Printemps des Poètes: Paris Celebrates Poetry

Paris and the Île de France have been celebrating poetry this month. The Printemps des Poètes (Poets’ Springtime) has included a whole range of free events ranging from poetry readings and competitions to poetry walks, exhibitions and workshops. As the organizers of this annual festival – now in its 27th year – explain, the aim is both to celebrate the great French poets of the past and to “discover the diversity of contemporary poetry.”

To me, the project sounded so quintessentially French that I had to investigate, so I went along to the Médiathèque Marguerite Yourcenar in the 15th arrondissement where the actor and musician Patrick Hamel was performing his Voyage dans la poésie (Journey into poetry). He recited a wide range of poems from half a dozen of France’s favorite poets, setting many of them to music and accompanying himself on guitar, piano and keyboard. He interspersed the poems with little anecdotes and the evening was, just as the title had indicated, a tour through some of France’s best verse.

To give a flavor of this most enlightening evening, here is a little information on six of the poets Patrick Hamel chose to highlight, along with an introduction to one poem for each of them, along with an approximate English translation. Some of these are poems he performed on the night, while others are just personal favorites of mine. I hope they make you feel you are taking part in the Printemps des Poètes!

Patrick Hamel performing ‘Voyage dans la poésie.’ Photo credit: Médiathèque Marguerite Yourcenar/ Ville de Paris

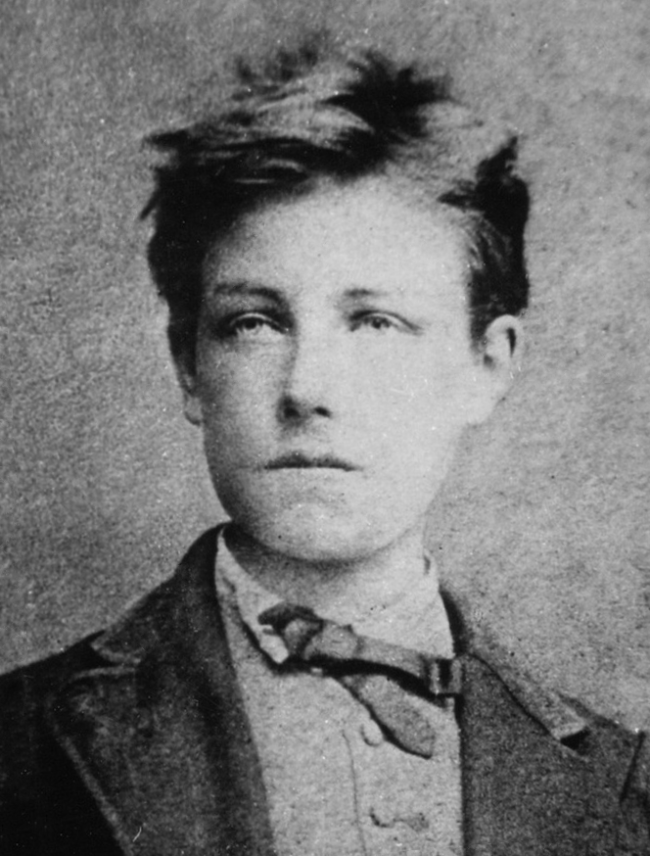

Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891) led a turbulent life, fleeing his hometown to fight in the Paris Commune, abusing alcohol and drugs and scandalizing society through his affair with the poet Verlaine, who eventually shot him during an argument. After that, he went on a number of unlikely adventures abroad, to the Dutch East Indies and Ethiopia for example. While abroad, he developed a tumor on his knee and returned to France where his leg was amputated before he died in a hospital in Marseille at the age of only 37.

All of this makes the peaceful tranquility of his poem Sensation remarkable. It’s very short, just eight lines, so here it is in full.

Portrait of Arthur Rimbaud by Étienne Carjat. Public domain

Par les soirs bleus d’été j’irai dans les sentiers,

Picoté par les blés, fouler l’herbe menue:

Rêveur, j’en sentirai la fraîcheur à mes pieds.

Je laisserai le vent baigner ma tête nue.

Je ne parlerai pas ; je ne penserai rien.

Mais l’amour infini me montera dans l’âme ;

Et j’irai loin, bien loin, comme un bohémien

Par la Nature, heureux comme avec une femme.

