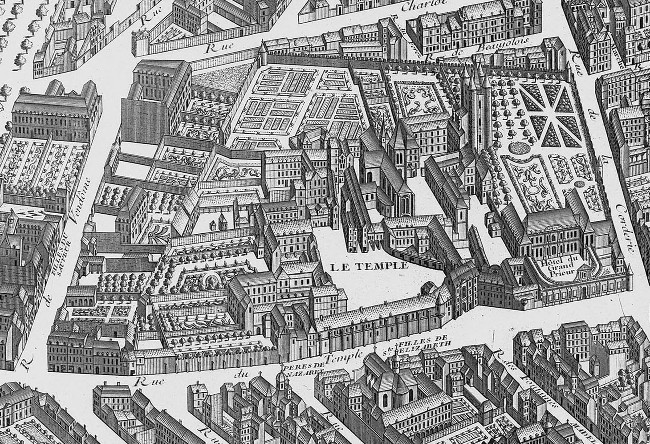

The district between modern Rue and Passage du Caire and Rue Réaumur was known as the Grand Cour but Rue du Temple and Rue des Tournelles were also notorious for their cours des miracles, as was the area between Rue Saint Denis and the Rue de la Forge, which was the site of the rather inaptly named Filles-Dieu Convent (Daughters of God).

The Temple area in 1734 – detail of the Turgot map of Paris. Public domain.

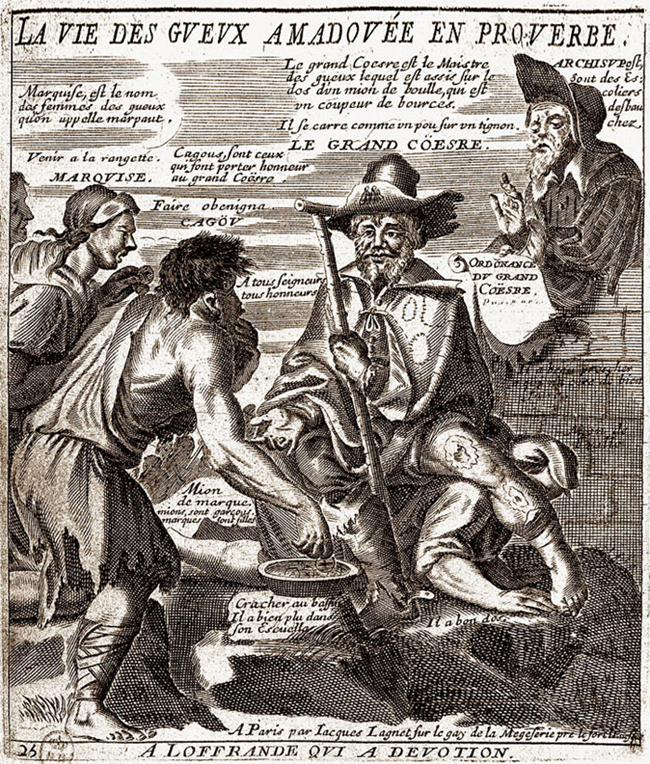

Much of what we know about the cours in this era comes from a historian called Henri Sauval. Like an early urban anthropologist, Sauval trawled the courts and recorded the lives and subculture of their inhabitants. He is the person who popularized the idea that each court had its leader, the chef-coësre, to whom the other inhabitants had to give a portion of their earnings – a tithe, basically – and who set the rules of behavior. There is some debate about how reliable Sauval was as an historian and there are a lot of unsubstantiated claims in his work. One is that a whole hierarchy of seniority below the chef-coësre existed, as well as various “classes” of beggar, such as those impersonating ex-soldiers who had lost a limb in service, epileptics, pilgrims, or victims of a house fire or road accident.

Another claim is that the courts used more experienced criminals to train newcomers and young people as apprentices in a strict hierarchy mirroring the legitimate guilds and apprenticeships of the city. This was completed with a rite of passage in which an initiate had to commit a robbery in plain sight. At the point of lifting the purse his comrades would raise a cry, “Thief!”, and in the ensuing confusion a thieving free-for-all would take place. If the apprentice survived the wrath of the crowd he would be accepted into the thieves’ brotherhood.

