Starting a Business in France: Interview with Craig Carlson, Founder of “Breakfast in America” Diners

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Before and After for the Breakfast in America in the Marais district. (© Craig Carlson and Cedric Roux)

Craig Carlson is the founder/owner the Breakfast in America diners in Paris. Carlson first came to France in 1985 through a study abroad program, and fell instantly in love with the country. When he returned to the U.S. after studying in Paris, one of the many things he brought home with him was a love of cinema, which led indirectly to a five-year career as a screenwriter. Eventually his knowledge of the French language brought him back to Paris as a post-production supervisor on an American TV series being edited in Paris. When he returned to Los Angeles after a year, determined to find a way to return and live in Paris for good, as he ate his first American breakfast in a diner with friends, he realized “that it was the one thing I had missed when I was in Paris.” That “ah-hah” moment led to his perhaps somewhat quixotic idea of opening an American diner in Paris. However, he did it, and he succeeded, quite against the odds; a fascinating, often funny, occasionally nail-biting story he tells in his book, Pancakes in Paris: Living the American Dream in France. The book is a New York Times bestseller, and was selected as Best Book of 2017 by Expatriates magazine. [Read our review here.] Carlson recently took the time to answer Janet Hulstrand’s questions in this exclusive interview for Bonjour Paris.

Janet Hulstrand: Craig, thanks for doing this, and let’s just cut to the chase. What gave you the idea of opening an American-style diner in Paris? And how has that idea gone?

Craig Carlson: I first came to France in 1985 as an exchange student with the “Junior Year Abroad” program at the University of Connecticut. The moment I arrived in Paris, I instantly fell in love with the country, the language, and especially la bonne cuisine. After I had spent time in Paris for the second time, in 2001, I knew what I wanted to do next with my life: I wanted to open an American diner in Paris. I even knew what I was going to call it: Breakfast in America. My lawyer did warn me that the name could be a problem thanks to the 80s rock band Supertramp, which had a multi-platinum-selling album by the same name. But that’s another story: you’ll have to read about that in my book.

Pancakes in Paris

Anyway, the Supertramp problem was nothing compared to all the other obstacles I faced, mainly that I’d never owned my own business before, let alone a restaurant – the riskiest business of all – and certainly not one in a foreign country with a foreign language that just happens to be the culinary capital of the world. But I was so sure of my idea I was determined to make it happen.

In the beginning it was definitely a struggle. Take for example the word “diner.” In French, it means “to dine,” or “to eat dinner.” Many French customers were confused, especially when they’d see our name, “Breakfast in America Diner.” To them that seemed contradictory: I had to teach them the American meaning of the word.

Another challenge I faced in the beginning was that I had no budget for advertising, so I had to rely on word of mouth, which fortunately, spread rather quickly. Once American tourists and the expat community in Paris heard there was an American breakfast joint in town, they began pouring in.

Then there was the challenge I faced with French customers in the beginning. Most of them held a very strong stereotype about American cuisine: that it only consisted of hamburgers and fast food. On a personal level, I wanted to show my adopted country that there was more to American cuisine than burgers. In the beginning we only served breakfast at the diner — breakfast at any hour. But that didn’t last for long. After only a couple of months, my French customers began asking me when we were going to start serving “un vrai ‘amburger, pas MacDo?” (A real hamburger, not McDonalds?) So ironically, the American stereotype I was trying to avoid was quickly introduced to our menu thanks to my French customers!

