George Orwell’s Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Rue du Pot de Fer, Paris. © Matt Casagrande & Creative Commons

From the pretty Place de la Contrescarpe, tourists and regular French shoppers in their hundreds make their way each Saturday down the Rue Mouffetard, to one of the most famous street markets in Paris, le marché Mouffetard.

The narrow sloping street is filled with multicultural restaurants, alongside fruit and vegetable stalls, fresh fish stalls and specialist cheese and bakery shops which attract queues of people who spill out over the already crowded pavement.

Rue Mouffetard – Façade original des magasins dans Paris. © Creative Commons & besopha

This little slice of the Latin quarter, a short walk from the Pantheon in the 5th arrondissement, with the Jardin des Plantes on its doorstep, is a much sought after area to both live in and meet up with friends at night.

Walking down from Place de la Contrescarpe, the tiny Rue du Pot-de-Fer is on the right– one of the most ancient streets in Paris. Buzzing with restaurants and small hotels, it is hard to imagine that number six was the home to George Orwell when he wrote Down and Out in Paris and London; this is the street he called the Rue du Coq D’Or.

Café Delmas, 2 Place de la Contrescarpe, 75005 Paris, France. © Matt Casagrande & Creative Commons

In 1928, Orwell described the Rue du Pot-de-Fer (Rue du Coq D’Or) where he lived for almost 18 months in rather less than enthusiastic terms:

“All it was a very narrow street, a ravine of tall, leprous houses lurching towards each other… All the houses were hotels and packed to the tiles with lodgers, mostly Poles, Arabs and Italians. At the foot of the hotels were bistros where you could be drunk for the equivalent of a shilling. On a Saturday night about a third of the male population were drunk.”

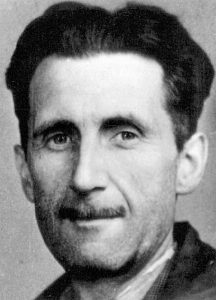

Picture of George Orwell which appears in an old accreditation for the BNUJ. Courtesy of © BNUJ & Creative Commons.

“My hotel was called the Hotel des Trois Moineaux. It was a dark rickety warren of five storeys cut up by wooden partitions into 40 rooms. The rooms were small, arid, and inveterately dirty. The walls were as thin as matchwood and to hide the cracks they had been covered with layer after layer of pink paper which had come loose and housed innumerable bugs. Near the ceiling long lines of bugs marched all day long like columns of soldiers and at night came down ravenously hungry so that one had to get up every few hours and kill them in hecatombs.”

Fights were common, the bistros mostly rancorous dives selling cheap alcohol and rife with prostitution.

Hemingway, who had preceded Orwell by six years, moving into Rue du Cardinal Lemoine on the other side of Place de la Contrescarpe in 1922, never forgot the experience of his first home in Paris and the Cafe des Amateurs, “the cesspool of the Rue Mouffetard” and “the squat toilets of the old apartment houses, one by the side of the stairs on each floor…emptied into cesspools which were emptied by pumping into horse drawn tank wagons at night. In the summertime with all the windows open we would hear the pumping and the odour was very strong, the tank wagons were painted brown and saffron colour and in the moonlight when they worked the Rue Cardinal Lemoine, their wheeled, horse-drawn cylinders looked like Braque paintings. No-one emptied the Cafe des Amateurs though and its yellowed poster stating the terms and penalties of the law against public drunkenness was as flyblown and disregarded as its clients were constant and smelly.”

Ernest Hemingway’s 1923 passport photo courtesy of © Creative Commons.

Hadley, Hemingway’s then wife, described the bistros in the Place de la Contrescarpe as ‘smelly and awful’ where ‘bundles of rags blocked the doorway, then the rags moved, revealing themselves as wine soaked men and women.’

Flower vendors dyed their flowers there and the purple dye would run down the gutters.

Orwell and Hemingway met once as war correspondents in Paris in the 1940s, whether their shared experiences in the Place de la Contrescarpe were exchanged is not recorded.

From the squalor of the ‘Rue Coq D’Or’, Orwell’s circumstances did not improve in his working life. Sometimes going without food for up to three days and pawning his clothes a regular occurrence, Orwell was grateful for finding a job as a plongeur, (washer up) in one of the ten most expensive hotels in Paris at that time. Orwell discreetly called it Hotel X.

One can only be hugely relieved to not have been in Paris in the 1920s and inadvertently have dined in the Hotel X.

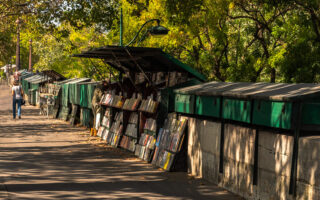

Rue du Pot-de-Fer in Paris courtesy of LPLT & Creative Commons.

