Faux Paris: A Wartime Ruse to Create a Decoy City

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Paris is without doubt one of the most beautiful cities in the world. Part of its continuing splendor is owed to the relative lack of damage during both World Wars. However, during World War I, air attacks on the city were becoming more accurate and more frequent. In 1918, an idea to create a decoy city, a twin to keep Paris safe, had moved from the drawing board to reality.

Silent, stealthy Zeppelins and heavy-duty airplanes called Gothas had been dispatched to the nighttime skies above France. The enemy had bombed Paris in 1914 and 1915 with not only incendiary devices, but also leaflets demanding that French surrender. On January 29, 1916, 17 bombs dropped by a Zeppelin on the neighborhoods of Belleville and Ménilmontant killed 26.

Paris continued to be a target for bombardment in 1917. A bomb flung from a Zeppelin left a substantial crater on a major thoroughfare. In January of 1918, a bombing raid dropped 200 shells, causing death, destruction and another sizeable pothole on Rue Drouot. More raids happened in the spring of 1918; over 70 citizens died as a result of a panicked reaction in the Bolivar Métro. Long-range artillery began firing into Paris. During Mass, one shell hit the centrally located Saint Gervais church killing 82 and injuring many more. Shelling continued into September 1918.

Crater of a Zeppelin bomb in Paris, 1916. Image credit: Willy John Abbot – The Nations at War. Public domain

Despite these attacks on Paris, German pilots struggled to find their bearings. Before planes were equipped with radar, aerial bombardment was imprecise; aviators had to fly purely by sight. When they found their assumed target, bombs were physically thrown onto the unsuspecting population below.

French fighter pilots confirmed this, stating that during night flights they looked for familiar landmarks when attempting to locate their mark. Their findings revealed that rivers, railways and roads were the most useful indicators of their bombing targets.

The mastermind behind the grand scheme to duplicate Paris was an expert electrical engineer named Fernand Jacopozzi. He proposed this idea to the French government early in 1918. Jacopozzi thought it would be easy to divert German bombers away from the real Paris with some crafty visual deception. City officials quickly got onboard; the logic behind an illuminated mock Paris began to take hold.

Fernand Jacopozzi. Credit: Credit: British Newspaper Archive

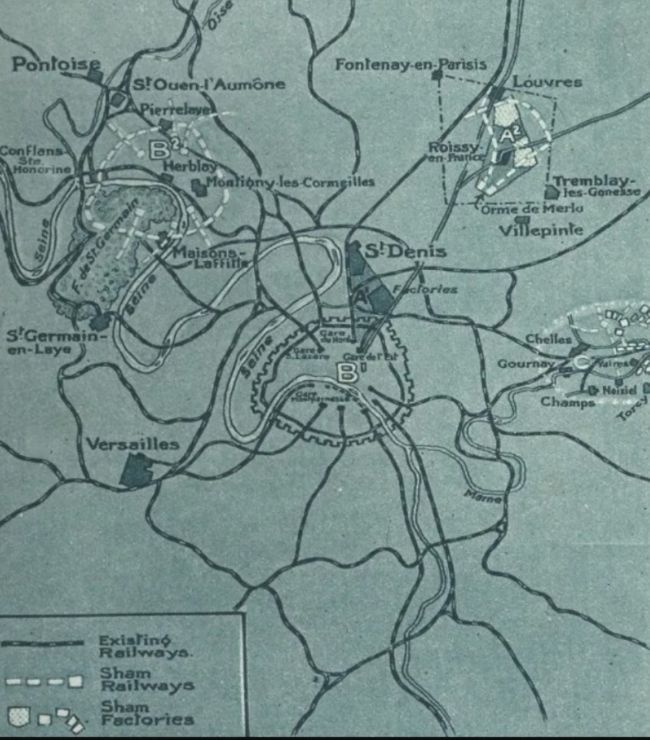

Three sites were to be utilized as Paris’s stunt doubles. Zone A, situated to the northeast of Paris, would mimic the large suburban regions of Saint Denis and Aubervilliers, and would include dummy versions of the train stations Gare du Nord and Gare de l’Est. Zone C built to the east of the city would simulate an industrial area of enormous factories, albeit empty.

However, Faux Paris – Zone B – was to be built within the little suburb of Maisons-Laffitte, 15 miles north of the capital. Maisons-Laffitte was nestled in a similar-looking loop in the Seine and had enough likenesses with Paris to draw the attention of the foe, especially at night.

A team of artists was hired to create the Faux Paris itself built from wood and canvas. Within a sprawling network of buildings replicated the Champ de Mars, the Champs Élysées, and the Arc de Triomphe. The wooden frames of pretend factories were tightly covered with roofs of canvas. Covered with translucent paint, and illuminated from beneath, they looked like the dirty glass skylights of industrial buildings. The same technique was used to replicate the city’s grand train stations. Smoke emanating from factories added an extra dimension of reality. A proposed map of Maisons-Laffitte shows the sham town with a periphery exactly mimicking Paris. It seemed to be enclosed by a railway that circled the city’s outer limits – or was it?

The most important part of the ruse was the lighting. Electrical engineer Fernand Jacopozzi – who would become famous for first illuminating the Eiffel Tower and the grands magasins of Paris – devised a lighting scheme for the new town. In this second City of Light, a wooden train seemed to move along a track as if it were real, but it was in fact part of Jacopozzi’s lighting plan. The glow given off by the interior of a moving train was a series of lights moving in sequence, not the train itself. Red and white lights would mimic cars lined up in the dark. The lights of the pretend factories were even configured to dim noticeably during an air raid, to fool enemy pilots.

While the real Paris was cloaked under a total blackout, Faux Paris had working lights just dim enough to convince attackers that Parisians had just closed their curtains to hide themselves. Looking at the panorama of the real Paris from the third level of the Eiffel Tower, Jacopozzi’s team were able to confirm how Paris really looked at night. In this way, Maisons-Laffitte became a trompe l’oeil of light.

As residents of a now-disposable town, what did the people of Maisons-Laffitte think of the scheme? Was there a plan in hand to evacuate the residents? Luckily, they never faced the terror of bombing, but it could have been a bizarre scene if the Armistice hadn’t been signed before construction could be completed.

Armistice in Paris. © Imperial War Museum

Paris wasn’t built in a day and the fake Paris wasn’t finished by war’s end. The German bombing campaign ceased in September 1918 and the Armistice was signed two months later. After hostilities ended, the government moved quickly to dismantle the mock factories, streets and railways so by the beginning of 1920 little remained of the project at all. They seemed to suppress all information concerning the existence of their secret plan. After the war, just three very short accounts about the secret city appeared in French newspapers. In October 1920, The Globe ran a one-paragraph account in the British press, titled, “A Mock Paris: French Plan to Hoodwink German Raiders.”

Parisians celebrate the end of World War I on November 11, 1918.

Although only a fraction of the fake city was ever completed, Jacopozzi’s faux Paris was a fascinating idea. It might not have diverted a single bomber, but the ambition behind such a project speaks to France’s appreciation of Paris as the locus of French civilization.

Lead photo credit : Paris at night. Credit: Benh LIEU SONG/ Wikimedia Commons

More in Faux Paris, Jacopozzi, World War I, World War II

REPLY