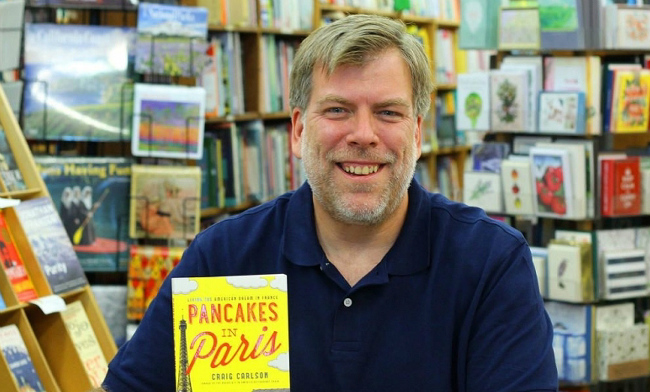

Author and business owner Craig Carlson. Photo: Pancakes in Paris

Not long after that, the French press starting writing articles about us, and thanks to that coverage, it wasn’t long before the makeup of our clientele flip-flopped – with 70 percent of our customers French, and the rest American and other nationalities.

Some Americans have poo-pooed the idea of an American diner in Paris. I’ve read a few online comments that say things like: “If I’m in France why in the world would I want to go to an American restaurant?” Believe me, I completely understand! I love French cuisine, and have always wanted to be integrated into French culture. But it’s a little different when you’ve lived in Paris a long time. Sometimes comfort food can really satisfy the soul. And in my opinion, something like an American diner is not a fast food place. It’s a neighborhood spot where locals of all backgrounds can hang out together and converse for hours. That is what it’s like at BIA. We’ve built a community of French, American, and international customers, many of whom have been coming for years, and who we know by name. That’s something I’m proud of.

Janet: In your book, ”Pancakes in Paris,” you describe some of the ups and downs you had as an American starting a restaurant business in France. One reviewer even described your experience as “Kafkaesque.” Is that an adjective you would use, and if so why? And what was the hardest lesson you learned along the way?

Craig: Yes, Kafkaesque is the perfect adjective… almost. Über-Kafkaesque comes closer.

I’m sure everyone has their own bureaucratic horror stories – including those in the States – but seriously, dealing with French bureaucracy has been beyond my worst nightmare. The main reason, I think, is because the laws – especially the infamous 3,324 page code du travail, or labor code – have become virtually unworkable.

My company consults with a lawyer who specializes in the code du travail, and she openly admits that parts of the code completely contradict other parts, and that it’s impossible to follow things to the letter because there is no consistency. Case in point, when I first opened the diner and hired employees, my lawyer told me that, according to the code du travail, I could give them temporary contracts (called CDDs), which consisted of a relatively short trial period before the position becomes permanent. However, after we got a surprise visit from the inspecteur du travail (kind of like the labor police), he said, (also per the code du travail), “Non, non, non! All of your employees must have a CDI right from the start!” CDIs are essentially lifetime contracts where it’s virtually impossible to fire the employee, no matter what they do, including theft, absence, or even threatening your life. I talk about the latter in my book. The very first employee I hired started off well, but the moment his trial period ended, his behavior became very erratic, especially after he learned he could no longer be fired. But of course, I didn’t know that at the time. So after he threatened to kill me in front of my customers, I fired him. That was a big mistake. Within weeks I was summoned to the labor court. The trial went on for over a year, and in the end he won, and was awarded thousands of euros, even though he had only worked with us for three months. After the trial, my lawyer told me that one of the reasons I lost was because the employee needed to have threatened my life in three different ways – not just one. Now if that’s not Über-Kafkaesque, I don’t know what is!

To answer the second part of your question, what’s the hardest lesson I’ve learned? Well, in France, I’ve learned there is no black and white. One has to get used to what I call “living in the gray” — a kind of hazy uncertainty in which my French husband, who has joined me in running the business, has no problem navigating. He claims it’s all in what’s not said – the very Gallic sous entendu.

Breakfast in America. (© Cedric Roux)

Janet: One hears an awful lot about how difficult it is for entrepreneurs to be successful in France, but are there any advantages that we don’t hear as much about?