On the blue evenings of summer, I will walk the paths,

Pricked by wheat, treading the fine grass

A dreamer, I’ll feel the freshness at my feet,

And let the wind bathe my bare head.

I will not speak; I will think of nothing.

But infinite love will rise in my soul;

And I will go far, very far, like a gypsy

Through nature, as happy as if with a woman.

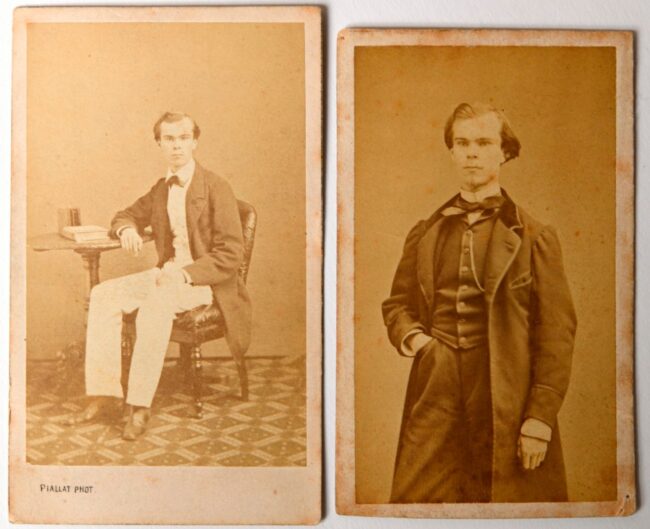

Photographs of a young Paul Verlaine, between 1860 and 1870. Public domain

Paul Verlaine (1844-1896) was, said Patrick Hamel, a “master of musicality.” Again, much of his poetry belies an unsettled life. For example, he left his wife and young child for a stormy relationship with the younger poet Rimbaud and was eventually imprisoned for shooting him in furious anger. Despite this and the drunkenness and debauchery of his later years, critics describe many of his lyrical poems as so beautiful that they are “rarely surpassed in French literature.” Vert (Green) is a good example.

Voici des fruits, des fleurs, des feuilles et des branches.

Et puis voici mon cœur, qui ne bat que pour vous.

Ne le déchirez pas avec vos deux mains blanches

Et qu’à vos yeux si beaux l’humble présent soit doux.

J’arrive tout couvert encore de rosée

Que le vent du matin vient glacer à mon front.

Souffrez que ma fatigue, à vos pieds reposée,

Rêve des chers instants qui la délasseront.

Sur votre jeune sein laissez rouler ma tête

Toute sonore encore de vos derniers baisers;

Laissez-la s’apaiser de la bonne tempête,

Et que je dorme un peu puisque vous reposez.

Here is fruit, here are flowers, branches and leaves.

And here too is my heart, which beats only for you.

Do not tear it apart with your two white hands,

May my small gift seem sweet in your lovely eyes.

I arrive still drenched in dew

Which the morning breeze freezes on my brow.

Allow me, in my fatigue, to lie at your feet,

And dream of sweet moments to relax me,

Let me rest my head against your sweet young breast

Still recalling your last kisses;

Let it be calmed after the great storm,

Let me sleep a little, for you are resting.

