Le Chat Noir and the Historic Cabaret Scene in Montmartre

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The audience sits in edgy anticipation sipping wine, as the emcee leans towards them from his chosen vantage point. Everyone laughs nervously, hoping not to be a target of the man’s acerbic wit, as he mercilessly ridicules topics ranging from society, politics and public figures. He holds up social habits for examination, forcing the audience to recognize themselves in the tirade. You could be a participant in a 21st-century stand-up alternative comedy show; instead, imagine yourself in the Montmartre cabaret Le Chat Noir in late 19th century Paris.

Still under martial law after the tragedy of the Paris Commune, Paris was literally and metaphorically in ruins. The Latin Quarter, with its huge student population on the Left Bank, was an area known for its bohemian culture and lively social scene in the 1870s. In an effort to improve the economy, strict regulations controlling public assembly and the establishment of bars were lifted. Anyone with capital could open a bar knowing it couldn’t be closed down on political grounds. Bars and cabarets thrived, becoming bureaucracy-free meeting places for people from all walks of life to engage in drunken debate.

Among the first generation to benefit from the relaxation of laws was a group of young writers and artists known as the Cercle des Hydropathes. (The society’s name described “those who are afraid of water and only drink wine or beer.”) Led by Emile Godeau – a French journalist, novelist and poet, who offered them his Rive Gauche place to hold their meetings – the Hydropathes drank heavily in the bohemian way of that time, green absinthe being the favorite. Here, influential writers, musicians and a young generation of poets were able to unite and develop their artistic talents, performing original works regardless of quality.

Caricature of Achille Mélandri, by Georges Lorin, in the journal Les Hydropathes (25 June 1879, no 12). Public domain

In spite of the alcohol (or maybe as a result of it!), the short period of the Hydropathes (1878-1880) revived a golden age of literacy, creating a new, wider public. The Hydopathes soon outgrew Godeau’s premises. He planned to lift spirits even further by moving to Montmartre. When Impresario Rodolphe Salis invited him to the inauguration of his new cabaret, Godeau swiftly joined him in his enterprise. The hierarchical nature of French society made it difficult for people of different social backgrounds to meet. The two entrepreneurs created a cabaret venue that also promoted poetry and art, where different sectors of Paris society could mingle undisturbed.

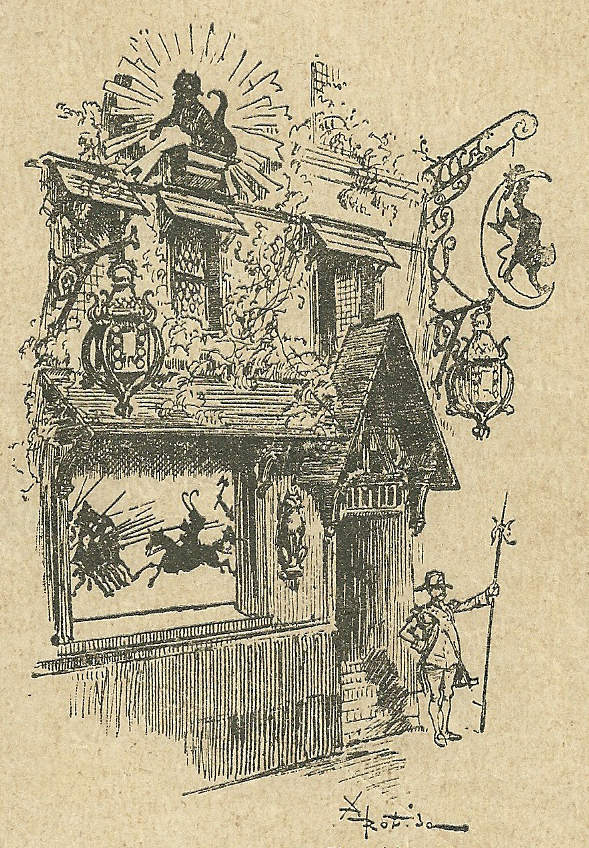

Originally Salis anticipated opening a café evoking Louis XIII-style establishments. In reality he settled for opening a tavern called Le Chat Noir (The Black Cat) in a poorly decorated, two-roomed building at 84 Boulevard Rochechouart in November 1881. (The cabaret subsequently changed locations over the years.)

Portrait of Rodolphe Salis. Atelier Nadar — Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public domain

Initially, Le Chat Noir did not enjoy great fame, lacking refinement and elegance. Whereas the Hydropathes was a club open to anyone who wanted to try out their skills, the Chat Noir was far more selective. The doorman – dressed as a Swiss Guard in gold from head to toe – would not be out of place on the doors of a decadent modern nightclub, conducting artists and poets to their tables while acting as a bouncer to keep out priests and the military.