“Behind the double door to the dining room-spotless table cloths, bowls of flowers, mirrors and gilt cornices and painted cherubs- and here just a few feet away, we in our disgusting filth- we slithered about in a compound of soapy water, lettuce leaves, torn paper and trampled food. A dozen waiters with their coats off showing their sweaty armpits, sat at the table mixing salad and sticking their thumbs into the cream pots.”

Orwell brings to life the true horror of ordering an expensive steak in the Hotel X, in a passage guaranteed to make one consider vegetarianism as the only option.

“It is a mere statement of fact a French cook will spit in the soup and a steak for instance, when brought to the head cook’s inspection, he does not touch it with a fork- he picks it up with his fingers and slaps it down, runs his thumbs around the dish and licks it to taste the gravy, runs it round and licks again then steps back and contemplates the piece of meat like an artist judging a picture, then presses it lovingly into place with his fat, pink fingers which he has licked a hundred times that morning. When he is satisfied, he takes a cloth and wipes his fingerprints from the dish and hands it to the waiter. And the waiter of course, dips his fingers into the gravy- his nasty, greasy fingers which he is forever running through his brilliantined hair.”

Orwell’s wages were pitiful, his working hours– like all plongeurs — horrendous. Only the free or stolen food from the kitchens and the daily allowance of wine, made it possible to only just scrape by week by week.

Politics and the English Language and Down and Out in Paris and London, vintage Orwell reissues from Random Penguin, Foyles, St Pancras, Camden, London, UK courtesy of Cory Doctorow/Flickr.

Orwell of course, chose to live like a down and out, (he had an aunt in Paris who although not wealthy would have helped him out and relatives in England certainly rich enough to do the same) and although this cannot negate the real and honest brutality of his existence in Paris at this time, the simple fact that cannot be escaped is that Orwell was from a middle class family, had been highly educated and was a writer.

Orwell had choices.

(As had Hemingway, who made much of his poverty in the Rue du Cardinal Lemoine, while in fact with Hadley’s trust fund and his newspaper earnings he was never seriously in dire straits and their comparative poverty could be romanticized in words.)

Composition with lines and angles, about Ernest Hemingway in Paris courtesy of ©Jebulon & Creative Commons.

So while Orwell shone a light on the living and working conditions of the poorest people in Paris, the drunkards, the prostitutes, the voiceless underclass, all those whom society shunned, he could never have truly felt the utter despondency of the true, hopeless poor for

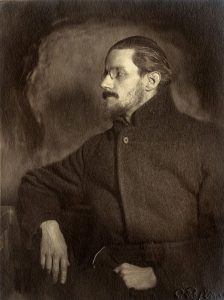

Joyce in Zurich, c. 1918 courtesy of Cornell Joyce Collection & Creative Commons.

whom there was no light at the end of the tunnel, no other talents to drag them from the endless squalor and misery of their day to day lives.

Today the Rue du Pot-de-Fer, Place de la Contrescarpe and Rue Mouffetard are prosperous areas, made famous by Hemingway, Orwell and James Joyce to name but a few; hard then to imagine on a bright summer’s day sitting on a cafe terrace on the Place de la Contrescarpe that less than 100 years ago, this place was the end of the line for so many disenfranchised people.

A place of desperation, a place where hope was a rich man’s commodity and grinding dirt and poverty, the only relentless reality of the poor.

Image Credits: Rue du Pot de Fer, Paris. © Matt Casagrande & Creative Commons, Façade original des magasins dans Paris. © besopha & Creative Commons , Café Delmas, 2 Place de la Contrescarpe, 75005 Paris, France. © Matt Casagrande & Creative Commons, Picture of George Orwell which appears in an old accreditation for the BNUJ. Courtesy of © BNUJ & Creative Commons, Ernest Hemingway’s 1923 passport photo courtesy of © Creative Commons, Composition with lines and angles, about Ernest Hemingway in Paris courtesy of © Jebulon & Creative Commons, Rue du Pot-de-Fer in Paris courtesy of LPLT & Creative Commons, Politics and the English Language and Down and Out in Paris and London, vintage Orwell reissues from Random Penguin, Foyles, St Pancras, Camden, London, UK courtesy of Cory Doctorow/Flickr, Joyce in Zurich, c. 1918 courtesy of Cornell Joyce Collection & Creative Commons.

Lead photo credit : Rue du Pot de Fer, Paris. © Matt Casagrande & Creative Commons

More in French authors, French history, French literature, French writers, Hemmingway, Historical figures, Literature, Orwell

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY