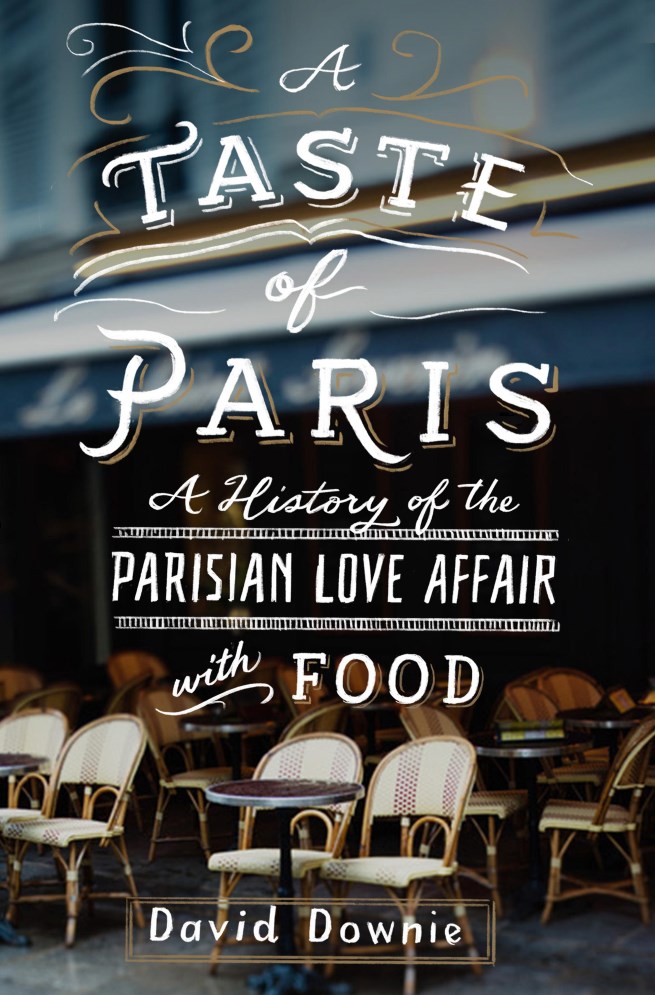

Exclusive Excerpt from David Downie’s Excellent New Book, “A Taste of Paris”

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Established in 1684, Procope is one of the oldest café-restaurants in Paris.

One of the best books to land on our desk recently is David Downie’s A Taste of Paris: A History of the Parisian Love Affair with Food. With humor and wit, Downie delves into the city’s culinary history, sharing fascinating anecdotes (did you know that Louis XIV– a food-obsessed gourmand– lustily consumed 7,000 calories a day?) A Taste of Paris is written in a fun, lively style, bringing to life thousands of years of history, while also elaborating on contemporary culinary trends. As more and more travelers make trips for food, A Taste for Paris is an indispensable guide to the past, present, and future in a city that’s often deemed a global food capital. (Is it still? Read the book for the answer!) Below we share an excerpt. Bon appétit!

On the occasion of the book’s release, BP correspondent Janet Hulstrand interviewed author David Downie; find the fun article here.

Excerpted from A TASTE OF PARIS: A History of the Parisian Love Affair with Food by David Downie. © 2017 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

PASSÉ PRESENT

Strange to say, as the city reached its natural intramural limit during the Second Empire, halted by the bastions of Adolphe Thiers that now mark the beltway, the last growth of the oyster shell, French cuisine also reached a gastronomic frontier broken only by the advent of the new nouvelle cuisine of the late 1960s and ’70s.

Curnonsky, Rouff, Raymond Oliver, and the other great gourmets, gourmands, and gluttons of the first half of the twentieth century looked back- ward, glorifying the past the way their early nineteenth-century forebears glorified Louis XIV, the Regency, and the reign of Louis XV. The Ancient Romans had a name for such a person: laudator temporis acti, one who praises the past. Passéisme was, has always been, is, and probably will always be a distinguishing feature of Paris and Parisians. The nineteenth century and its cooking live on despite the savaging they’ve received over the last forty-five years. Actually they’ve been improved by the savaging, much of it deserved. Today’s new-old cooking is doubtless tastier, more healthful, and delicious than it was in its heavy-handed heyday.