Craig: I love this question! It’s the first time I’ve been asked it. On a purely business level, one huge advantage is that I don’t have to incur the financial burden of paying for my employees’ healthcare, since France has universal coverage. (Incidentally, Warren Buffet, the billionaire American investor, has argued that adopting a single-payer-type healthcare system in the States would actually be good for businesses). That said, since France actually has a two-tiered healthcare system, I am required to pay half of the premiums for each of my employee’s supplemental insurance, which amounts to only fourteen euros per month per employee. Compare that to the cost of health insurance for businesses in America. It’s the same with liability insurance. The U.S. is a much more litigious country, whereas in France work accidents, etc. are covered by the government, which really is a huge benefit to small businesses. And it’s the same with maternity leave, paternity leave, and job training – all of which are (mostly) covered by the government.

On a personal level, I can think a lot of other advantages as well. Given the nature of my business, I can’t afford to pay high wages, but I do have the peace of mind knowing my employees can live well on the salary I pay them, thanks to the benefits built into the French system. For example, I’m required to pay half of the transportation costs for my employees. But fortunately, the public transportation system here is so efficient, it only costs me 35 euros a month per employee. As a bonus, employees get to use their Metro pass outside of work as well. There’s no need to purchase an expensive car and insurance. And if one of my employees has a kid, he or she can get affordable daycare. And all this with just one job! By contrast, I recently read an article in the New York Times about a large subset of Americans, mostly over the age of 40, who have taken to roaming the country, looking for any job they can find. Many of them end up taking on two or more jobs at a time, with insanely long hours, literally working themselves sick – but still unable to afford health insurance.

The last thing I’m going to say will probably shock most American business owners: I’m glad the French government forces me to give my employees five weeks of paid vacation. As a former workaholic, one of the best things France has taught me is the tremendous value of vacations for a well-balanced life. However, if I had to be honest, as a business owner, I don’t think I’d voluntarily take on the huge expense. So many Americans I talk with can’t believe that everyone in France gets five weeks of paid vacation – even if you work at McDonalds. They’re surprised, because American businesses have been saying for years that they’d go bankrupt if they were forced to pay for their employees’ vacations. Well guess what, McDonalds is thriving here in France, and I’m doing okay, so let me be the first to say that even though a business may make a lot less profit, it can definitely afford to pay for its employees’ hard-earned, family-building vacations.

Janet: One of the biggest challenges before the new French president, Emmanuel Macron, is going to be overcoming strong resistance to the reforms to the code du travail he wants to be able to achieve. Can you briefly explain, especially for American readers, what the nature of those changes are, and also what all the fuss is about? Why are these changes so controversial? And what do you think about the situation, given your experience as a business owner in France?

Craig: That’s a tough question, especially given all that I’ve just said about how complicated the laws are here. But to put it as simply as I can, the French know their history very well, and they know how hard their predecessors fought for the rights they’ve gained. Therefore, they don’t want to lose a single “right” – even if some are no longer relevant. Here’s one example told to me by a French friend: Métro train conductors still get a “coal bonus” on their paychecks, even though Metro trains have been running on electricity for decades. “But it’s my right!” they say. “You can’t take it away from me!”

Over time, as pages upon pages of these kinds of rights and perks have been added to the code du travail, many remain that haven’t adapted well with the changing times. That’s what Macron’s been trying to reform. It’s a monumental task that past French presidents have been unable to accomplish. For example, a few years back, President Sarkozy tried to tackle the high rate of youth unemployment by introducing a contract for young adults under the age of 26 (called the CPE) where, during the first two years, they could be more easily fired. Students, including many of my own employees, poured into the streets in protest. I asked one of the protesters, the French girlfriend of one of my cooks, to help me understand why everyone was so upset. “Don’t you see?!” she howled. “With this new contract, you can be fired! C’est scandaleux!” I tried to explain to her that, as a small business owner, I was always looking for good, hard-working employees who would stick around for a while. I wasn’t rubbing my hands together, searching for the next person to fire. She didn’t hear a word I said. She just kept waving her fist and saying how scandaleux it was.