Only poets, painters and artists were allowed inside. There was a clear line between artists and the public; many people were left at the door. With its location in Montmartre, the Chat Noir became one of the most enduring symbols of bohemian culture of the 1880s and 1890s, establishing Godeau’s reputation as an entrepreneur and visionary, who took advantage of Montmartre’s commercial as much as its cultural environment.

The Chat Noir cabaret by Albert Robida. Public domain

A daring venture at the time, it soon became a cultural phenomenon. It’s still regarded by many as the birthplace of modern cabaret, elements of which can be seen today in stand-up comedy acts. It was the “Live at the Apollo” equivalent of its time. A compere -after interacting with and embarrassing the audience- then introduces acts which continue to provide satirical vignettes of anything worthy of attack!

Salis acted as impresario and emcee, shouting out greetings to customers often at their expense. Even the future King Edward VII, Prince of Wales, did not escape his scathing humor when Salis drew attention to him as he entered Le Chat Noir one evening. Salis liked to call himself “a gentleman tavern-keeper,” and he opened Le Chat Noir at the height of the Decadent Period, said to have begun with Baudelaire’s translation of Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Black Cat.”

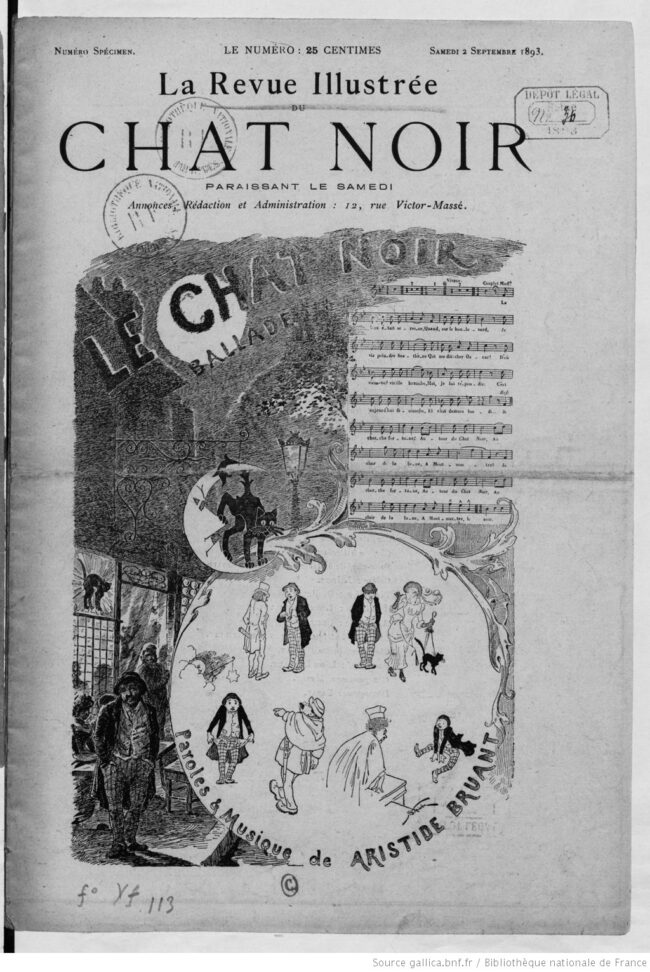

In a flamboyant show of sensationalism tempered with a razor-sharp wit, he named his cabaret after Poe’s story of a black cat, sometimes gentle, sometimes malicious. The story also reveals Poe’s anti-feminist views and is a warning against the dangers of alcoholism. The chauvinistic, burlesque, inebriated side of Montmartre was celebrated in a newspaper launched in 1882 by Salis and Godeau to promote the cabaret.