And why shouldn’t the past live on? Without it there’s no present and no future, not in France. Paris is not New York. I’ve never understood why certain people want to turn an orange into an apple—the Big Apple.

And why shouldn’t the past live on? Without it there’s no present and no future, not in France. Paris is not New York. I’ve never understood why certain people want to turn an orange into an apple—the Big Apple.

I’m also not sure how many serious Parisian food lovers are passionate about molecular or the ephemeral haute cuisine d’auteur de rigueur in the Michelin multiple-starred temples of gastronomic hauteur in Paris and elsewhere. Nowadays most of them are filled by migratory Yanks, Brits, Japanese, Chinese, and Russians—not many French. Like post-neo-academism that renders literature sterile or the institutionalized avant-garde that nearly killed the fine arts last century, cuisine d’auteur has become surprisingly predictable and global despite being artistic, extremely technical and difficult, and unique to each practitioner. It’s unreproducible by even the most talented home-cook, rarely comforting, and often discomforting and disconcerting—but so was Cubism a century ago. Acolytes see these as positives, challenges for cool initiates, the new dining elite possessed of artistic sensibilities.

Are they elite? Foodistas and fashionistas seem to blur and merge when they gush about the emperor’s new nouvelle cooking or the latest clothing trend. “Hoodwink,” “smoke and mirrors,” “flimflam,” “snake oil,” “play with your food,” “shock and thrill the bobos,” and other unkind expressions are sometimes used by the uninitiated in the French mainstream press to describe the current style of infantilized top-end restaurant dining. History is a great foil, reminding anyone who studies it that poseurs and pseuds are nothing new. By other names, foodistas and fashionistas have been part of the Paris scene since at least the seventeenth century.

author David Downie

DECLINE AND FALL

Nothing comes from nowhere. Nouvelle cuisine got started in the late 1960s as college students and factory workers were uprooting cobbles and upending the world. It took off like the supersonic Concorde in the mid-1970s, ironically just as the French economy was ending its three-decade postwar bull market. New imported foods and revolutionary cooking technologies were also coming on tap: blenders, mixers, processors, juicers, microwaves, nonreactive pans, frozen foods, and that other genial invention of industrial food preservers, sous vide. Liberated Frenchwomen were casting off their aprons and going to work by the millions, and the first wave of global fast food and convenience crap started hitting Gallic shores. The term malbouffe—lousy, unwholesome junky food—was coined over forty years ago by French writer Joël de Rosnay.

And along came Gault & Millau . . .

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS OF GAULT & MILLAU OR THE MANIFESTO OF NOUVELLE

- Thou Shalt Not Overcook

- Thou Shalt Use Fresh, High-Quality Ingredients

- Thou Shalt Lighten Thine Menu

- Thou Shalt Not Be a Dogmatic Modernist

- Thou Shalt However Try New Techniques and Technologies

- Thou Shalt Avoid Marinades, Long-Hanging of Meats, and Fermentations

- Thou Shalt Eliminate Heavy Sauces

- Thou Shalt Not Ignore Dietetics

- Thou Shalt Not Disguise Thine Foods

- Thou Shalt Be Inventive

The televangelists of nouvelle included the chameleon Paul Bocuse, made Knight of the Legion of Honour in 1975, Michel Guérard, the Troisgros brothers, Alain Chapel, Alain Senderens, Joël Robuchon, Guy Savoy, Marc Veyrat, Pierre Gagnaire, Michel Rostang, and others. All were hailed by Gault & Millau and then Michelin, which saw the way the tires of novelty were rolling.

True to historical patterns, with teeter-totter predictability nouvelle became toxically earnest, preachy, joyless, miniaturized, and unfulfilling. Its emaciated eaters lost interest. A counterinsurgency began: terroir, the return to traditionalism.

By the time I climbed onto the Gault & Millau running boards in the late 1980s, the publication had become neo-baroque and uncharacteristically accommodating, using a laurel-leaf symbol and black toques to designate traditional, regional terroir cuisine. Strangely the places resting on their laurels, so to speak, were the ones I liked best. As a class they’ve survived the supposed decline and fall of French cuisine and many thrive in the twenty-first century.

Dear readers! You can order this wonderful book on Amazon below: