Something in the Air: Après Mai Le Déluge (of Nostalgia)

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

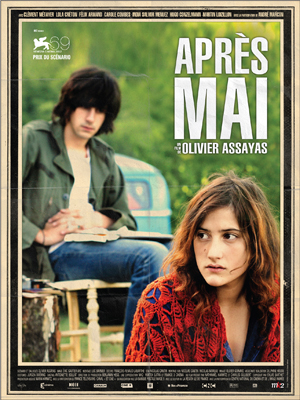

Olivier Assayas’ Après Mai (Something in the Air) tries to be not just a drama of French youth unable to let go of their ideals after May ’68, but an epic of political, social, sexual and cultural revolution. He aims at the romantic fervor of Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1900, while confining the action to the early 70s, but the effect is flat. One young woman in the audience, looking startlingly like the film’s female lead, walked out at the ¾ mark. Yet the film is technically well-made, shot with vibrant colors, and affectingly acted by the young stars Clément Métayer and Lola Creton.

Olivier Assayas’ Après Mai (Something in the Air) tries to be not just a drama of French youth unable to let go of their ideals after May ’68, but an epic of political, social, sexual and cultural revolution. He aims at the romantic fervor of Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1900, while confining the action to the early 70s, but the effect is flat. One young woman in the audience, looking startlingly like the film’s female lead, walked out at the ¾ mark. Yet the film is technically well-made, shot with vibrant colors, and affectingly acted by the young stars Clément Métayer and Lola Creton.

Gilles (Métayer) is a radical and aspiring painter. We don’t know how he became radicalized—it’s not a reaction to anything particular. Later, however, the violent beating of a militant radicalizes him further. At first he’s in love with a seductive girl named Laure (Carole Combes), who runs off to London. It’s possible this unrequited love makes him project his feelings into activism even more.

Afterwards he gets involved with Christine (Creton), who’s in a militant film collective, and becomes friends with Alain (Felix Armand), another painter. We see them in revolutionary actions, vandalizing corporate installations, producing underground newspapers, helping ultra-radical unions organize. Gilles and Christine are portrayed as radical lycéens, which might have made them too young to have participated in ’68, three years before. Perhaps the idea is to show the pathos of those who came of age too late, but this is left undeveloped.

The problem with Après Mai is that Assayas conceives the film in overly romantic terms—it’s a pastoral, not a drama. Jean-Luc Godard’s movie about Maoist militants, Les Chinoises, was very urban, but much of Après Mai is filmed in lush landscapes. Within the pastoral mood, the protagonists’ actions seem little more than youthful adventures. They don’t seem to want to go beyond that, just as the villains may beat them up, but that’s all.

Assayas captures the period with carefully chosen details. But he lingers over them—the vinyl record player, the mimeograph machine—so that they take on an unreal steampunk quality. He waxes nostalgic over the omnipresent cigarette-smoking—look, even on the train!—not realizing that his life-affirming characters are not only poisoning themselves but making money for tobacco companies.

Assayas captures the period with carefully chosen details. But he lingers over them—the vinyl record player, the mimeograph machine—so that they take on an unreal steampunk quality. He waxes nostalgic over the omnipresent cigarette-smoking—look, even on the train!—not realizing that his life-affirming characters are not only poisoning themselves but making money for tobacco companies.

What makes the film even more unreal is lack of context. There’s no mention of Vietnam, of Chile (Allende was coming to power). The Maoists never mention Nixon in China and the end of the Cultural Revolution. Post-68 was a fraught period for the French left. The Communists (not to mention the unions and Socialists) had betrayed the revolutionary students. The result was a turning towards Maoism by intellectuals and others, but Assayas doesn’t explore this. We see the protagonists helping out in a labor dispute, but it’s chiefly a Grapes of Wrath moment: mingling with the salt of the earth. On a more personal level, we don’t see any of the generational conflict at the core of ‘68.

When things get hot after an assault on a security guard, the trio move to Italy. The scenery is nice, the Italians make a refreshing change, and there’s narrative development (Alain falls for an American diplomat’s daughter). Otherwise the point of this excursion isn’t clear, and there are no allusions to the Italian autonomist movement or nihilistic Red Brigades.

The director shows Gilles’ personal development in parallel to the activism. We see him painting, but he doesn’t seem to do more than dabble. He works for a publisher who disillusions him, then for a film studio, but it’s all very summer job-ish. As incidents accumulate, we never learn much about the protagonists, and they don’t really develop, making them hard to identify with.

What redeems Après Mai (a little) are two subplots dealing with secondary characters. Alain’s American girlfriend, a sylph-like redhead with pale skin, is interested in traditional dance and takes him to Nepal. Leslie (played by India Menuez) is beguiling and a little toxic, like Jean Seburg in Breathless. She’s also genuinely poignant when she gets pregnant and decides to go alone to Holland to get an abortion.

What redeems Après Mai (a little) are two subplots dealing with secondary characters. Alain’s American girlfriend, a sylph-like redhead with pale skin, is interested in traditional dance and takes him to Nepal. Leslie (played by India Menuez) is beguiling and a little toxic, like Jean Seburg in Breathless. She’s also genuinely poignant when she gets pregnant and decides to go alone to Holland to get an abortion.

The other subplot concerns Laure. She returns in an interlude set in a country estate belonging to a wealthy patron of the radical arts. The decadent setting reminds us of the Stones’ Riviera villa while working on Exile on Main Street. This section is filmed with a grainy texture and darkly saturated colors. The scene is Dionysian, with carousing, drugs, roaring bonfires in the gardens. Gilles is turned off—Laure is meant to be like Forest Gump’s girlfriend-gone-bad. But the decadent sequences have more life than other parts of the movie, and Carole Combe, with her inarticulate mumbling, has the emotional resonance of a young Brando. A newcomer to film, she nonetheless seems like the most talented actor in Après Mai. She appears to succumb to fire when the villa burns down, but at the end of the movie Gilles dreams of an idyllic reunion with her. I don’t know about him, but as for Laure, she’s better off in the flames.

Production: MK2 Productions

Distribution: MK2 Diffusion (France), IFC Films, Sundance Selects (US)

More in Après Mai, film review, french cinema, French film