The “great Coësre”. Engraving taken from the Collection of the Most Illustrious Proverbs divided into three books: the first contains moral proverbs, the second joyful and pleasant proverbs, the third represents the life of beggars in proverbs, Jacques Lagniet, Paris, 1663.

Yet another claim is that ex-students known as archissupots taught newcomers the obscure slang – argot – of the community. There is probably some truth in all of this: the link between disaffected students and the criminal underworld at this time was well-recorded, and the idea of old criminals training young children recalls Fagin and the Artful Dodger in Charles Dickens’ novel Oliver Twist. Moreover, the Cockney rhyming slang of East London is said to have developed as a way of hiding criminals’ communication from the authorities. There is no reason why Paris did not have its own versions of all of these. Sauval also commented on the general licentiousness and heathen behavior of the people, where marriage, baptism and taking the Sacrament in church were unknown.

Portrait of Gabriel Nicolas de La Reynie by Pierre Mignard. Wikimedia Commons

The situation worsened throughout the first half of the 17th century, until the authorities began to take control from around 1667 onwards. Paris’s first Chief of Police was appointed: Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie. And the city’s first police force was established. Over the following 100 years the cours des miracles gradually disappeared, victims of a combination of better law enforcement and improvements in housing and social conditions. The ancient slums were demolished and the areas repopulated by respectable tradespeople like blacksmiths, furniture makers and food sellers.

The Revolution brought with it new ideas about the perfectibility of man and the role of education and healthy living conditions in fostering public-spiritedness, encouraging more urban redevelopment. Finally, Haussmann’s radical reshaping of Paris in the mid-19th century finally got rid of the last vestiges of the insalubrious neighborhoods that had bred the courts. In turn, this 18th- and 19th-century housing became slums as well and ironically, some may say that the spirit of the courts still exists in the problematic “no-go” housing projects of some of Paris’s banlieues which replaced it.

rue Saint-Sauveur in the beginning of the 20th century. Photo credit: Eugène Atget/ Public domain

Today, the cours des miracles live on only in literature and street names. The rues de la Petite and la Grande Truanderie recall their earlier reputation (a truand is a brigand) and both The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Les Misérables by Victor Hugo describe the cours des miracles in detail. A whisper of the old culture survives in the small number of street prostitutes who still work on and around rue Saint Denis. But as you wander the narrow streets and passageways around rue Greneta, rue Saint Sauveur and rue Tiquetonne, or rue d’Aboukir and rue du Caire, it is not difficult to imagine yourself back in the 1600s, on the lookout for someone jumping out of the shadows.

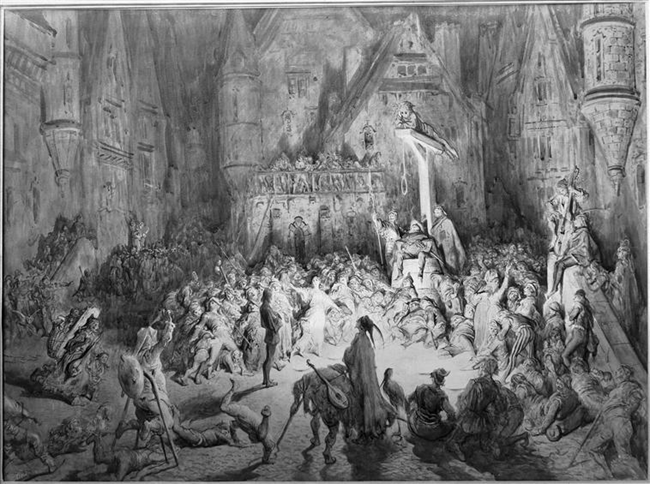

Lead photo credit : The Court of Miracles. Gustave Doré's illustration of Victor Hugo's novel, Notre Dame de Paris. © Gustave Doré/Wikimedia Commons

More in cours des miracles, Paris history

REPLY