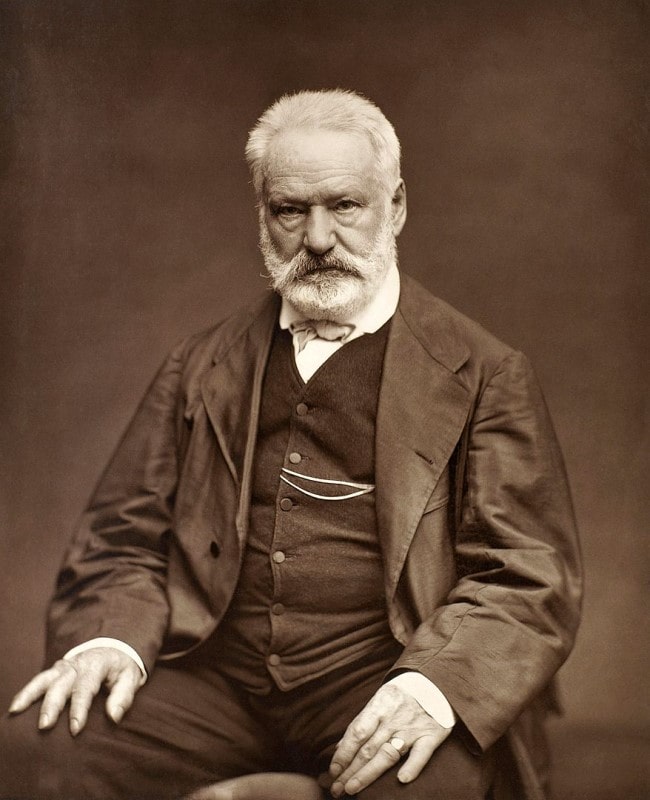

Victor Hugo (1802–1885) is best known in the English-speaking world as a novelist, the author of The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Les Misérables, yet in France he is revered above all as a poet. He was prolific, said to have written either 100 lines of verse or 20 pages of prose every morning and has been described as “the most powerful mind of the Romantic movement.” As a member of both the Académie Française and the Assemblée Nationale he became an elder statesman and when he died in his 80s, well over a million people lined the streets for his funeral.

One of Victor Hugo’s best-known poems is the poignant Demain dès l’Aube (Tomorrow at Dawn), written four years after the greatest personal tragedy of his life, the accidental drowning of his newly-married, pregnant daughter Léopoldine.

Victor Hugo by Étienne Carjat. Public Domain

Demain, dès l’aube, à l’heure où blanchit la campagne,

Je partirai. Vois-tu, je sais que tu m’attends.

J’irai par la forêt, j’irai par la montagne.

Je ne puis demeurer loin de toi plus longtemps.

Je marcherai les yeux fixés sur mes pensées,

Sans rien voir au dehors, sans entendre aucun bruit,

Seul, inconnu, le dos courbé, les mains croisées,

Triste, et le jour pour moi sera comme la nuit.

Je ne regarderai ni l’or du soir qui tombe,

Ni les voiles au loin descendant vers Harfleur,

Et, quand j’arriverai, je mettrai sur ta tombe

Un bouquet de houx vert et de bruyère en fleur.

Tomorrow, at dawn, just as the countryside turns pale,

I will go. You see, I know that you are waiting for me.

I will go through the forest, I will go over the mountains.

I cannot stay away from you any longer.

I will walk with my eyes fixed on my thoughts,

Without seeing anything else, without hearing a sound,

Alone, unknown, back hunched, hands crossed,

Sad, and for me day will be as night.

I will watch neither the gold of evening falling,

Nor the faraway sails coming into Harfleur.

And when I arrive, I will place on your grave

A bouquet of green holly and of heather in bloom.

Auguste de Chatillon (1813-1881). “Léopoldine au Livre d’heures”. Huile sur toile, 1835. Paris, Maison de Victor Hugo.

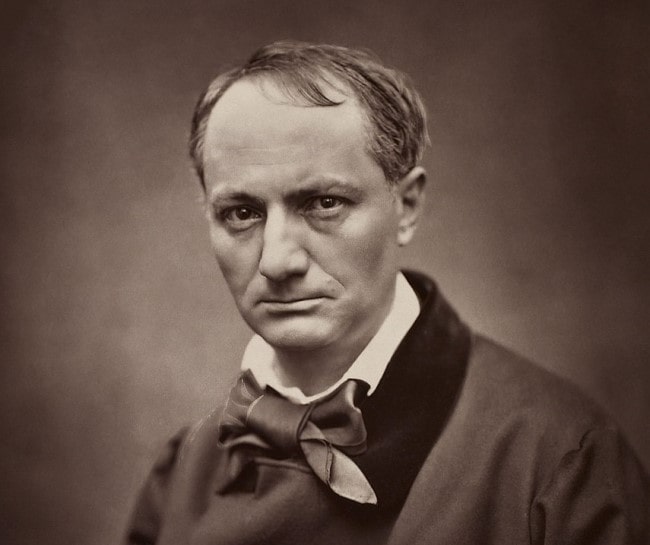

Charles Baudelaire (1827-1867) is best known for Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil), often described as the 19th century’s most influential poetry collection. Its themes range from art and beauty to romantic and sexual love, and the poems are full of sensual imagery, much of it influenced by his travels to distant lands such as India and Mauritius. It created an immediate scandal, deemed an offense against religion and public morality, and a trial was held at which some poems were banned and Baudelaire was fined. Depressed and in financial difficulties, he died at only 46, unaware that the next generation of poets would idolize him and that Les Fleurs du Mal would remain a bestseller into the 21st century.