The illustrated revue, Le Chat Noir, 1893. Public domain

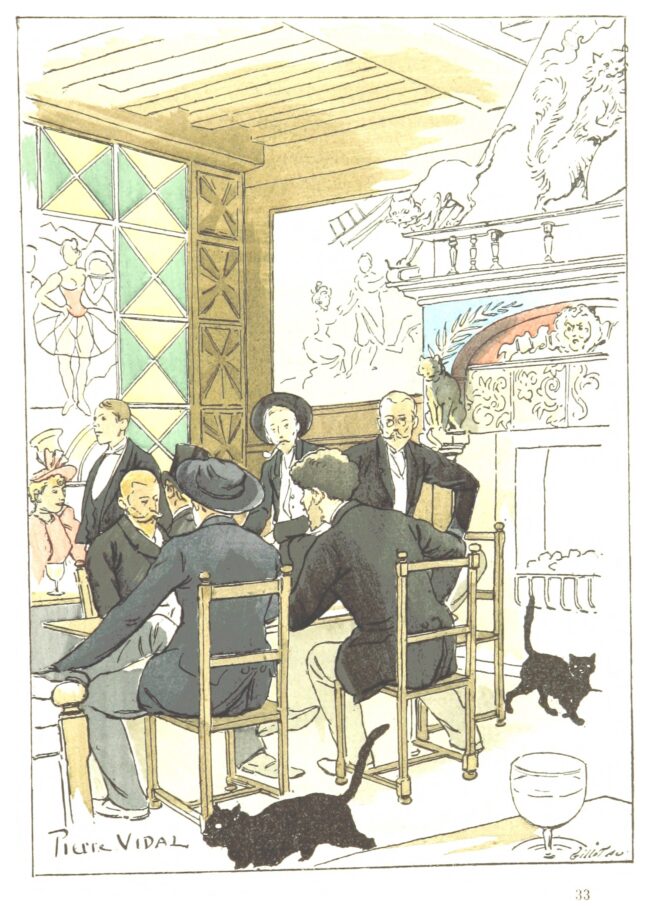

In its heyday, the Chat Noir was part salon, a nod to the social and intellectual gatherings of the 18th century, and part rowdy music-hall. Soon artists and singers who performed at Le Chat Noir found it was the best place in Paris in which to show off their talents. Its evenings were filled with poetry performances, sentimental and satirical songs, stories and improvised monologues, irony and humor. Sipping boozy beverages, the customers settled in for a night of raucous entertainment. Salis had the innovative idea of playing music in his tavern by installing a piano, giving him a huge advantage over any competition.

At the forefront of performers was Maurice Rollinat, a young poet/musician from Chateauroux, who had come to Paris ostensibly to work as a civil servant, but really because Paris fascinated him. As a young man, he was encouraged by George Sand, a very close friend of his lawyer father, to publish his poems. His first love was writing poetry in the style of the “realist” movement in art and literature, before immersing himself in the “decadent” movement. Paris fascinated him almost as much as his fascination with the works of Edgar Allan Poe and Baudelaire.

Maurice Rollinat. Photographer unknown. Public domain

In 1871, leaving his job as a law clerk, he moved from Orléans to Paris, where the Hydropathes – the literary group which he helped establish – became the perfect forum for his writing. On its relocation to Le Chat Noir, Rollinat immersed himself completely in the ideas of the cabaret, performing his own poems on the piano and also those of Charles Baudelaire which he had put to music. His themes were dark, including the horrors of death and dying – themes which still haunted Paris after enduring the trauma of war.

A pale, gaunt man, Rollinat gave electrifying performances. He was described as “contorting his mouth into a satanic sneer” as he sang to well-known faces in the audience including Sarah Bernhardt, Oscar Wilde and Leconte de Lisle.

Au Chat noir, drawing by Pierre Vidal (1849-1913). Public domain

Emile Godeau said that Rollinat’s incredible success was achieved by “torturing the nerves of his audience and creating an intensely physical connection between poet and audience.” In November 1882, Sarah Bernhard organized a soireé introducing him to the Paris elite. It launched Rollinat’s career, bringing him the fame which he had only dreamed of. Picture the star, seated at his piano, wild mane of dark hair, head thrown back, mouth wide open, completely engrossed in his performance, transporting his rapturous audience. I’d liken him to a 19th-century Freddie Mercury in a risqué Paris cabaret.

This young Berrichon poet and musician enjoyed three brief years of the kind of fame associated with pop stars. During this famous session at Le Chat Noir, he was such a triumph that he was mentioned on the front page of Le Figaro. Albert Wolffe, a critic, described his voice as not the kind which the conservatoire would appreciate but coming “straight from the soul” and going “straight to the hearts of the audience.”

Rollinat met Oscar Wilde; Victor Hugo invited him to dinner; Barbey d’Aurevilly described him as “a visionary poet.” Artists loved his face and numerous portraits of him were painted with photographers queueing to capture his image.