From this you can see how difficult the situation is for Macron. The French will resist any change, no matter how small. And that’s exactly what’s happening now. In my humble opinion, Macron’s proposals are quite insignificant, and won’t put at risk any of the incredible benefits and rights the French have – including five weeks’ paid vacation, universal health care, generous unemployment benefits, free job training, and so on. Macron has proposed things such as putting caps on the amount that labor courts can award employees. Similarly, he is trying to make it slightly easier to fire people (although the details have yet to come out) – as well as make it easier to hire people, which is a whole other topic. Lastly, he’s introduced some proposals that will allow larger companies to make labor decisions internally, instead of having to pass by a large labor board.

Unfortunately, so far none of Macron’s proposals tackle what I think is the second biggest impediment to running a business in France – flexibility. Take France’s infamous 35 hour work week. When I first started my business, I’d just assumed that overtime started from the 36th hour on. But it’s not so. Say you’ve hired someone on a part-time contract for 20 hours a week. Well, for them, overtime starts on the 21st hour. Even worse, nobody is allowed to work more than 20 percent above their contracted hours. That means if someone is on a 20-hour contract, he or she cannot work more than 24 hours — four of which are expensive overtime. So when employees take their five-week paid vacation, how am I supposed to fill the empty slots if I can’t legally increase another employee’s hours to cover it? I think you get the idea… In any case, I welcome any changes Macron can get through, even if they’re the size of a pinhole!

Janet: I think it’s fair to assume that a lot of people would not have persisted in the dream given some of the challenges you faced in making a go of your restaurant. What made you stay the course? And do you have any advice for others who might be in a similar situation?

Craig: I’ve been asked this question a lot – why didn’t I give up after all the challenges I faced? I think there are two reasons. First, my Polish immigrant heritage. My family was made up of very hard workers. My grandmother came to America when she was five and worked in a garment factory her entire adult life, never taking a single day off. From her and from other members of my family, I acquired a strong work ethic.

The other reason I didn’t give up is a little less noble. After I had the idea for Breakfast in America, I got rid of everything I had in the States, including my apartment, my car, and all of my personal belongings, in order to move to Paris. One thing I couldn’t get rid of, however, was my enormous student loan debt and maxed-out credit card debt. So by the time I was in Paris trying to get the restaurant off the ground, I realized there was literally nothing left for me back in the States – except some hungry collection agents. At my lowest point, I remember thinking of that famous line Richard Gere says in An Officer and a Gentleman: “I’ve got nowhere else to go!” So I stayed in Paris and kept moving forward, eventually getting my restaurants opened – and as an added bonus, paying off my student loans and all my credit cards.

Of course, I don’t think everyone who’s pursuing their dream needs to be in the same predicament I was in order to stay the course. What’s most important to succeed, I believe, is the passion you have for your idea. I could see mine so clearly: and I wasn’t going to give up no matter what. So my advice would be to be completely honest with yourself: are you ready, willing, and indefatigably able to commit yourself for as long as it takes to make your dream a reality?

Square René Viviani by Giorgio Galeotti

Janet: What is the thing you love most about living in Paris?

Craig: I know it’s a little clichéd by now, but by far the thing I love the most about living in Paris is the quality of life – both big and small. First the big: being centrally located, it’s so easy – and affordable – to travel around Europe. For my birthday, I spent a long weekend in Budapest. The year before it was Prague. And with a simple high-speed train ticket, you can be in the center of London in just two and a half hours. (I know people in LA whose daily commute to work is that long). As for the small things, there are so many. If I time my mornings right, I can be at my favorite bakery around the corner just as the baguettes are coming out of the oven, all warm and fresh, ready to be smeared with demi-sel butter and my French mother-in-law’s homemade cassis jam. Or I can picnic on the Seine, listening to the bells chime from Notre Dame. If I have a hankering for cheese that’s prohibited in the States, I can walk a block to my neighborhood fromagerie and indulge myself. And on those days when I crave pancakes with blueberries and white chocolate chips drenched in 100% maple syrup from Canada? I know where to get them – for free. How can you beat that?!

Lead photo credit : Author and business owner Craig Carlson. Photo: Pancakes in Paris

REPLY