The opening lines of Harmonie du Soir (Evening Harmony), from Les Fleurs du Mal, are a good example of the sensuous language for which the collection is well-known.

Voici venir les temps où vibrant sur sa tige

Chaque fleur s’évapore ainsi qu’un encensoir;

Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir;

Valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige!

Chaque fleur s’évapore ainsi qu’un encensoir;

Le violon frémit comme un coeur qu’on afflige;

Valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige!

Le ciel est triste et beau comme un grand reposoir.

Here comes the season when, swaying on its stem,

Every flower is perfumed like a censer;

Sounds and perfumes float in the evening air;

Melancholy waltz and languid vertigo!

Every flower is perfumed like a censer;

The violin quivers like a tormented heart;

Melancholy waltz and languorous vertigo!

The sky is sad and beautiful like a vast altar.

Charles Baudelaire by Étienne Carjat, 1861. Public domain

Louis Aragon (1897-1982) was both a surrealist poet and a communist activist. Patrick Hamel ended his Voyage dans la Poésie with a recital of Aragon’s Strophes pour se souvenir (Verses for Remembrance), written in honor of 23 activists shot by the Nazis in 1944 for carrying our bombings and assassinations. They were émigrés in France, led by an Armenian refugee, Missak Manouchian, who is recognized today as a hero of the French Resistance and is buried in the Panthéon.

Aragon pays tribute to the fallen heroes “whose names are difficult to pronounce” and yet who were “morts pour la France’” (‘had died for France’). He recalls the brutality of their execution on a cold February morning and ends the poem with a moving adaptation of words from the last letter which Manouchian wrote to his wife. Here are the last few lines:

Que la nature est belle et que le coeur me fend

La justice viendra sur nos pas triomphants

Ma Mélinée ô mon amour mon orpheline

Et je te dis de vivre et d’avoir un enfant

Ils étaient vingt et trois quand les fusils fleurirent

Vingt et trois qui donnaient leur cœur avant le temps

Vingt et trois étrangers et nos frères pourtant

Vingt et trois amoureux de vivre à en mourir

Vingt et trois qui criaient la France en s’abattant.

How beautiful is nature, and how my heart breaks;

Justice will follow upon our triumphant steps

My Melinée, oh my love, my orphan girl,

I tell you to live and to have a child.

They were twenty-three when the gun barrels opened,

Twenty-three who gave their hearts before their time,

Twenty-three foreigners and yet our brothers,

Twenty-three who loved life to death;

Twenty-three who cried out “La France” as they were struck down.

Picasso. “Apollinaire in Picasso’s Studio at 11, boulevard de Clichy, fall 1910.” Enlarged through photographing for a new negative by Dora Maar, circa 1937-1940, silver-gelatin print, 23.7 × 17.9 cm. Paris, Musée national Picasso. ©Session Picasso.

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918) was part of the avant-garde movement which took root in Paris in the early 1900s. The poems in his collection Alcools experimented with new forms, including a lack of punctuation, just as Picasso, whom he knew, was breaking the “rules” in painting. After two years fighting for France in World War I, Apollinaire was wounded and discharged. Many of the poems he went on to write continued his experimental approach but were dominated by images of war. He died in 1918 of Spanish Flu.

Apollinaire’s Le Pont Mirabeau (The Mirabeau Bridge), written in 1912, surely one of the loveliest poems set in Paris, links the flowing of the water in the Seine with the ebb and flow of human emotions. It opens as the author looks down at the water whose movements remind him that joy is always followed by pain. It ends like this:

Que vienne la nuit, que sonnent les heures

Les jours s’en vont, je demeure

Les jours passent, les semaines passent

Ni le temps passé

Ni l’amour ne reviennent.

Sous le pont Mirabeau coule la Seine

Let night come, let the bells ring

The days go by, yet I remain

The days pass, the weeks pass

Neither past time

Nor love will come back.

Under the Mirabeau Bridge flows the Seine

Le Pont Mirabeau during a Seine flood, 2018. Photo: Ibex73 / Wikimedia commons

Lead photo credit : Printemps des Poètes 2025

More in poetry, Printemps des Poètes