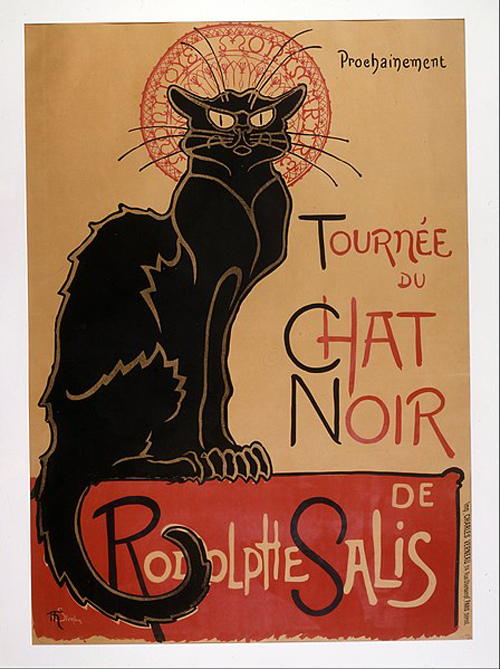

Théophile Steinlen: Tournée du Chat noir, 1896. Public Domain

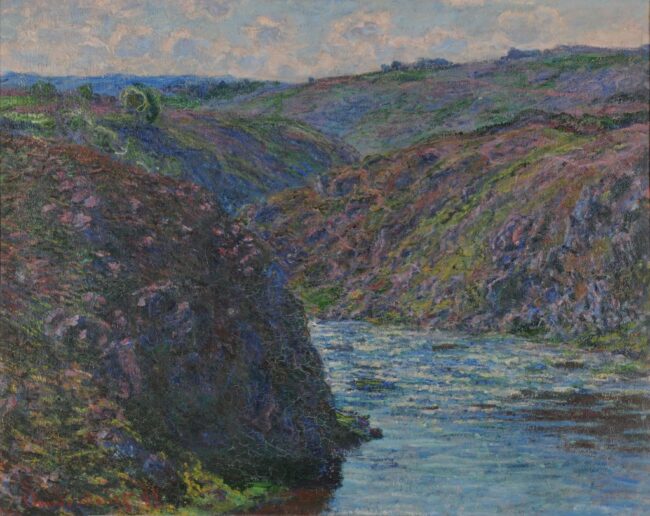

It was an unbelievable, albeit fleeting, success for Rollinat. In 1883, he abruptly left Paris to return to his country roots. Disillusioned by his emerging celebrity based purely on his cabaret performances and Hydropathes affiliation, he was disappointed by the poor reviews of his poetry collections. He settled in Fresselines in the Creuse where he continued to write poetry, and opened his home to Claude Monet and other Impressionist painters who painted en plein air.

Claude Monet, Les Ravins de la Creuse, Fresselines – 1889. Musée des Beaux-Arts Reims.

In 1885, Salis moved Le Chat Noir to new premises at 12 Rue Victor-Masse, previously the lavish mansion of the Belgian painter Alfred Stevens. It closed finally in 1897 just after Salis’ death, by which time the fascination with Montmartre had diminished and the artists dispersed. It is still remembered today thanks to the iconic poster painted in 1896 by the artist Théophile Alexandre Steinlen. Featuring an Art Nouveau-styled black cat sitting on a red ledge against an ochre background, arching its back and staring hypnotically with its piercing yellow eyes at the viewer, it captures the mystery and allure of the cabaret on whose stage artists such as Erik Satie and Claude Debussey performed. Le Chat Noir disappeared but remained an inspiration for the cabaret movement, ensuring its place in the history of Paris nightlife.

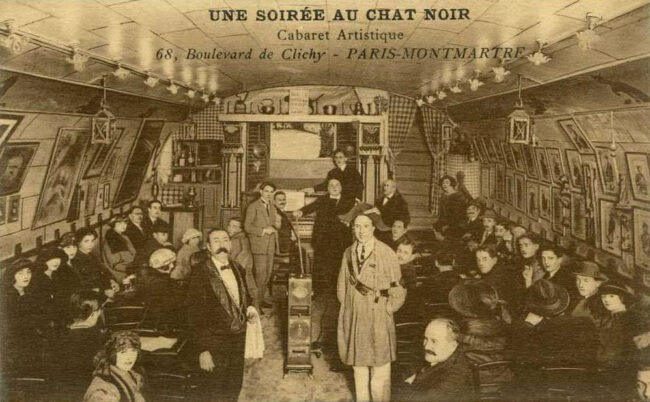

In 1907, a new café called Le Chat Noir opened at 68 boulevard de Clichy. Now the site of a hotel by the same name, it incorporates Steinlen’s poster into its neon sign – an evocative reminder of the artistic rebellion of late 19th-century Montmartre, immortalizing the essence of Le Chat Noir, and an enduring image of Belle Epoque Paris.

Sources and further reading

Maurice Rollinat. Ses amitiés artistiques. Musée Hotel Bertrand° Chateauroux. éditions joca seria.

Albert Wolff, Le Figaro, jeudi 9 novembre 1882. Cité par Régis Miannay dans l’appendice critique des Névroses, Minard, « Lettres Modernes », 1972, p. 404.

The surprising story of the Cat Obsessed Artist Behind the Famed Poster

Le Chat Noir c. 1920. Public domain

Lead photo credit : The first venue for Le Chat Noir on boulevard de Rochechouart

More in cabaret, Claude Monet, Creuse, Hydropathes, Le chat noir, Maurice Rollinat, Montmartre